The Black Jack of Osamu Tezuka’s classic manga is a morally ambiguous figure who cultivates an image of callousness through asking for exorbitant sums to cure often desperate people, but in reality will usually treat seriously ill patients if touched by their plight or is content to collect the money from another source ensuring a kind of social justice is done. A spin-off manga written by Yoshiaki Tabata and illustrated by Yugo Okuma, Young Black Jack (ヤング ブラック・ジャック), was published from 2011 to 2019 and was set in the 1960s when Black Jack was gifted young medical student living through a politically turbulent era.

Broadcast in 2011, this television special meanwhile updates the action to the present day while acting as a kind of double origin story if one set in a more realistic world. As a nine-year-old boy, Black Jack asks his mother to meet him by the Christmas display in a local shopping mall. Not having had enough money to buy his mother a red rose, he patiently sits and draws one under the tree while otherwise oblivious to the news being broadcast on a large screen explaining that there has been a series of bombings in the city and the next target is this very mall. Black Jack’s mother has become mute after a traumatic incident but tries to call out to him only for the pair to be caught in the blast. Touched by their story, the genius doctor Honma (Masachika Ichimura) manages to save Black Jack by transplanting his organs and giving him a skin graft while his mother remains in a coma.

The story then jumps to the present day with Black Jack (Masaki Okada) a medical student with an underground lair where he keeps his comatose mother (who hasn’t aged at all in 15 years) and operates as a backstreet doctor treating undocumented migrants and yakuza. Aside from emphasising his contradictory nature as someone who both treats anyone who requires treatment no matter of their social status yet simultaneously demands incredible sums of money for doing so, associating with these kinds of people also places Black Jack among the lower ranks of society which is something that niggles at snooty doctor Naoki (Yukiyoshi Ozawa). Naoki is sort of betrothed to Yuna (Riisa Naka), the daughter of the chief doctor at a prestigious university hospital who is herself in the middle of taking her final exams to become a doctor.

Familiar to fans of the manga, Naoki is Black Jack’s opposite number. As he tells Yuna, there are two kinds of doctors. Those who save lives and those who kill. In the manga, Naoki was a doctor traumatised by his wartime experiences who often wants to euthanise the patients that Black Jack is trying to save believing that there is no way to save them. Having encountered Black Jack cooly saving a patient who collapsed in the street, Yuna asks Naoki what he thinks makes a good doctor and he tells her it’s the belief that medical science has no limits and the doctor is omnipotent. Yet he later says just the opposite, telling Yuna that she is being childish and of course there are limits to what medical science can achieve so in effect he’s giving up. Black Jack meanwhile does believe in his own omnipotence, even if that’s not always such a good thing, and is confident he can save any patient even if in the end he cannot save the one most close to him (perhaps because she wanted him to stop trying).

The film does not however go into very much detail and only gives brief snippets of backstory such as Black Jack’s mother going mute after a shadowy man enters and leaves their home while hinting at potential future stories in his opposition to Naoki who objects to him partly out of snobbishness, and a potential romance with Yuna who has now shifted away from the elitism that coloured her family towards a more altruistic kind of medicine represented by Black Jack even in his aloofness. Nevertheless, the film makes no real attempt to transcend its origins as a television movie, not that it has to, and is hampered by an uninspired script and low production values which contribute to its relatively more naturalistic setting yet sit awkwardly with the more outlandish parts of the narrative such as Black Jack’s keeping his mother in cryogenic status for 15 years or being able to transplant all of someone’s organs at once and in under 10 minutes. Still, as a minor outing for the iconic character it’s entertaining enough for fans of the franchise.

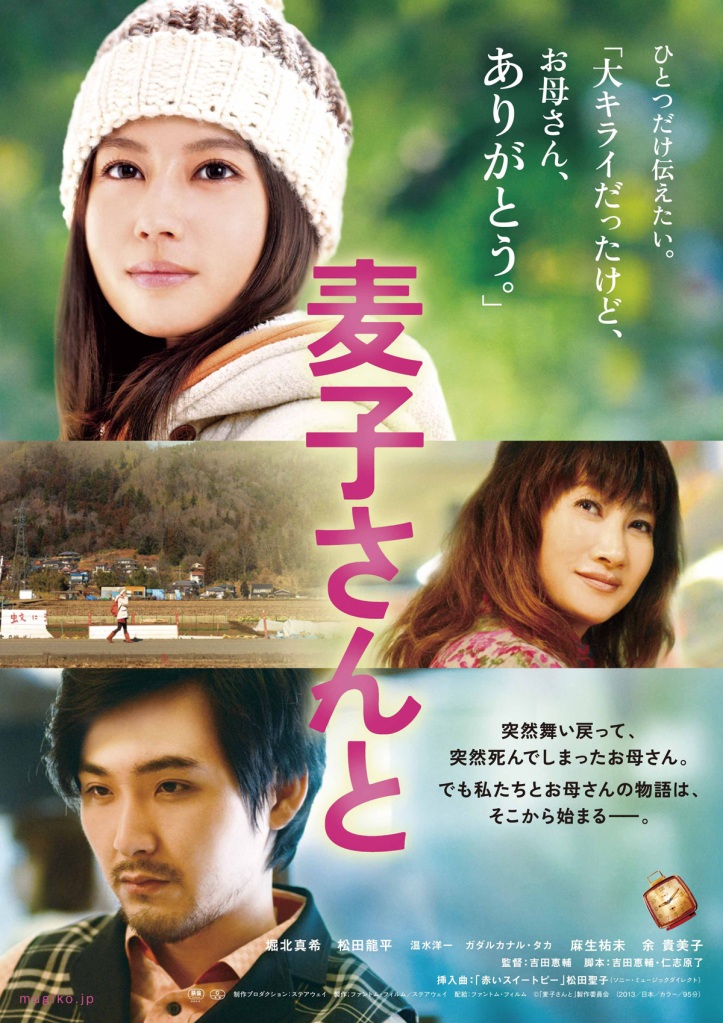

How many times were you told as a child, someday you will understand this? There are so many things you don’t see until it’s too late, and children being as they are, are almost programmed to see things from a self directed tunnel vision. Such is the case for Mugiko – a young woman with dreams of becoming an anime voice actress who is suddenly reunited with her estranged mother of whom she has almost no memory.

How many times were you told as a child, someday you will understand this? There are so many things you don’t see until it’s too late, and children being as they are, are almost programmed to see things from a self directed tunnel vision. Such is the case for Mugiko – a young woman with dreams of becoming an anime voice actress who is suddenly reunited with her estranged mother of whom she has almost no memory.