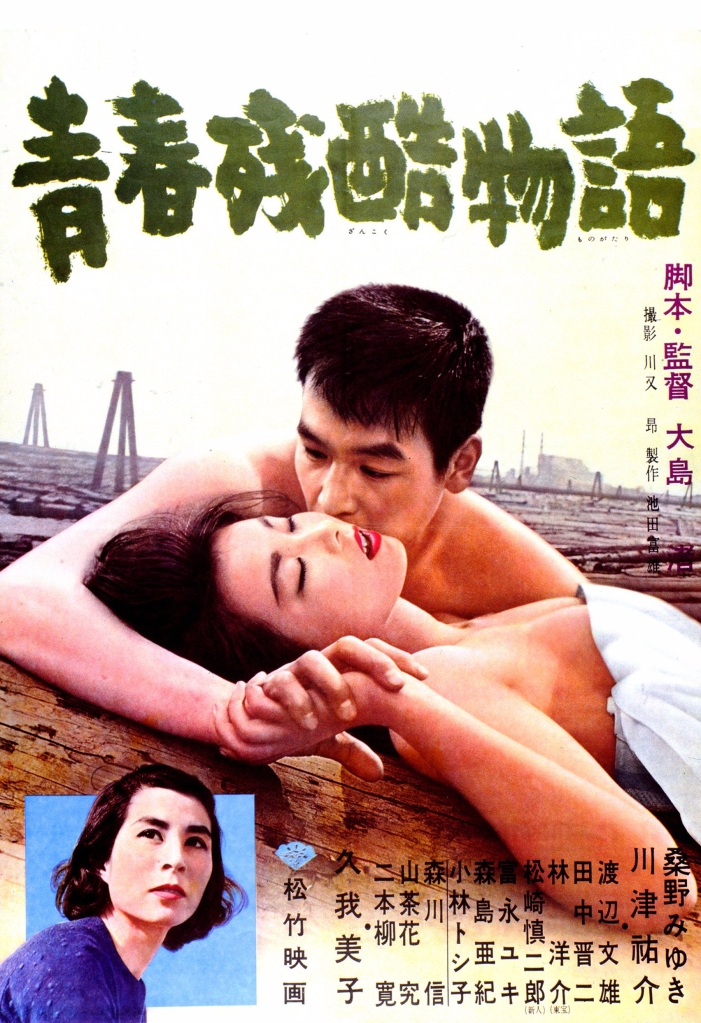

More interested in politics than cinema and never quite at home in the studio system, Nagisa Oshima began his career at Shochiku as one of a small group of directors promoted as part of the studio’s effort to reach a youth audience they feared their particular brand of inoffensive melodrama was failing to capture. Like The Sun’s Burial, Cruel Story of Youth (青春残酷物語, Seishun Zankoku Monogatari) is a nihilistic tale of a fracturing society, but it also looks forward to Night and Fog in Japan in its insistence that youth itself is a failed revolution and this generation is no more likely to escape existential disappointment than the last.

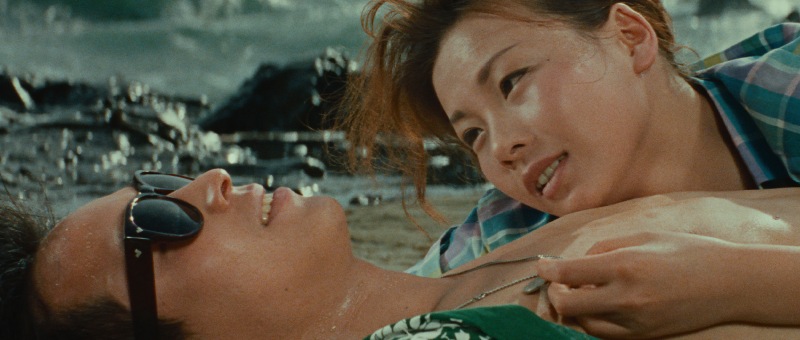

The film opens with teenager Makoto (Miyuki Kuwano) and her friend Yoko (Aki Morishima) trying to get free rides from skeevy middle-aged men rather than having to pay for a cab. As you might expect, that’s a fairly dangerous game and while it might be alright while there’s two of you, as soon as Yoko has been dropped off, the driver changes course and suggests going for dinner only to park in front of a love hotel and try to drag Makoto inside. Luckily, or perhaps not as we will see, she is “rescued” by young tough Kiyoshi (Yusuke Kawazu), a student and angry if politically apathetic young man. Struck by his manly white knight act, Makoto takes a liking to Kiyoshi but he too later rapes her under the guise of satisfying her curiosity about sex to which he attributes her ride hailing activities. After this violent genesis, they fall in “love” but continue to struggle against an oppressive society.

