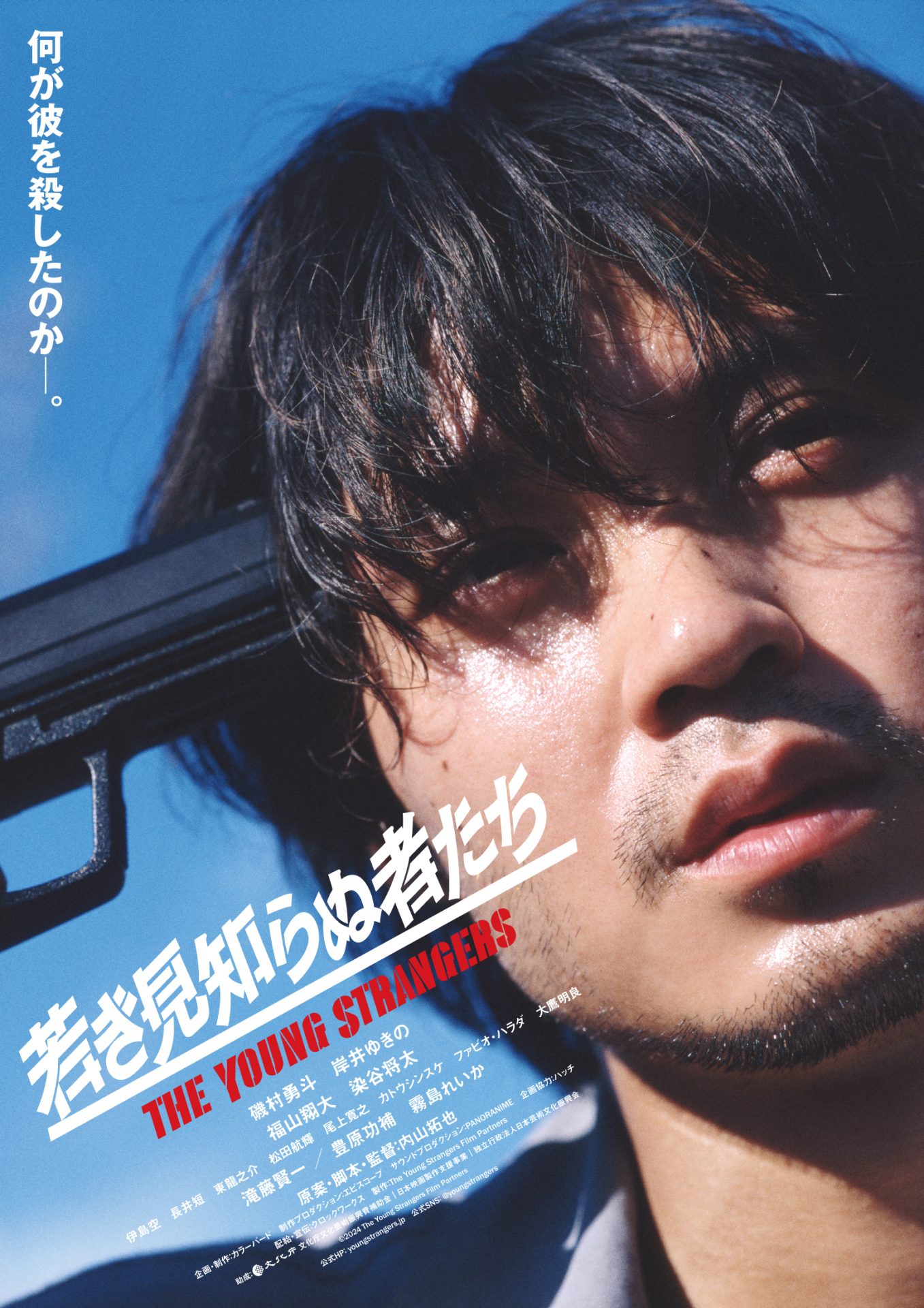

You have to protect your space from the violence of this world, a compromised father advises his sons, yet it’s something that neither he nor they are fully capable of doing. Billed as the “commercial debut” from the director of the equally emotionally devastating Sasaki in my Mind, Takuya Uchiyama, The Young Strangers (若き見知らぬ者たち, Wakaki Mishiranu Monotachi) paints a somewhat bleak portrait of contemporary Japan as place of desolation and abandonment, but at the same time is melancholy more than miserable in the earnestness with which they all dream of a better life somewhere beyond all of unfairness and injustice.

But Ayato (Hayato Isomura) seems to know that he’s burdened with some kind of karmic fate. His life oddly echoes that of his former policeman father and takes on an ironic symmetry even as he was unfairly left to pick up the pieces as a teenager adrift in the wake of parental betrayal. Now his late 20s, Ayato is a worn out and dejected figure who barely speaks after years of doing multiple jobs, in addition to running the snack bar his parents opened as a new start, to pay off the debts his father left behind. Now his mother has early onset dementia and her care is also something else he must manage as best he can with support from his girlfriend Hinata (Yukino Kishii), a nurse, and less so from his conflicted brother, Sohei (Shodai Fukuyama), who has a path out of here as an MMA champion if only he can stick to the plan and keep up with his training.

As his best friend Yamato (Shota Sometani) points out, he’s hung onto everything his father left him but is equally in danger of losing his future. He seems wary of his relationship with Hinata, afraid to drag her into his life of poverty and hardship, while he watches friends get married and start families. He once had a promising future too, as the star of the school football team, but like everything else that came to an abrupt end in the wake of family tragedy. There are hints of trouble with law in his younger years that may have made it even more difficult for him to earn a living wage, along with giving him an unfavourable view of authority figures. Seeing another young man hassled by the police, he steps in to inverse but ends up in trouble himself. The policemen, take against him and when he’s beaten up by thugs who drag him out of the bar, they arrest him instead and let the others go. Time and again, bad actors seem to prosper and get away with their crimes, while good people like Ayato continue to suffer. When Yamato tries to come to his defence and questions the police, they lie and tell him Ayato’s just a waster as if the world were better off without him.

The boys have this game they play where put two fingers up against the back of a friend’s head and shout “bang”. It’s like there’s a bullet that always coming for them, and Ayato too fantasises about shooting himself in the head to escape this misery. Sohei, meanwhile, makes violence his weapon in taking the martial arts his father left him to forge a new path for himself while vowing not to be intimidated by violence. But violence is all around them from the literal kinds to that of an uncaring and oppressive society, and as much as Ayato fights in his own way to protect his family he can’t keep them all together nor the darkness at bay. He badly needs Sohei’s help, but also knows he can’t ask him to give up his way out or take away his future while Sohei is already pulling away. He thinks it’s time to look into a more permanent solution for their mother, and that they should let the past go, but Ayato wants to hold on to all of it as a means of giving his life meaning. “It’s not your fault, but it will be if it carries on,” a sympathetic neighbour tells Ayato after finding his mother in his cabbage patch again and leaving him to one again clear up the mess. Haunted by images of the past that in Uchiyama’s masterful staging segue into and out of the present, Ayato desperately searches for a way out of his suffocating existence, but encounters only betrayal and injustice amid the constant violence of an indifferent society.

The Young Strangers screened as part of this year’s Camera Japan.

Trailer (no subtitles)