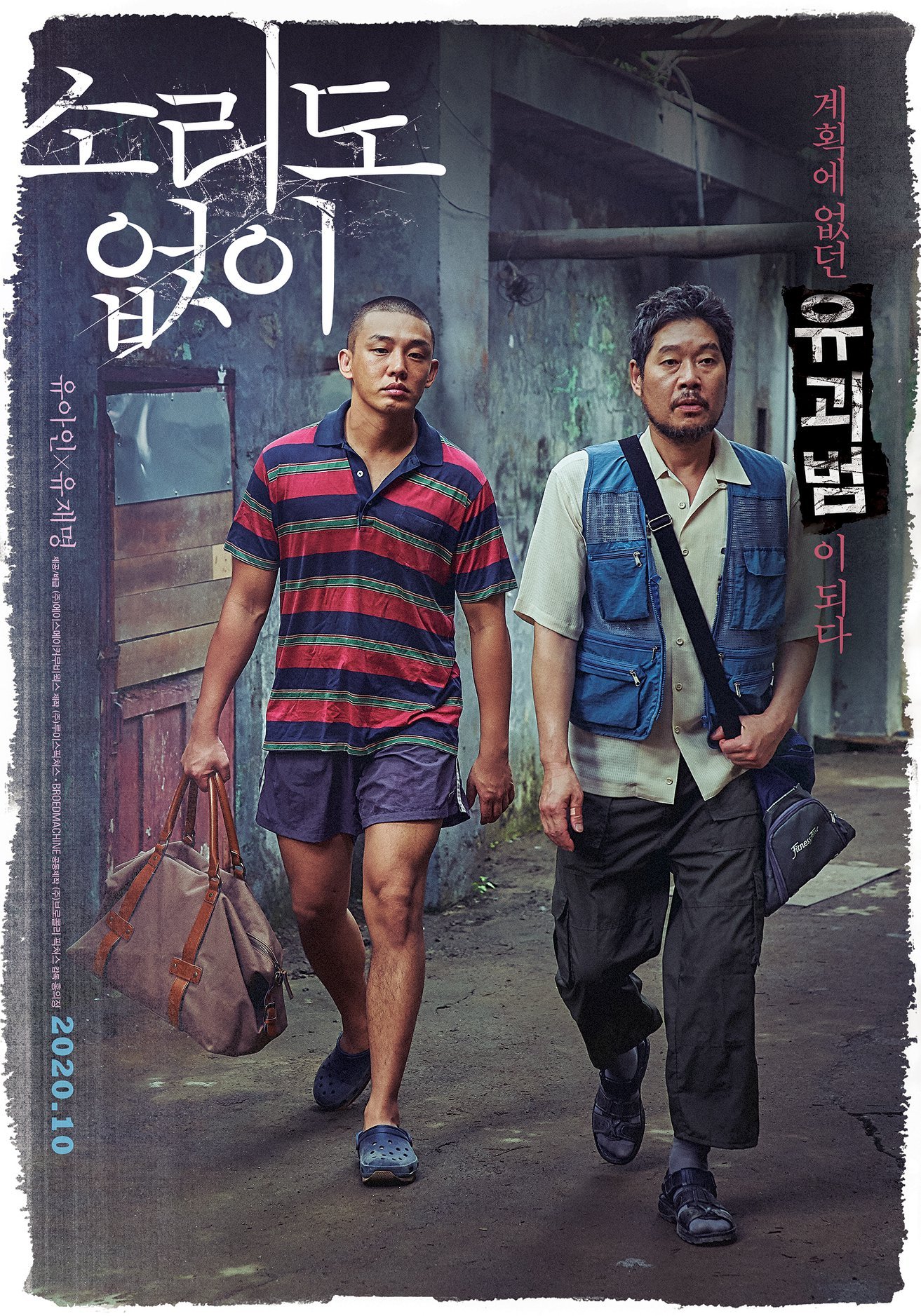

“Once you join a family, you have to pitch in, right?” the aphorism-loving protagonist of Hong Eui-jeong’s disturbingly warmhearted crime caper Voice of Silence (소리도 없이, Sorido Eopsi) explains to a little girl who has recently come into his “care” as she dutifully begins massaging the earth towards a half-buried body. Partly an exploration of the family bond and its propensity to arise even in the most duplicitous of circumstances, Hong’s ironically cheerful drama is also a mild condemnation of the modern society and its capacity to push good people to do bad things in its infinite oppressions.

