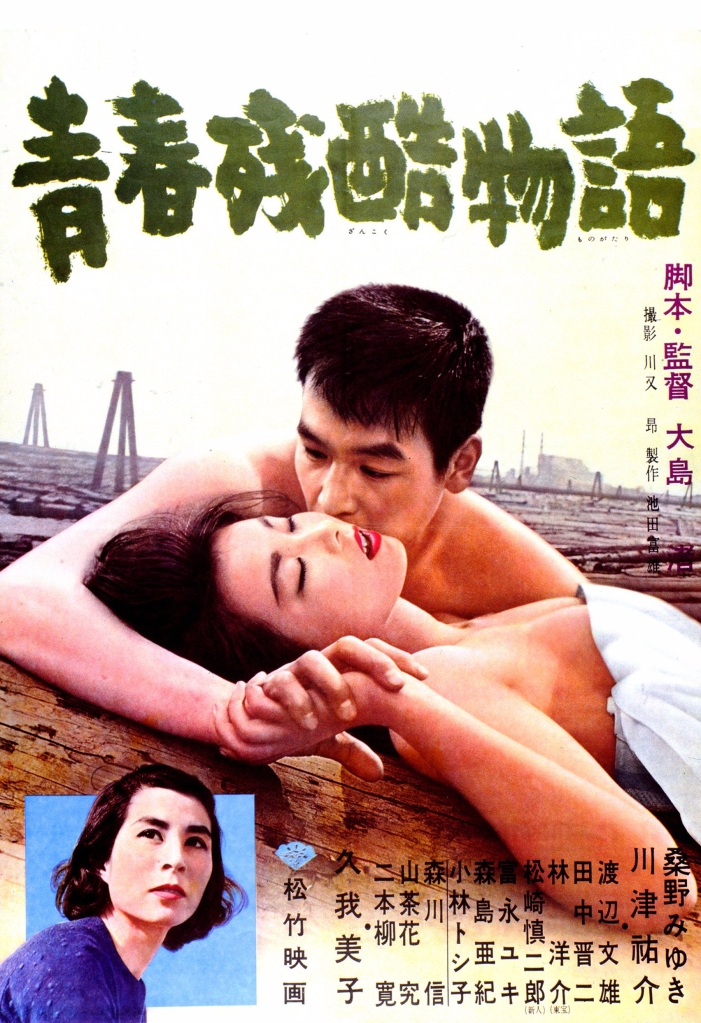

Tamotsu Tamura is best known as a screenwriter who worked closely with Nagisa Oshima, though he did actually direct a film himself at the beginning of his career. Having originally planned to become a reporter, Tamura was offered a job at Sankei Shimbun but his employment was postponed for medical reasons and he decided to retake the entrance exam for Shochiku joining the studio in 1955. Unfortunately Volunteering for Villainy (悪人志願, Akunin Shigan, AKA The Samurai Vagabonds) was not successful at the box office and Tamura soon left Shochiku along with Oshima and became a screenwriter at his independent production company.

In any case, the film is very reminiscent of New Wave filmmaking both in terms of theme and aesthetic. It repurposes a moribund quarry town as an almost literal purgatorial space casting the protagonists into a deep hole from which they are eternally unable to escape. As the film opens, a collection of children are taunting a young woman, Hide (Kayoko Hono), calling her a murderer and castigating her for failing to die, though it later transpires that they’ve been hired by a henchmen of Tatsuo (Masahiko Tsugawa), the brother of the man she was involved in double suicide with who is determined to become some kind of local dictator.

But even he is in some ways rebelling against his powerlessness as the son of a local politician he brands as phoney and corrupt. Tatsuo claims he hates people who claim to be good but aren’t, in much the same way as Hide claims she can no longer trust anyone. Tatsuo seems to want revenge for the death of his brother for which he holds Hide responsible but insists he doesn’t want to settle it with money nor is he in favour when a shady local man makes vague allusions to having her bumped off.

When a new recruit, Yasuo (Fumio Watanabe), joins the quarry he becomes its latest kicking bag not least because it was Hide who escorted him into town. Yasuo has a stammer and incredibly meek manner that leans towards obsequiousness. “You’re as obedient as a dog,” people often remark with Tatsuo later astutely observing that he’s the sort of person who can’t do anything without someone telling him to do it. Yet it later seems as if his desire to obey, to be liked and accepted by those around him, has led him to commit a terrible crime claiming that he only did what everybody wanted done even if they were too afraid to say so.

Ashamed of himself and his corrupted masculinity Yasuo alternately rebels and overcompensates. He refuses to hit Hide when ordered to by Tatsuo, and to sleep with her when forced by the other men, but later hits and sleeps with her possibly not quite consensually when his masculinity is challenged. The irony is that Tatsuo who claimed he wouldn’t tolerate anyone defying him cannot control Hide’s free spirit and is therefore unable to overcome his powerlessness. He bullies and harasses her insisting that she leave town, but Hide refuses to go and is continually unbothered by the way she’s treated. Hide also eventually rejects Yasuo for his cowardice, severing her ties to him on realising that he informed on one of the other men who was fugitive from justice to curry favour with Tatsuo and take the heat off himself. She tells Tatsuo that though he’s always wanted things his own way, she’s always decided for herself, infuriating him with her free decision to leave having realised how petty and meaningless it was to stay in this petty and meaningless purgatory of broken and hopeless men.

Tamura shoots with a roving and curious camera that takes on a life of its own swooping through the dorms but lends a degree of mythic eeriness to the final confrontation in the quarry as the workers begin to dot the skyline looking down at Hide below in a scene somehow reminiscent of L’Avventura. The town’s only bright spot is presented by Tatsuo’s younger sister Kiyoko (Chiaki Tsukioka) as the voice of reason even as she brands everything boring and meaningless but thereby suggesting that it might not have to be this way. Her words, however, fall on largely deaf ears save those of Hide perhaps finally awake to her own agency only to have it immediately crushed by fragile masculinity.