A traumatised woman overcomes her sense of loneliness by sharing her life with a limbless inflatable doll in the aptly named Torso (トルソ). More than a treatise on urban disconnection, the directorial debut from Yutaka Yamazaki is both an exploration of the lingering effects of childhood trauma and a contemplation of contemporary womanhood, the changing relationship dynamics between men and women, and the extent of bodily autonomy in an often conformist society while ending on a note of ambiguity which may represent either liberation or resignation.

34-year-old Hiroko (Makiko Watanabe) works at an apparel studio where she is among the older of the employees and somewhat aloof with her colleagues, declining invitations to hang out after work or attend the singles mixers one of the other girls is forever organising. She is indeed the sort of person who likes to keep her distance, ostensibly preferring her own company spending her time working on a patchwork quilt but secretly cuddling up at night with a slightly smaller than life-size inflatable male torso which is anatomically correct yet has no head, arms, or legs and into which she must herself breathe life only to let it out again later. Her only other real connection is with her younger half-sister Mina (Sakura Ando) who is her polar opposite in terms of personality, a bubbly, energetic woman who seems to crave the kind of contact her sister is largely unable to give her.

Even so despite claiming to hate having other people in her space, Hiroko is indulgent of Mina always giving in and allowing her to stay at her apartment at one point for an extended period of time even if not entirely happy about it. While Hiroko has eschewed male contact for the 100% controllable union with the torso pillow, Mina is trapped in an abusive relationship with a man, the otherwise unseen Jiro, whom we later learn to have been a long term boyfriend of Hiroko. Theirs is a relationship frustrated and defined by unresolved resentments, Hiroko complaining that Mina always takes everything she treasures beginning it seems with her mother’s love. A colleague of Hiroko’s around her own age laments that at their age weddings and funerals are the only occasions that they visit their hometowns, but Hiroko is reluctant to visit for reasons other than the usual awkwardness between grownup children and their parents, dressing up and catching a train to attend the funeral of the stepfather we gather must have abused her while her mother (Miyako Yamaguchi) turned a blind eye but finally unable to go through with it.

For Hiroko’s mother, Hiroko is the embodiment of her resentment towards her first husband who left her, later on another visit snapping back that she must have got her “unpleasant personality” from him while otherwise praising Mina who admittedly has bad taste in men but a generous heart. Hiroko meanwhile projects her own resentment onto her mother who failed to protect her from abuse she wonders possibly because of the resentment she feels towards her while she also projects her feelings of jealous inadequacy onto Mina who may also in a sense resent her for being unable to return the sisterly affection she desires. As she replies, she took Hiroko’s things because she only wanted her love even if vicariously through the otherwise abusive relationship with Jiro whose child she is also carrying.

In many ways it’s Mina’s pregnancy which forces Hiroko to reassess her life, not least in the accusation that she had wanted to carry Jiro’s child herself. At 34 Hiroko is perhaps at a moment of crisis, her frosty mother coldly telling her she’ll soon have to “give in” and abandon her solitary life for a conventional marriage (despite her recent widowhood her mother has already started another affair with the guy from the funeral parlour). On the other hand, are men actually very necessary anymore or has true independence become not only viable but a respected choice? Despite the constant mixers, some of the younger women at the office have decided not to wait for marriage and have already put a foot on the property ladder getting a good deal on a mortgage by starting young to own their own place and achieve financial independence. “You can’t rely on men these days” one of others agrees while recognising that choosing this kind of independence does not necessarily mean a rejection of romance or long term relationships.

For her part, Hiroko is wary of men who do in the main seem to be sleazy and predatory, visibly flinching as an over-friendly clerk at the car rental office repeatedly attempts to lean across her while she’s sitting in the driving seat. Aside from its obvious insentience, the torso is symbolically unable to harm her in having no arms to strike, no legs to kick, and no head to hurt while preserving the part she most craves buried in its empty chest which she cradles constantly like a child with a favourite toy. Her attachment to it is not purely physical but emotional, taking it on a mini holiday to the beach dressed in a pair of tiny speedos as they frolic in the sea together alone on a private beach. Yet even this body as empty as she feels her own to be can also betray and be betrayed, another treasure to be stolen if only in the breaking of a spell on realising that Mina has discovered her secret.

