The yakuza movies of the post-war era had largely depicted the gangster world as being one of internecine desperation and even if the hero was a pure-hearted defender of a traditional honour code those around him were anything but honourable. By the late 1980s, however, the yakuza were increasingly seen as an outdated institution amid the high rise office blocks of a prosperous Bubble-era Japan in which the street thug had given way to more corporatised kinds of organised crime.

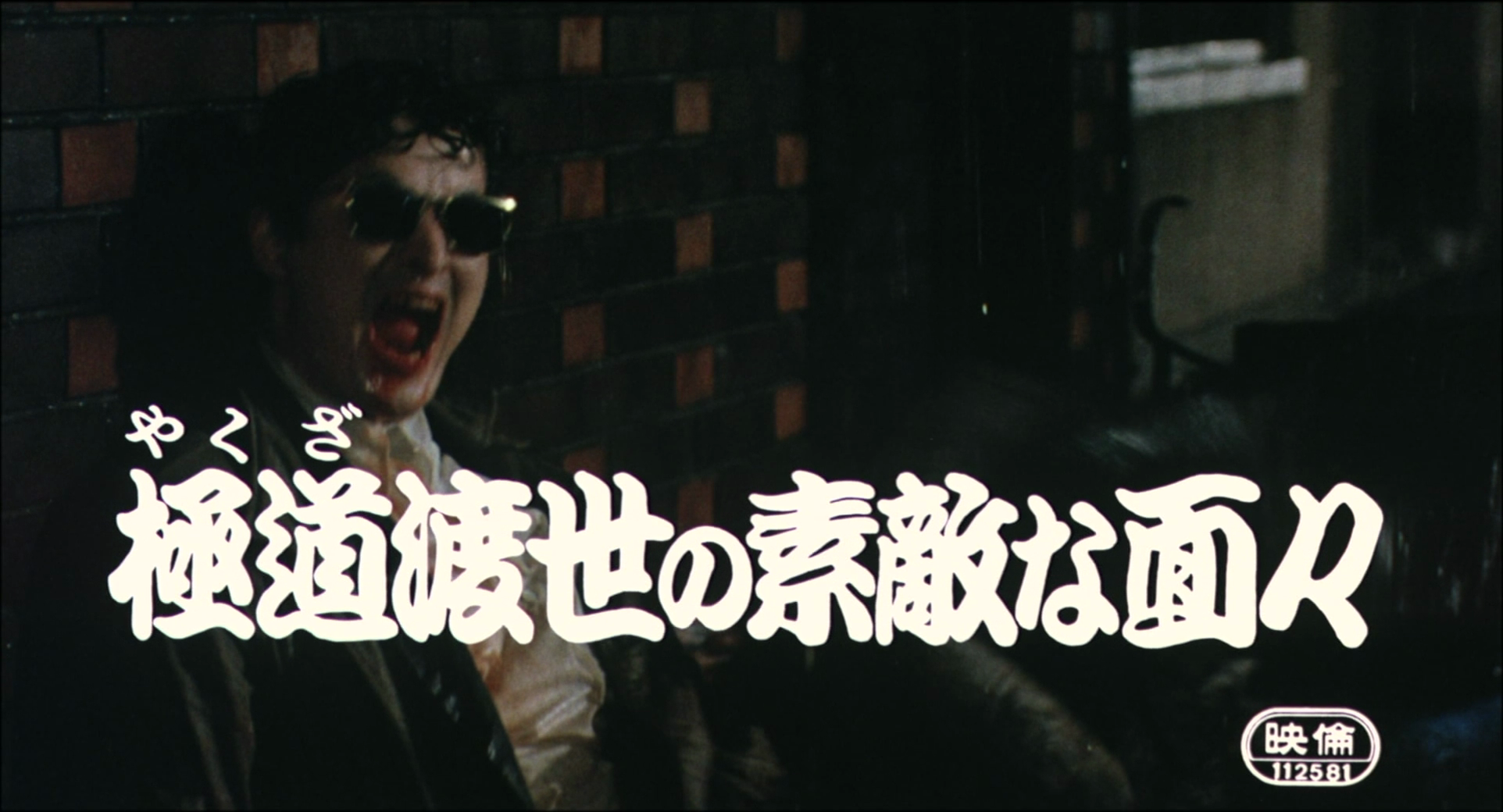

This might help to explain the ironic title of Seiji Izumi’s 1988 comedy Those Swell Yakuza (極道渡世の素敵な面々, Yakuza Tosei no Sutekina Menmen) which simultaneously presents a nostalgic view of gangster cool and a way of life which is more rooted in the everyday existence of a contemporary petty outlaw. The hero, 24-year-old Ryo (Takanori Jinnai), is a former banker who evidently rejected the heavily corporatised nature of the Bubble-era society and left his stable job to open a record store which subsequently went bankrupt leaving him with huge debts to yakuza loansharks. It’s these debts he’s trying to escape by wandering into a mahjong parlour and getting carried away with his early success despite the advice of steady hand Nakagawa (Takeshi Kusaka) who eventually covers his losses when it turns out that Ryo started playing without any stake money. A ageing yakuza, Nakagawa takes him outside to teach him a lesson explaining that the parlour is run by Taiwanese gangsters and he’s lucky to be leaving with his life. Nevertheless, Nakagawa is impressed by his hutzpah and leaves his business card in case Ryo has the desire to get in touch.

Ryo’s decision to become a yakuza reflects both a sense of emptiness in the Bubble-era society and a nostalgic longing for post-war gangsterism and the theoretical “freedom” is represents to a man like Ryo though of course there’s not so much autonomy to be had in the life of a petty footsoldier who is always beholden to the whims of his boss. Nakagawa becomes to him a kind of father figure, though he’s also someone who has largely lost out in having achieved little in the realms of gangsterdom while his friend and contemporary Kanzaki (Hideo Murota) has successfully climbed the ladder to become a high ranking officer. Kanzaki takes him to task for visiting the mahjong parlour in part because the Taiwanese gang has gained a reputation for dealing with drugs of which their organisation does not approve and it would present a problem if his connections to them were to come out during any potential anti-drug action by the police. By the film’s conclusion, Nakagawa has become something of a tragic figure more or less excluded from the yakuza world while his body is ravaged by alcoholism and his finances by gambling addiction.

