The summer before the sarin gas attack on the Tokyo subway in 1995, a similar incident had taken place in the small town of Matsumoto, Nagano. A panicked provincial police force quickly homed in on the man who had first reported that something was wrong as the likely culprit, though he was later proved innocent when, following the subway attack, Aum Shinrikyo claimed responsibility for the trial run in Matsumoto revealing that they intended to test out the gas while killing a series of local prosecutors they assumed were about to rule against them in a land dispute raised by townspeople who objected to the cult’s intention to set up a new branch in the area.

Kei Kumai’s films had often dealt with difficult subjects and particularly with those who suffered under a false accusation, but Darkness in the Light (日本の黒い夏ー冤罪, Nippon no Kuroi Natsu – Enzai) was also personal to him as he knew the man concerned, Kono renamed for the film as Kanbe (Akira Terao), and found it absurd that such an ordinary person could have planned and carried out a deadly chemical attack literally in his own back yard. Essentially putting both mass media and the police force on trial, he frames the tale through the eyes of two earnest high school students who are making a documentary about the way Kanbe was treated for their high school film club.

The obvious point is that if the Matsumoto police force, which the film claims had become aware that Aum possessed sarin gas, had conducted a better investigation then there is the possibility that the subway attack might have been prevented. The teens want to know what went wrong and how an ordinary citizen can suddenly be made public enemy number one overnight with no physical evidence linking him to the crime. What they discover through interviewing the only local TV news outlet that did attempt to conduct an investigation and contradict the reports being issued by the police, is a dangerous collusion between police and media that is supported by the business interests that underpin the news industry. Most outlets simply print press releases or unofficial leaks from the police without fact checking them. Sasano (Kiichi Nakai), the TV station editor, no longer does this because a previous false report implicating a teenage boy in a murder he had not committed had resulted in his suicide.

Nevertheless, his junior associate, Koji (Yukiya Kitamura), has his mind less on the truth than the scoop. He thinks they should publish the information they get as quickly as possible otherwise other outlets will publish first. Koji is also the most certain that Kanbe is guilty, believing they are being overcautious in their reporting and will pay for it later. The station’s managers and sponsor committee feel much the same, directly telling Sasano that he should refrain from creating his own news and instead publish what everyone else publishes. They also imply that public opinion has now in a sense become “the truth” and his reporting should be in line with it, rather than the other way around with responsible media as an arbitrator of objective facts which have been thoroughly researched and confirmed.

Sasano airs an alternative view but admits he does so more in the interest of ratings than he does for truth or justice realising that there is some currency in going against the grain and that if Kanbe turns out to be innocent after all they will come out of it much better than everyone else who published the police press releases unquestioningly. Even so, they too become subjects of harassment with relentless calls from locals decrying their irresponsible attempt to undermine the police and let a mass killer go free. Despite the care they had taken in investigating the information presented to them, they too had broadcast falsehoods such as the “expert” testimony that any old fool could make sarin gas by chucking some stuff in a bucket and standing back, only learning later from a university professor that it requires a high level of chemical knowledge, specialist equipment, and professional protective gear not available to a man like Kanbe who did have various chemicals in his home but only the kind easy to buy for use in harmless hobbies such as photography and ceramics.

Even they have cultivated close relationships with people in the police who feed them information on investigations, Sasano having a personal connection with the officer in charge of the case, Yoshida (Renji Ishibashi). Appearing somewhat conflicted, Yoshida faces pressure from his superiors to pin the case on Kanbe despite beginning to believe he is likely innocent not least because he does not give in to their pressure tactics and confess. Kanbe asks to be allowed to speak to witnesses who have supposedly given the police information on him, as if aware the police may simply be making things up to prod him into confessing while they otherwise break an agreement to restrict interviews to two hours given that Kanbe was also injured in the gas attack and is in poor health. His original reluctance to talk to the police because he was seriously ill and incapable of answering their questions seems to have annoyed Yoshida and given him the impression he must be hiding something as does his sensible decision to consult a lawyer. As Kanbe is interviewed as a “witness” rather than a “suspect” his lawyer is not present in the room allowing police to get away with what is quite clearly an abuse of their power.

Sasano points out that an Olympic ski event was also taking place nearby so the police were keen to keep the investigation under wraps, while their later reluctance to change tack when Kanbe refused to confess is nothing more than an attempt to protect their reputation fearing that they would look foolish in the press for having painted Kanbe as the villain when he wasn’t. Their plan was to arrest Kanbe anyway and suggest that he was involved with the cult while acknowledging that they had planned the attack to end the land dispute. Kanbe becomes a hapless victim of circumstance, an everyman misused by an authoritarian institution trying to maintain its own grip on power rather than fulfilling its responsibility to keep the people safe by ensuring the real culprits were prevented from committing further crimes.