Egg farmer Chang-bok (Yoo Jae-myung), for example, is a man of faith who places great stock in protestant virtues of hard work and humility. Yet he sees no irony in the sign reading “Today’s honest sweat is tomorrow’s happiness” on the wall of a disused barn where he carries out his second job preparing torture victims for gangsters and then disposing of the bodies even going so far as to say a little prayer for them, bible in hand, as he places them into shallow graves in the forest. He and his mute partner Tae-in (Yoo Ah-in) dutifully wait outside as the violence takes place, rejecting entirely their sense of complicity with the corruption of the gangster world viewing themselves only as providing a service and taking pride in providing it well.

Nevertheless, when their “manager” pays them an unexpected visit and gives them an unusual assignment of “looking after” a person for a few days they can hardly refuse even as Chang-bok reminds him it’s not in their job description. Contrary to expectation, however, the “person” turns out not to be sequestered gangster but an 11-year-old girl, Cho-hee (Moon Seung-ah), whose father is haggling over a ransom payment. When the manager is consumed by the same system he previously operated, it leaves them with a problem. They can’t simply let the girl go because the kidnappers want their cut, but the father won’t pay up and so the only other option is handing her over to child traffickers. Chang-bok and more particularly Tae-in would rather that didn’t happen, but on the other hand they aren’t really doing too much to actively prevent it.

Just as Chang-bok and and Tae-in are “egg farmers”, the child traffickers run their business out of a moribund chicken farm. The rural economy is apparently not faring so well in the modern society. Yet Hong’s countryside vistas are presented as an idyllic paradise with bluer than blue, cloudless skies and fields of verdant green. Then again those who live off the land are perhaps most aware of its compromises and of the price of survival. Chang-bok is fond of spouting vaguely religious aphorisms such as “whatever you do, do your best and be humble. Always be thankful for what you have”, later blaming his predicament on his recent laxity in attending church, but evidently sees no contradiction between his creed and way of life. He doesn’t want to hand Cho-hee over the child traffickers, but he won’t resist it either merely seeing it as an inevitable consequence of events already in play in which he is but a passive participant.

Tae-in, meanwhile, though literally voiceless is beginning to reject his passivity. Apparently raised by Chang-bok from infancy, he is currently a guardian to a mysterious “sister”, Moon-joo (Lee Ga-eun) around 15 years younger than he is though no mention is made of their parents or what might have happened to them. Charged with taking care of Cho-hee he finds himself developing a paternal fondness for her while she quite unexpectedly slides neatly into his home, bringing a strangely maternal if perhaps in its own way problematic order in tidying the place up and giving Tae-il a more concrete sense of familial rootedness. When the pair picked her up, they wondered if Cho-hee’s father was haggling over the ransom amount because the kidnappers took his daughter when they meant to take his son. Chang-bok is morally outraged, believing sons and daughters should be treated the same and shocked a father would’t immediately do everything he could to protect his little girl. But Cho-hee knows only too well that they value her brother more and in fact doubts her father will help her. She carries these old fashioned patriarchal values into Tae-in’s village home, brushing Moon-joo’s rather feral hair, teaching her to fold clothes away neatly, instructing her to speak more politely to her brother and not to start eating until he has taken his first bite.

