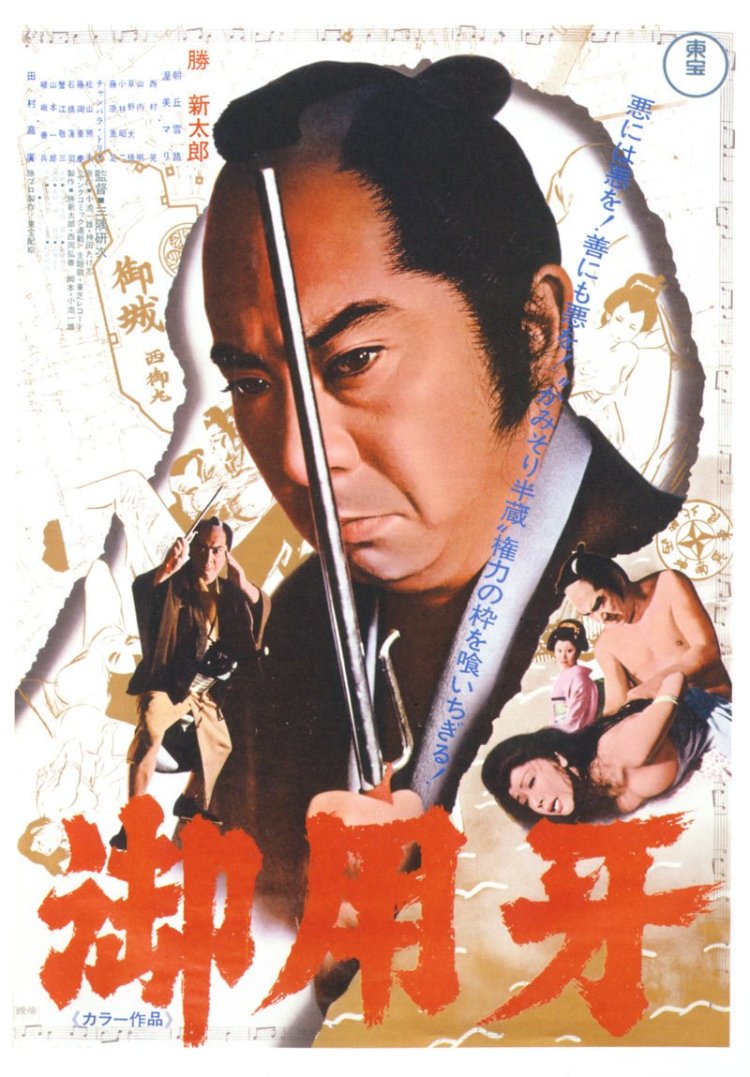

Japanese cinema was in a state of flux in the early ‘70s. Audiences were dwindling. Daiei, a once popular studio known for polished, lavish productions folded while Nikkatsu took the proactive measure to rebrand itself as a purveyor of soft core pornography. Toho did not go so far, but in its first foray into a new kind of jidaigeki, exploitation was the name of the game. Hanzo the Razor: Sword of Justice (御用牙, Goyokiba) was released in 1972 – the same year as the beginning of another seminal series, Lone Wolf and Cub, which was produced by Hanzo’s star, former Zatoichi actor Shintaro Katsu, who also happens to the be brother of the franchise’s lead Tomisaburo Wakayama. Like Lone Wolf and Cub, Hanzo the Razor is based on a manga by Kazuo Koike whose work later provided inspiration for the Lady Snowblood films, and is directed by Lone Wolf and Cub’s Kenji Misumi. It is then of a certain pedigree but its intentions are different. More obviously comedic in its exaggerated, unpleasant sexualised “humour”, Hanzo the Razor is also a tale of the systemic corruption of the feudal order but one which casts its “hero” as a noble rapist.

Japanese cinema was in a state of flux in the early ‘70s. Audiences were dwindling. Daiei, a once popular studio known for polished, lavish productions folded while Nikkatsu took the proactive measure to rebrand itself as a purveyor of soft core pornography. Toho did not go so far, but in its first foray into a new kind of jidaigeki, exploitation was the name of the game. Hanzo the Razor: Sword of Justice (御用牙, Goyokiba) was released in 1972 – the same year as the beginning of another seminal series, Lone Wolf and Cub, which was produced by Hanzo’s star, former Zatoichi actor Shintaro Katsu, who also happens to the be brother of the franchise’s lead Tomisaburo Wakayama. Like Lone Wolf and Cub, Hanzo the Razor is based on a manga by Kazuo Koike whose work later provided inspiration for the Lady Snowblood films, and is directed by Lone Wolf and Cub’s Kenji Misumi. It is then of a certain pedigree but its intentions are different. More obviously comedic in its exaggerated, unpleasant sexualised “humour”, Hanzo the Razor is also a tale of the systemic corruption of the feudal order but one which casts its “hero” as a noble rapist.