Kumai comes in hard for mass media, exposing the network that sees local information bounced back through Tokyo head offices, the collusion between police and the press that leaves reporters unwilling to rock the boat for fear of losing access, and a general indifference for the welfare of individuals caught up in the real events they report on. Despite the youthful eyes of his protagonists whose untainted idealism gives the newspaper men pause for thought, a slightly dated approach displays little of the intensity or visual flair present in some of Kumai’s earlier work while falling back on sentimental cherry blossom imagery if offering a poignant opportunity for reflection on a system in urgent need of repair as Kanbe prepares to go on with his life leaving the past far behind him.

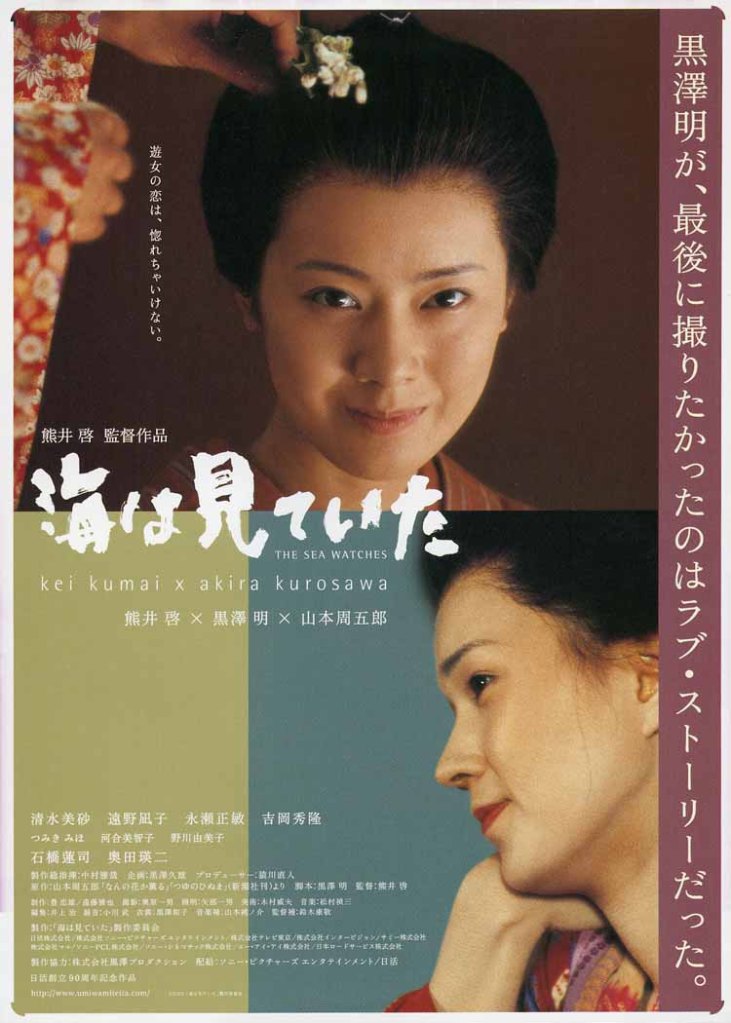

Akira Kurosawa’s later career was marred by personal crises related to his inability to obtain the kind of recognition for his films he’d been used to in his heyday during the golden age of Japanese cinema. His greatest dream was to die on the set, but after suffering a nasty accident in 1995 he was no longer able to realise his ambition of directing again. However, shortly after he died, the idea was floated of filming some of the scripts Kurosawa had written but never proceed with to the production stage including The Sea is Watching (海は見ていた, Umi wa Miteita) which he wrote in 1993. Based on a couple of short stories by Shugoro Yamamoto, The Sea is Watching would have been quite an interesting entry in Kurosawa’s back catalogue as it’s a rare female led story focussing on the lives of two geisha in Edo era Japan.

Akira Kurosawa’s later career was marred by personal crises related to his inability to obtain the kind of recognition for his films he’d been used to in his heyday during the golden age of Japanese cinema. His greatest dream was to die on the set, but after suffering a nasty accident in 1995 he was no longer able to realise his ambition of directing again. However, shortly after he died, the idea was floated of filming some of the scripts Kurosawa had written but never proceed with to the production stage including The Sea is Watching (海は見ていた, Umi wa Miteita) which he wrote in 1993. Based on a couple of short stories by Shugoro Yamamoto, The Sea is Watching would have been quite an interesting entry in Kurosawa’s back catalogue as it’s a rare female led story focussing on the lives of two geisha in Edo era Japan.