We assume that the “cruel story of youth”, and it is indeed cruel, that we are witnessing is that of Makoto and Kiyoshi, but it’s also that of her slightly older sister Yuki (Yoshiko Kuga) and her former lover Akimoto (Fumio Watanabe) who has become a conflicted doctor to the poor betraying himself by financing the clinic through charging for backstreet abortions. Yuki complains to her apathetic father that they were strict with her in her youth, that she’d get a hiding just for coming home after dark, whereas Makoto can stay out all night and not get much more than a stern look. Her father explains that times were different then, “We thought we had new horizons. We started again as a democratic nation, and it was a responsibility that went hand in hand with freedom. What can I say to this girl today?” admitting both the failures of the past and the mistaken future of a society that actively resists change.

Yuki and Akimoto were part of the post-war resistance, left-wing students like the older generation of Night and Fog in Japan, who’d actively fought for real social change but had seen that change elude them. Yuki, we hear, left Akimoto for an older man but perhaps now regrets it along with her half-finished revolution. She may not approve of her sister’s choices, but she also on some level admires her for them or at least for the strength of her rebellion even if it will ultimately be as fruitless as her own. “This is a cruel world and it destroyed our love” Akimoto laments, mildly censuring the youngsters in suggesting that his love was pure and chaste because they vented their youthful frustrations through political action whereas this generation is already lost to the mindless hedonism of unbridled sexuality.

He forgives them, because he feels that their plight is a direct result of his failure to bring about the better world, but there is also a suggestion that it is a lack of political awareness which is somehow trapping the young. Oshima cuts from footage of the April Revolution in Korea which is described as a “student riot” in the news to a protest against the Anpo treaty at which Kiyoshi and Makoto look on passively from the sidelines. “I think taking part in the demonstrations is stupid”, Makoto’s friend Yoko tells a prospective boyfriend, “why don’t we think about getting married instead?”, drawing a direct line between social conservatism and political inaction.

Makoto and Kiyoshi rebel by using, or to a point not using, their bodies as a direct attack on the society. Following their rather odd and troubling meeting, the pair earn their keep through repeating the experience. Makoto picks up men who will inevitably have an ulterior motive, and Kiyoshi rescues her, extorting money from their targets. Yet it is Kiyoshi who is forced to prostitute himself, gaining financial support as a gigalo kept by a wealthy middle-aged housewife who is just as sad and defeated as Yuki and Akimoto, dissatisfied with the path her life has taken and in her case attempting to escape it through passion and control exerted over the body of a young man. Though the consequences of a becoming a kept man may be different than those Makoto would face should the less “nice” delinquents get their hands on her, they do perhaps fuel his sense of violent emasculation which he channels into a pointless act of revenge against the society in the form of its most powerful, wealthy middle-aged men whose misogyny he claims to abhor while simultaneously mirroring and directly exploiting.

“Someone needs to be responsible” a strangely sympathetic policeman insists, chiding Kiyoshi that at heart he’s just a petty criminal who liked having money no matter how he might have tried to dress it up. “You’re just like them, you’re a victim of money too”, he adds correctly diagnosing the flaws of an increasingly consumerist society. Only, no one takes responsibility. Kiyoshi’s lady friend pulls stings. It turns out her husband does business with Horio, one of Makoto’s pick ups who despite being nice and kind still had his way with her and then reported Kiyoshi for extortion. Akimoto explained that their failures would drive them apart, but Kiyoshi swore they’d always be together only to wonder if in his love for her the only thing to do is save Makoto from his corrupting influence though she does not want to leave him. We won’t be like you, Kiyoshi countered, because we have no dreams with which to become disillusioned. But youth itself is a failed revolution, and the force which destroys them is perhaps love as they meet their shared destinies at the hands of an increasingly cruel society.

Cruel Story of Youth is currently streaming on BFI Player as part of the BFI’s Japan season.

Original trailer (no subtitles)