Mina’s final decision is both old-fashioned and ultra-contemporary, vowing to go back to the country and raise the child alone while in a symbolic sense becoming her mother in intending to take over her old part-time job at a nursing home. Hiroko meanwhile is preoccupied with the idea that she’s sacrificing her dreams and aspirations because of something that’s essentially Jiro’s fault, in part stripping her of her own agency in making her decisions and imposing on her the view that struggling in the city even if it doesn’t really suit you is inherently better than making a simple life at home. A brassy gravure model (Sora Aoi) who makes a point of the fact her body is business similarly looks down on Mina, suggesting that she’s simply weak and if she really wanted to pursue her dreams she’d have an abortion without a second thought. Yet does it really need to be an either or? The decision that Hiroko finally comes to may suggest that it might, or then again perhaps she’s merely freeing herself of her long held trauma and looking to lead a more emotionally fulfilling life. “We’re just starting out” Mina shouts back from from across the ticket barriers as she leaves hinting at new beginnings for each of the sisters having each at least laid something to rest.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

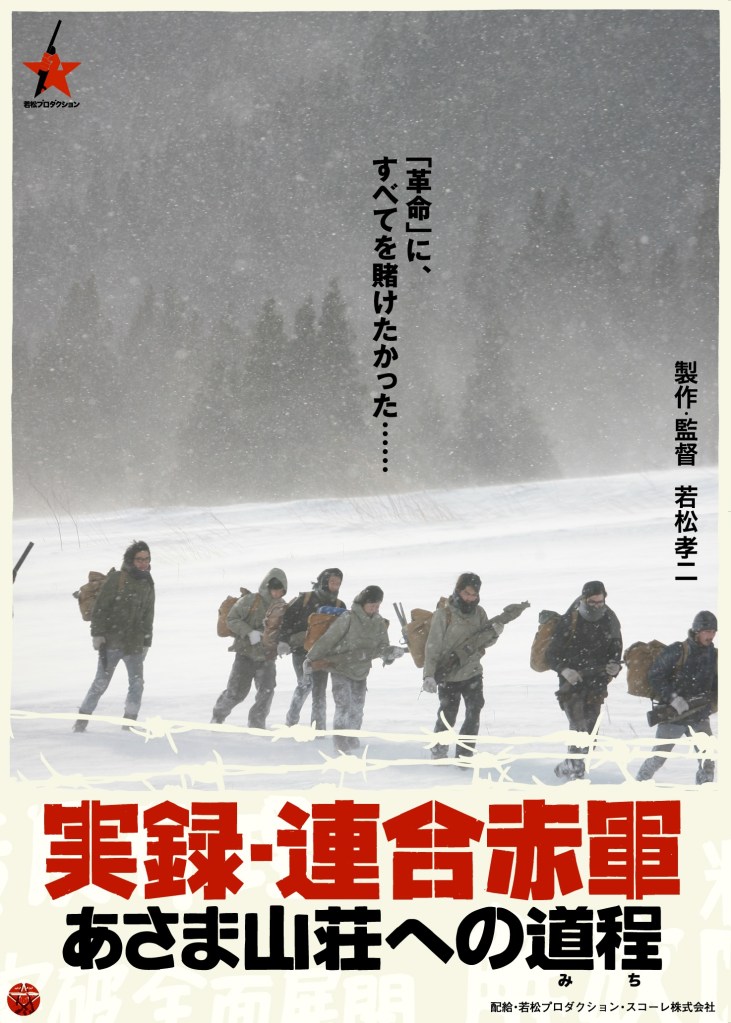

Koji Wakamtasu had a long and somewhat strange career, untimely ended by his death in a road traffic accident at the age of 76 with projects still in the pipeline destined never to be finished. 2008’s United Red Army (実録・連合赤軍 あさま山荘への道程, Jitsuroku Rengosekigun Asama-Sanso e no Michi) was far from his final film either in conception or actuality, but it does serve as a fitting epitaph for his oeuvre in its unflinching determination to tell the sad story of Japan’s leftist protest movement. Having been a member of the movement himself (though the extent to which he participated directly is unclear), Wakamatsu was perfectly placed to offer a subjective view of the scene, why and how it developed as it did and took the route it went on to take. This is not a story of revolution frustrated by the inevitability of defeat, there is no romance here – only the tragedy of young lives cut short by a war every bit as pointless as the one which they claimed to be in protest of. Young men and women who only wanted to create a better, fairer world found themselves indoctrinated into a fundamentalist political cult, misused by power hungry ideologues whose sole aims amounted to a war on their own souls, and finally martyred in an ongoing campaign of senseless death and violence.

Koji Wakamtasu had a long and somewhat strange career, untimely ended by his death in a road traffic accident at the age of 76 with projects still in the pipeline destined never to be finished. 2008’s United Red Army (実録・連合赤軍 あさま山荘への道程, Jitsuroku Rengosekigun Asama-Sanso e no Michi) was far from his final film either in conception or actuality, but it does serve as a fitting epitaph for his oeuvre in its unflinching determination to tell the sad story of Japan’s leftist protest movement. Having been a member of the movement himself (though the extent to which he participated directly is unclear), Wakamatsu was perfectly placed to offer a subjective view of the scene, why and how it developed as it did and took the route it went on to take. This is not a story of revolution frustrated by the inevitability of defeat, there is no romance here – only the tragedy of young lives cut short by a war every bit as pointless as the one which they claimed to be in protest of. Young men and women who only wanted to create a better, fairer world found themselves indoctrinated into a fundamentalist political cult, misused by power hungry ideologues whose sole aims amounted to a war on their own souls, and finally martyred in an ongoing campaign of senseless death and violence.