Some might say, it’s best to learn the lesson that life is disappointing as early as possible but there can be few who meet encroaching old age without a sense of regret and failure. The couple at the centre of Park Ki-yong’s Old Love (재회, Jaehoe) seem to have little else as they unexpectedly reunite at differing points of reunion and abandonment, longing for an unreachable past where their youthful dreams of a happier future were still possible and they could, at least, live with a false sense of hope. All that’s left for them now is to find resignation in the remaining days of loneliness and futility.

Some might say, it’s best to learn the lesson that life is disappointing as early as possible but there can be few who meet encroaching old age without a sense of regret and failure. The couple at the centre of Park Ki-yong’s Old Love (재회, Jaehoe) seem to have little else as they unexpectedly reunite at differing points of reunion and abandonment, longing for an unreachable past where their youthful dreams of a happier future were still possible and they could, at least, live with a false sense of hope. All that’s left for them now is to find resignation in the remaining days of loneliness and futility.

Yoon-hee (Yoo Jung-ah), who has been living in Canada for the past 30 years, returns to Korea for the Lunar New Year holiday in order to confer with her remaining family members and decide what’s best for her elderly mother now suffering with dementia. Already conflicted, Yoon-hee’s homebound holiday gets off to the worst of starts when she realises her suitcase is broken and gets caught up in an inescapable cycle of airport bureaucracy. Her exit is further delayed by a brief cigarette break during which she hears a familiar voice. Jung-soo (Kim Tae-hoon), her college boyfriend, is also at the airport dropping off his 17-year-old daughter who is on her way to study abroad in Australia. Not quite knowing why, Yoon-hee calls out to him and the former lovers engage in awkward conversation, eventually swapping (temporary) phone numbers and agreeing to meet up while Yoon-hee is in the country.

Neither Yoon-hee nor Jung-soo give much indication of the nature of their college era relationship or why it eventually ended. They’ve obviously not stayed in touch, though there is relatively little animosity between them and no desire to argue about or dig up the past. Together once again they walk the no longer familiar streets, exchanging vague memories – a taste for octopus, forgotten left handedness, shops which have long since closed down. Their world has already disappeared and left them behind with only the burden of nostalgia to sustain them.

Long ago, Yoon-hee and Jung-soo were members of a theatre troupe. Jung-soo once said that theatre was more precious than life, yet at some point he gave it up. Now broken and dejected, he is a lonely widower whose daughter has abandoned him in resentment to look for her better future somewhere else. Yoon-hee left the theatre behind to go to Canada where she married, it seems mostly for convenience, and had a son who is now 27 years old and about to be married himself. Yoon-hee’s son returned to Korea but the pair are estranged and she won’t be seeing him on this visit. In fact she isn’t even invited to the wedding.

Yoon-hee and Jung-soo may be lonely and full of regret, but according to Jung-soo all but two of their former company fellows abandoned their dreams of the stage for more conventional lives. Mun-hee (Kim Moonhee) and Yong-guk were the two who stayed true, but Yong-guk is now seriously ill and will leave his family behind with no means of support. Later at an inn, Yoon-hee and Jung-soo run into another young group of actors eagerly debating The Seagull. Jung-soo can’t help butting in, a sad old man with some words for the hopeful youngsters. Increasingly drunk, he tells them to follow their dreams no matter what or else you’ll end up regretting your life choices. If you follow your dreams and it doesn’t work out, at least you can say you tried but if you sell out and that fails too what will you have then? Jung-soo has nothing and the emptiness is crushing him.

A lonely walk brings Yoon-hee straight into the present day when she blends into the candlelight protests, perhaps further recalling the tumultuous days of her own youth lived in the early days of a new democracy filled with a hope and promise that now seems to have retreated far into the distance. Caught at points of transit – airports, train stations, resort towns, neither Yoon-hee nor Jung-soo can find the strength to move forward. He asks her to stay, to find a home with him, as he should have done all those years ago but the moment is already gone and no amount of regret can ever bring it back. Broken by life’s disappointments, the failure of their dreams, and the emptiness of their loveless lives, Yoon-hee and Jung-soo remain trapped by the inertia of their times, just two lonely people for whom the train will never arrive.

Old Love was screened as part of the 2018 London Korean Film Festival.

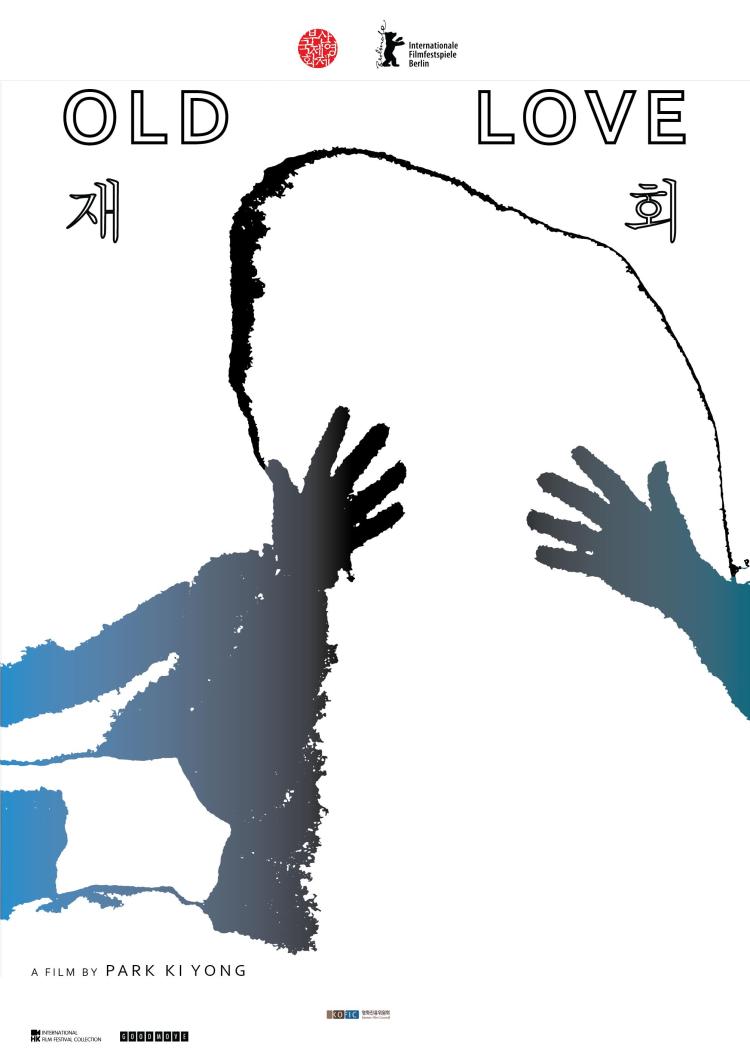

Berlinale trailer (no subtitles)