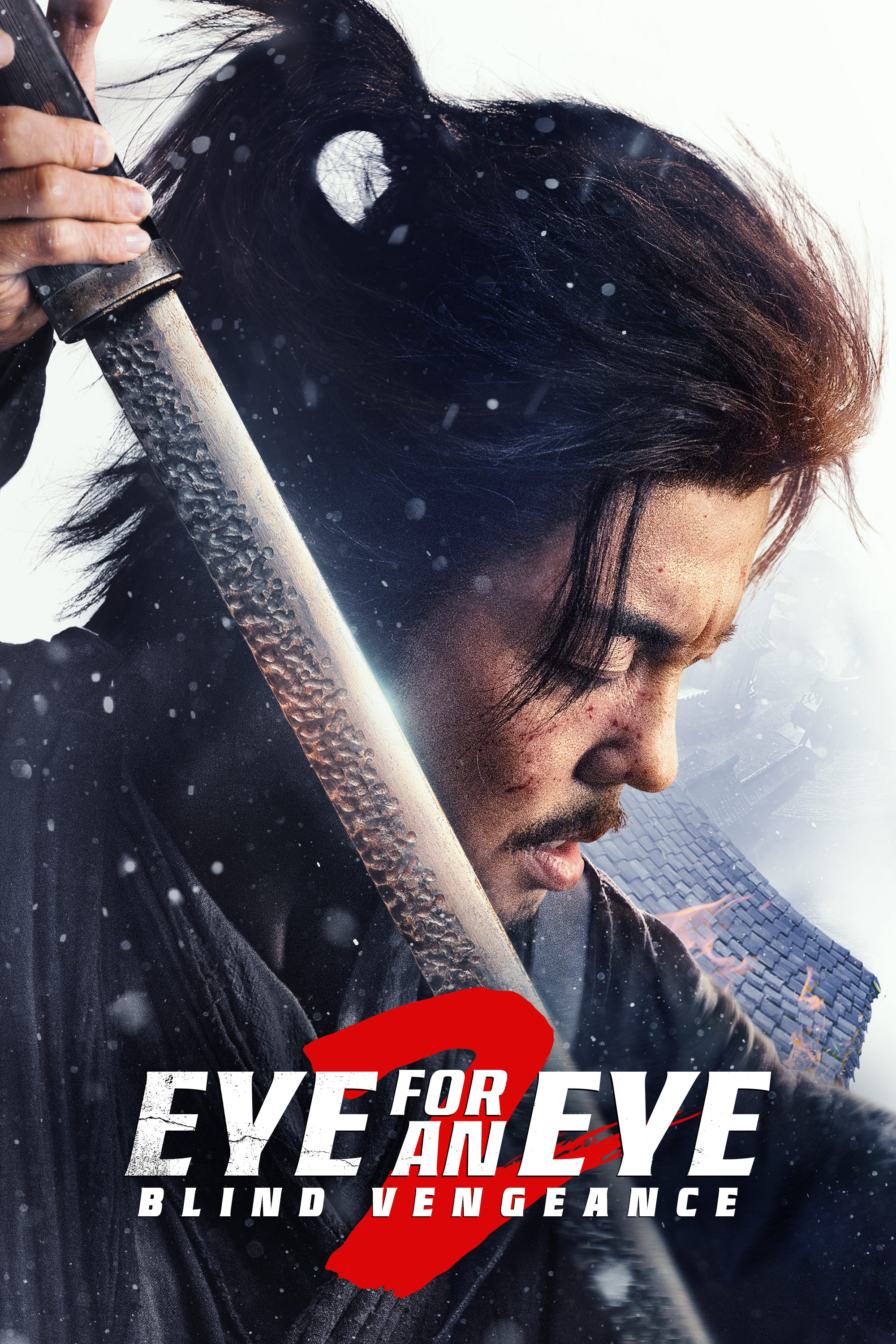

The wandering swordsman returns but this time to a world much more in disarray than when we last left it in the sequel to the surprise hit streaming movie An Eye for an Eye: The Blind Swordsman, An Eye for an Eye 2: Blind Vengeance (目中无人2, mùzhōngwúrén 2). Less origin story than endgame, the film finds bounty hunter Cheng Yi living in another dusty town and working for Youzhou Prefecture to bring in wanted criminals dead or alive but finally forced into the role of protector for a little girl dead set on vengeance against this world.

Richer in scope and ambition, this time around we’re given a little more backstory about the former lieutenant who is now using his martial skills to enact justice in an otherwise lawless society if only when he’s paid to do so. One of his targets turns out to be a man who served under him in the war and is disillusioned about its aftermath. “What did we gain in the end?” he asks, justifying himself that he may have killed a few people and taken some money but he was only claiming what he was owed. The argument doesn’t wash with Cheng Yi, but the war also took his sight from him and he too is a disillusioned exile from his home in Chang’an living a nihilistic life of drink of killing on the behalf of a distant and compromised authority.

His wilful isolation may be why he is not originally motivated to help the orphan little girl Xiaoyu (Yang Enyou) who says her mother starved to death during their escape. Xiaoyu had tried to protect her little brother who seemed to be mute only to see him trampled beneath the hooves of a debauched nobleman who had just murdered an entire family because they had dared to tell on him to his father. The family had been planning to flee at dawn but Li Jiulang (Huang Tao) got there first. Xiaoyu witnessed his crime after sneaking in to steal the bread they were baking and was then freely given to her by a young woman Li later killed, further stirring her desire for revenge. Cheng Yi ends up saving her from Li on two separate occasions, though the second time it isn’t overly clear whether it was intentional or a drunken coincidence. Nevertheless, he continues to counsel her against pursuing her revenge, especially towards a man like Li who is wealthy and connected and has no compunctions about killing children.

Li is also seen to abuse drugs and have a sadistic streak though no real explanation is given for his cruelty save that he is evil and has enough money and power to do as he pleases. No one except the little girl is going to put a bounty out on him, as she naively tries to do by selling her brother’s silver whistle to get a poster mocked up though Li simply offers a double bounty on her and it seems plenty are desperate enough to consider killing a defenceless girl to get their hands on it. Perhaps it’s this that eventually moves Cheng Yi’s heart as she continues to insist on an impossible justice even at the cost of her own life. Like him, she no longer has any family nor any place to call home and is displaced within the chaos of late Tang. Through bonding with her, he begins to rediscover his humanity and considers leaving the world of the bounty hunter behind to become an “ordinary person” in Chang’an to raise her away from this nihilistic way of life.

Building on the success of the first film, Yang Bingjia makes the most of an increased production budget to fully recreate the atmosphere of a bustling frontier town while continuing the Western influence as Cheng Yi hunts down wrongdoers in an otherwise lawless place. The connection between the cynical swordsman and his tiny charge has genuine poignancy as he continues to caution her against the path of revenge, reminding her that it is a continuous cycle and one act of vengeance merely sets another in motion, yet finally deciding that he must teach her what he knows anyway because like him she has no other way to live. Still, what he envisions for her is a peaceful life in Chang’an, far away from the chaos of the frontiers in a world that may not quite exist anymore but may yet come again if not, perhaps, for all.

Eye for an Eye 2: Blind Vengeance is released in the US on Digital, Blu-ray & DVD March 4 courtesy of Well Go USA.

Trailer (English subtitles)