Honest and steadfast police officer Hanzo (Shintaro Katsu) usually skips the annual swearing in ceremony but this year he’s decided to make an appearance. He appears to have done so to make a personal stand by refusing to sign the policeman’s oath because he knows everyone else is breaking it. Officers may not be doing something so obvious as accepting cash for preferential treatment, but they gladly accept free drinks, gifts from lords, and entertainment in the local geisha houses. Hanzo’s actions, honest as they are, do not go down well with his fellow officers and if he can’t figure something out on time, Hanzo faces the possibility that his career in law enforcement may come to an abrupt end when contracts are up for renewal at the end of the year.

Whatever else Hanzo is, he doesn’t like bullies or those who abuse their authority and the trust placed in them by those they are supposed to be protecting. More than just saving his own skin, Hanzo is determined to unmask the hypocrisy and corruption of his boss, Onishi (Ko Nishimura), who he discovers shares a mistress with a notorious killer still on the run. Chasing this early thread, Hanzo walks straight into a chain of corruption which leads all the way to the top.

At his best, Hanzo is a steadfast champion of the people who remain oppressed by the corrupt and venal samurai order. Far from the a by the books operative, Hanzo is prepared to do what’s best over what’s right as in his decision to help a pair of siblings who are faced with a terrible dilemma trying to care for a terminally ill father. He’s also extremely well prepared, having installed a host of booby traps and hidden weapons caches throughout his home to deal with any conceivable threat. Dedicated in the extreme, Hanzo has also spent long hours testing his torture techniques on himself to find out the exact point of maximum efficiency for each of them.

Here’s where things get a little more unusual. As Hanzo climbs down from a bout of torture, a huge erection is visible inside his loincloth, prompting him to reveal that it’s pain which really turns him on. Later we see Hanzo doing some maintenance on his “tool” which involves placing it on a wooden board bearing a huge penis shaped indent, and hitting it repeatedly with a hammer before ramming it back and forth into a bag of uncooked rice. Each to their own, but Hanzo derives no pleasure from these acts – they are simply to make sure his “special interrogation method” runs at maximum efficiency. Which is to say, Hanzo’s preferred technique for getting women to talk amounts to rape but as each of them fall victim to his oversize member they cry out in pleasure, willing to spill the beans just to get Hanzo to finish what he started. Playing into the fallacy that all women long to be raped, Hanzo’s inappropriate misuse of his own authority is played for laughs – after all, the women eventually enjoy themselves so it’s no harm done, right? Troubling, but par for the course in the world of Hanzo.

This essential contradiction in Hanzo’s character – the last honourable man who nevertheless abuses his authority in the course his duty (though he apparently takes no personal pleasure in the act), is reduced to a roguish foible as he goes about the otherwise serious business of taking down corrupt authority and ensuring the law protects the people it’s supposed to protect. Odd as it is, Hanzo’s world is an strangely sexualised one in which sexually liberated women wield surprising amounts of power. Hanzo is assured one of his targets has “no lesbian tendencies” as other older court ladies are said to, while a gaggle of camp young men gossip about the size of Hanzo’s world beating penis. In an odd move, Misumi even includes a penis eye view of Hanzo’s techniques, superimposed over the face of a woman writhing in pleasure. Surreal and broadly humorous if offensive, Hanzo the Razor: Sword of Justice is very much of its time though strangely lighthearted in its obviously bizarre worldview.

Original trailer (English subtitles)

“Sometimes it feels good to risk your life for something other people think is stupid”, says one of the leading players of Masaki Kobayashi’s strangely retitled Inn of Evil (いのちぼうにふろう, Inochi Bonifuro), neatly summing up the director’s key philosophy in a few simple words. The original Japanese title “Inochi Bonifuro” means something more like “To Throw One’s Life Away”, which more directly signals the tragic character drama that’s about to unfold. Though it most obviously relates to the decision that this gang of hardened criminals is about to make, the criticism is a wider one as the film stops to ask why it is this group of unusual characters have found themselves living under the roof of the Easy Tavern engaged in benign acts of smuggling during Japan’s isolationist period.

“Sometimes it feels good to risk your life for something other people think is stupid”, says one of the leading players of Masaki Kobayashi’s strangely retitled Inn of Evil (いのちぼうにふろう, Inochi Bonifuro), neatly summing up the director’s key philosophy in a few simple words. The original Japanese title “Inochi Bonifuro” means something more like “To Throw One’s Life Away”, which more directly signals the tragic character drama that’s about to unfold. Though it most obviously relates to the decision that this gang of hardened criminals is about to make, the criticism is a wider one as the film stops to ask why it is this group of unusual characters have found themselves living under the roof of the Easy Tavern engaged in benign acts of smuggling during Japan’s isolationist period.