Ryo, meanwhile, seems to live the yakuza dream. He gets stabbed while defending a bar hostess from a yakuza from a different gang and then meets the love of his life, Keiko (Yumi Aso), who similarly rejects the constraints of the contemporary society by refusing the marriage arranged by her father for his own benefit to spend three years waiting for Ryo who goes to prison after shooting Kanzaki in the arm to avenge a slight against Nakagawa who also cuts off his finger to fulfil the codes of yakuza honour. Wandering around in sunshades and flashy suits, Ryo soon attracts a fiercely loyal band of followers of his own and despite the tragedy of losing one of his men to an assassin proves adept in navigating the yakuza world to present an idealised image of masculine cool perfectly tailored to the Bubble era.

Despite the shooting that landed him in prison and the mission of revenge he leaves his own wedding (after the ceremony) to complete in the film’s conclusion, Ryo’s yakuza existence is otherwise fairly non-violent and based in a kind of trickery that makes him seem clever rather than exploitative given that as Nakagawa had suggested the way forward for the modern yakuza is scams not drugs. As one of his prison buddies puts it, there are old school gangsters like Ryo ready to die for the clan, and then there are those like himself intent on filling their boots. Largely, most of these guys are old school yakuza who do obey the code and have some kind of scruples about how they make their money which adds to their aspirational allure as Ryo seems to lead a fairly charmed life of idealised masculinity with a pretty wife and fancy apartment seemingly free of the petty oppressions faced by workaday salarymen. Izumi makes frequent reference to classic Toei gangster pictures from a decade previously with appearance from from genre stalwarts such as Hideo Murota, Nobuo Ando, and Mikio Narita, but lends the action a contemporary spin in the ironic sense of cool even if the implications of ambiguous ending may be far less upbeat.

The late Ken Takakura is best remembered as cinema’s original hard man but when the occasion arose he could provoke the odd tear or two just the same. 1999’s Poppoya (鉄道員) directed by frequent collaborator Yasuo Furuhata sees him once again playing the tough guy with a battered heart only this time he’s an ageing station master of a small town in deepest snow country which was once a prosperous mining village but is now a rural backwater.

The late Ken Takakura is best remembered as cinema’s original hard man but when the occasion arose he could provoke the odd tear or two just the same. 1999’s Poppoya (鉄道員) directed by frequent collaborator Yasuo Furuhata sees him once again playing the tough guy with a battered heart only this time he’s an ageing station master of a small town in deepest snow country which was once a prosperous mining village but is now a rural backwater.