Despite themselves, the four become an accidental family cheerfully enjoying ice lollies on a hot summer’s day trying to figure out a polaroid camera which has been bought for a slightly less happy purpose. There is perhaps an idea that Cho-hee might simply not return to her wealthy, urban family in which she feels unwanted and inferior but stay here in the more “innocent” countryside where the people are “honest”, value their daughters the same as their sons (even the child traffickers apparently charge the same discriminating only by age and blood type), and bury their bodies together. Chang-bok and Tae-in aren’t bad people, just members of a corrupt society who’ve internalised a sense of powerlessness that encourages them to be “humble” and complicit doing what they can to survive. Each marginalised by disability, Chang-bok walking with a pronounced limp and Tae-in rendered impotent by his inability to speak, they do not want to turn to “crime” but are trapped at the bottom of the social hierarchy and dependent on the illicit economy. Is Cho-hee any worse off with them than with the father who wouldn’t pay to get her back? The jury is most definitely out.

Voice of Silence streamed as part of the Glasgow Film Festival.

Original trailer (English subtitles)

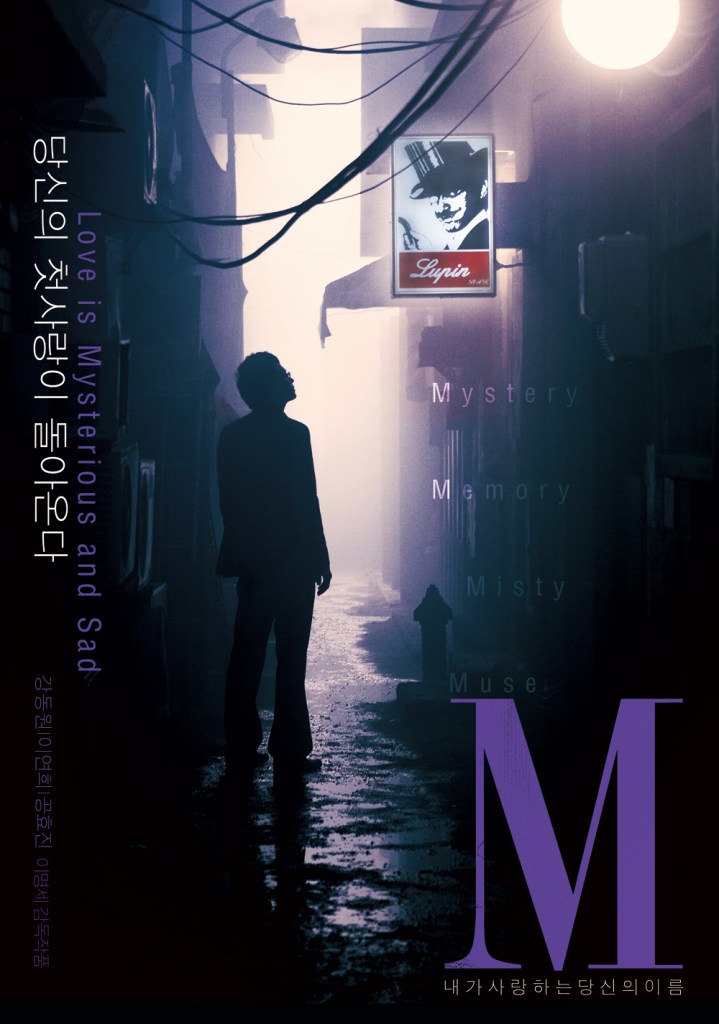

“More specific, less poetic” the distressed author hero of Lee Myung-se’s M (엠) repeatedly types after a difficult conversation with his editor. Almost a meta comment on Lee’s process, it’s just as well that it’s advice he didn’t take – M is a noir poem, a metaphor for an artist’s torture, and a living ghost story in which a man shifts between worlds of memory, haunted and hunted by unidentifiable pain. Reality, dream, and madness mingle and merge as a single kernel of confusion causes widespread panic in a desperate writer’s already strained mind.

“More specific, less poetic” the distressed author hero of Lee Myung-se’s M (엠) repeatedly types after a difficult conversation with his editor. Almost a meta comment on Lee’s process, it’s just as well that it’s advice he didn’t take – M is a noir poem, a metaphor for an artist’s torture, and a living ghost story in which a man shifts between worlds of memory, haunted and hunted by unidentifiable pain. Reality, dream, and madness mingle and merge as a single kernel of confusion causes widespread panic in a desperate writer’s already strained mind.