No one can escape from their sins according to the ominous voiceover that opens Tatsumi Kumashiro’s loose reimagining of Nobuo Nakagawa’s Jigoku, The Inferno (地獄, Jigoku). Then again, some of these “sins” seem worse than others, so why is it that a woman must bear a heavy burden for adulterous transgression while the man who killed her seemingly suffers far less? Perhaps hell, in this case, is born of conservative social attitudes more than anything else besides the darker elements of the human heart such as jealousy and romantic humiliation.

Those negative emotions are however as old as time as reflected in the folk song which opens the film about a young couple, though not the young couple currently onscreen, who are eloping because their incestuous desire is not accepted by the world around them. The connection between the couple onscreen might also be deemed semi-incestuous for Ryuzo (Ken Nishida) has run off with the wife of his brother, Miho (Mieko Harada), who is carrying (what she claims to be) Ryuzo’s child. Unpei (Kunie Tanaka), the brother, finally catches up with them and shoots Ryuzo with a shot gun. Miho tries to escape, but her foot is caught in a bear trap and Unpei decides to leave here there to die, while Ryuzo’s jealous wife Shima (Kyoko Kishida) later does the same. The body is found by local hunters, and in a strange miracle the baby is born from Miho’s dead body while Miho is dragged to hell for her “sins” where she learns that her baby has been born in hell but remains above. Not knowing what to do, the locals give the baby, Aki, to Shima but she obviously doesn’t want it and so swaps it with a foundling thanks to a weird old man, Yamachi, coming to love this other child, Kumi, as a daughter.

This is quite literally a tale of the sins of the parents being visited on the child, the 20-year old Aki (Mieko Harada) later lamenting that she has no identity of her own and is solely a vehicle for her mother’s revenge. Though she apparently ends up in the same rural town “by chance” knowing nothing of her past, she resembles her mother physically and discovers she has some of her talents such as an innate ability to play the shamisen. What she also has is a trance-like lust that bewitches the men around her, though this is in a sense complicated by the fact it does not seem to be of her own volition so much so as a manifestation of her mother’s curse. Thus she ends up sleeping with the vulgar younger brother of the man she actually likes, Suchio, who in truly ironic fashion is actually her half-brother. She describes herself as having her mother’s “tainted blood”, while Shima later adds in a degree of class and social snobbery revealing that Miho had been a geisha Unpei unwisely fell for and was unworthy even of being a maid in their upper-middle class household let alone the wife of the second son.

For all of her resentment, Shima is otherwise a loving mother to her sons and even to Kumi whom she is able to accept as a daughter in a way she would never have accepted Aki who was after all an embodiment of her husband’s betrayal. Colder and more austere than Aki or Miho would seem to be, she clings to the mummified body of her husband kept in a secret vault as a secret triumph over her humiliation laughingly remarking that now he’s hers forever and will never cheat on her again. Even if she left Miho to die, Shima does not particularly resist her fate well aware that her son has fallen for his half-sister (which probably wouldn’t have happened if she hadn’t swapped babies) and merely hoping Aki can be convinced to leave town alone rather than plotting any more drastic action.

But the inferno of hell envelopes them all, crying out for retribution as the cycles of repressed or inappropriate attractions repeat themselves. Kumi realises that her love for her brother, Suchio, is actually not inappropriate because they are not related after all but is then consumed by her own hell in realising that he does in fact love his biological half-sister but is uncertain if he accept damnation in order to pursue it. What she, Miho, and Aki are punished for is female sexual desire aside the arguably taboo qualities of its direction though in hell it seems men are punished for this too, or more accurately for giving in to it, in a way they often aren’t in the mortal realm. “They cut their own flesh and blood for the vision of a woman in the future,” the guide explains as the brothers and Unpei literally climb over each other reaching for an illusionary representation of Aki/Miho at the top of the tree. In the mortal world they do something similar, grappling with each other, mired in competitions of masculinity as mediated through sexual dominance, conquest, or humiliation.

Yet Aki’s path to hell is also a confrontation with her femininity and her search for an identity as a woman by reuniting with the birth mother who died before she was born. Kumashiro’s visions of hell are terrifying and outlandish, a giant land in which the dead are thrown into a huge meat grinder they then have to push themselves. For the sin of eating meat, others are condemned to spend eternity eating human flesh. Miho has lost all sense of reason and is incapable of recognising her daughter seeing her only as another source of food but there is a kind of rebirth that takes place even if it’s only once again to be born in the underworld. Surreal and harrowing, Kumashiro’s eerie land of giant demons and shuffling corpses does indeed suggest that as the opening titles put it we all live our lives alongside hell.

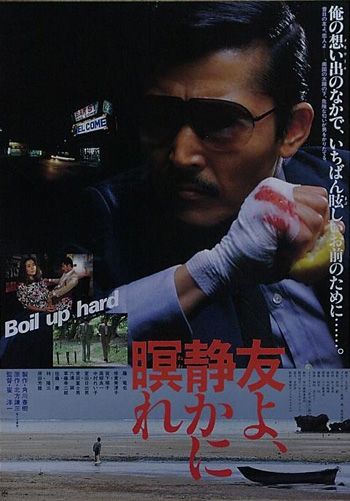

Original trailer (no subtitles)