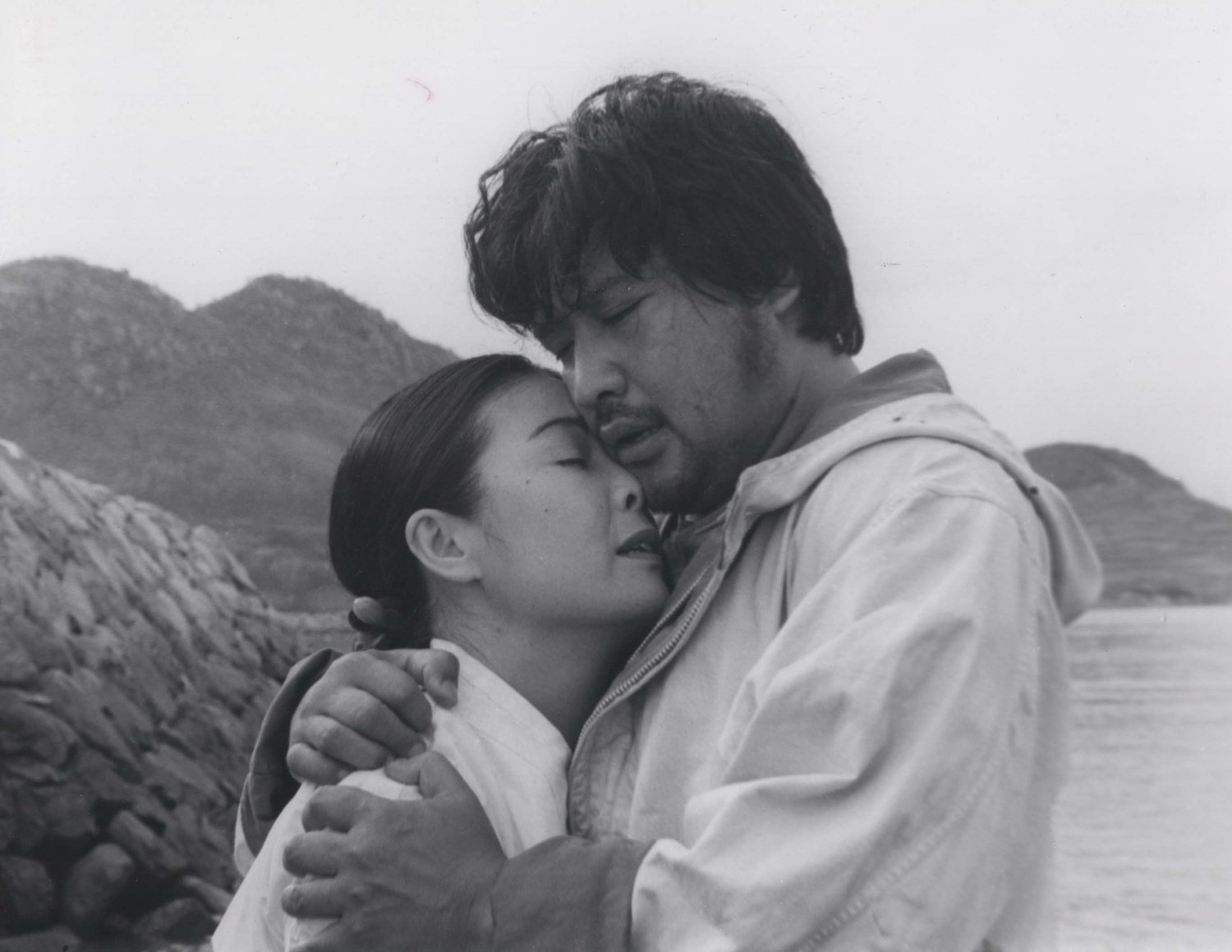

“From now on we need think only of our children. We can’t pass on shamanism to them. Our children at least should have a bright future” insists a man whose horizons have in one sense been broadened but perhaps in another narrowed following forced immersion in the modern world. A classic “island” film, Im Kwon-taek’s Divine Bow (神弓 / 신궁, Singung) finds a conflicted modern day shamaness reassessing her place in a community which has systemically betrayed her while trying to find a path through the intensity of her grief and sorrow.

Set almost entirely on the small fishing island of Naro, the film opens with a series of short, static shots of the rainy harbour where an old man sits and strokes his beard wearing traditional Korean dress while a group of seemingly unemployed young men look on listlessly from the boats. It seems the community is in crisis for a number of reasons, the most pressing being a non-existent harvest of fish which they are choosing to attribute to the local shamaness’ refusal to perform the customary rituals. Unmoved by their petitioning, Wangnyeon (Yoon Jeong-hee) advises them to hire her daughter-in-law instead, but for unexplained reasons they only want her, threatening to hire a shaman from a neighbouring island if she continues her policy of non-cooperation. As we will discover, Wangnyeon has her reasons beyond a simple desire for retirement from what is a fairly strenuous job for an ageing woman, but the return of her long absent son Yongban prompts her into a reconsideration of her past and future as well as her place in this community.

Though the tale is set in the present day, the fishermen are convinced that Wangnyeon’s refusal to conduct the ritual is the reason their harvest has failed, apparently for the first time in 30 years ever since she “retired”. But then they also tell us themselves of more rational reasons they may no longer be able to fish including an oil leak in the surrounding seas and the corrupting influence of larger corporations for which many of them are now reluctantly working. It is precisely this incursion of modernity that has led to all the trouble. Taken off the island, presumably to fulfil his military service, Wangnyeon’s husband Oksu (Kim Hee-ra) observes the modern world during his time in the army and comes to the conclusion that his home culture is backward and superstitious. Hired to perform an important ritual on a neighbouring island for the first time, Wangneyon repeatedly delays the contract to align with her husband’s discharge so he can play drums for her as he always had before. His newfound sophisistication, however, has robbed him of the ability to play. He no longer believes in shamanism and eventually leaves once again to work on a ship in order to one day own a fishing boat of his own.

“What does a shaman do if not rituals?” Wangnyeon irritatedly asks her husband, in her case the answer apparently being a defiant nothing. Her refusal is part of her resistance to a world that has repeatedly betrayed her. Yet suffering economically temporarily loses her her son who, perhaps unlike his father, returns after a year of travelling more convinced than ever by shamanism if resentful that his mother has not yet relented and resumed her ritual duties. What we realise is that Wangnyeon has grown weary of her complicated place in the island hierarchy, existing to one side of the rest of the community who view her both with mild disdain and fearful awe. A victim of petty island politics, she takes literal aim at the corruption in her society and purifies it with her “divine bow”, mindful of Yongban’s pleas that her rituals are not just for her but for the many people who need to see them performed.

“Everything, everything, everything is a dream” Wangyeon sings, living perhaps in her own ethereal purgatory, her jagged life story revealed to us in a series of fragmentary flashbacks as she reflects on her present predicament while finally understanding what it is she must do, determining to pick up the divine bow once again and reassume her rightful role as the shamanness. Marking Im’s first collaboration with cinematographer Jung Il-sung, Divine Bow is rich with ethnographic detail exploring this small rock pool of traditional culture on an otherwise moribund island subject to the same petty authoritarian corruptions and ravages of an increasingly capitalistic society as anywhere else.

Divine Bow streams in the UK until 11th November as part of this year’s London Korean Film Festival.