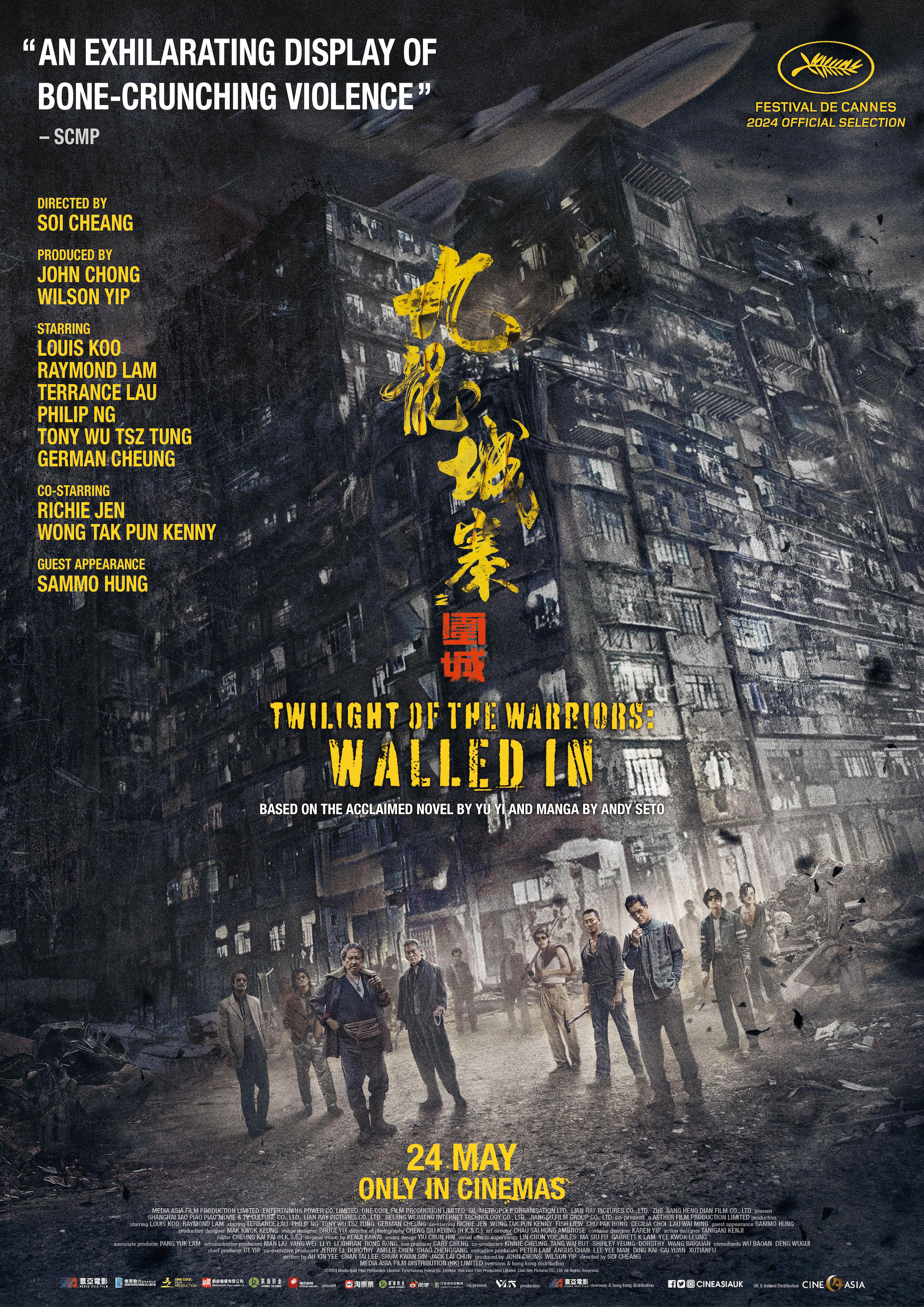

In Kowloon Walled City, you give help, you get help. Sometimes described as a colony within a colony, by the late 1980s the settlement was largely ungovernable and literal law unto itself save for the triads who maintained what little order there was. Yet in Soi Cheang’s Twilight of the Warriors: Walled In (九龍城寨.圍城) it’s a place of comfort and security, a well functioning community that as its leader Cyclone (Louis Koo Tin-lok) points out may be unpalatable for “normal” people but provides a point of refuge for the exiled and hopeless.

It’s difficult not to read it and Cyclone himself as embodiments of Hong Kong that is slowly disappearing. Dying of lung cancer, Cyclone is aligned with the fate of the walled city as someone whose time is running out, tired and world weary but still hanging on. In the opening sequence set 20 or so years before, we see Cyclone stand up to an apparent dictatorship and institute what seems to be a more egalitarian form of government though one obviously defined by violence. Nevertheless, when refugee Lok (Raymond Lam Wui Man) lands up there originally suspicious of Cyclone having been duped by local gangster Mr Big (Sammo Hung Kam-bo), he discovers him to be a stand up guy looking after those in his community and generally keeping the peace. Nevertheless, Lok’s arrival is the fatalistic catalyst for the opening of old wounds amid the free for all of the mid-80s society in which the Walled City, sure to be bulldozed, has just become a lucrative property investment.

Mr Big and his crazed henchman King represent this new order, amoral capitalistic consumerists who care little for the conventional rules of gangsterdom. Their bid to seize the Walled City has its obvious overtones as they seek to replace the (generally) peaceful egalitarian rule of Cyclone with something that appears much more authoritarian and ruthless. Believing himself to be a stateless orphan, Lok tries to keep his head down saving everything he can to buy a fake Hong Kong ID card which is also in its way a quest for identity not to mention a homeland and a sense of belonging. He finds all of these things, along with a surrogate father figure, in the Walled City only to have the new home he’s discovered for himself ripped out from under him because of a twist of fate. When he teams up with a trio of other young men who all owe their lives to Cyclone and the Walled City to attempt to take it back, it’s also an attempt to reclaim an older, more autonomous Hong Kong that exists outside of any kind of colonial control as evidenced by his final statement that no matter what happens some things don’t change.

This sensibility extends to the casting of the film which includes a series of Hong Kong legends including a notable appearance from the legendary Sammo Hung not to mention Louis Koo alongside a generation of younger stars such as Tony Wu and Terrance Lau Chun-him. Adapted from the manhua City of Darkness by Andy Seto, the film opens with a flashback to the original war for control of the Walled City that hints at deeper, extended backstories otherwise unexplored though equally mythologised by those who impart them to them Lok, a prodigal son and eventual inheritor of the City’s legacy. Even so, the comic book elements sometime distract from Soi Cheang’s otherwise evocative if hyperreal recreation of the Walled City slum or the political subtext that can be inferred in the presence of supernatural abilities such as those which seem to grant King near invincibility.

In any case, Soi Cheang looks back equally towards the history of heroic bloodshed in particular in his tale of brotherhood and loyalty in which the secondary antagonist is literally imprisoned by his own futile desire for a pointless vengeance on the descendent of a man who had wronged him but was already long dead himself. As he’d said, the future of the Walled City is in the hands of the younger generation who choose to end the cycle by setting him free rather than imprison themselves along with him while defending their home as well as they can. With some incredibly well designed action sequences including one that make its way onto a double-decker bus, Soi Cheang’s beautifully staged action thriller as its name suggests has a rather elegiac quality but also the spirit of resistance in its gentle advocation for the importance of supportive communities.

Twilight of the Warriors: Walled In is in UK cinemas from 24th May courtesy of CineAsia.

UK trailer (Traditional Chinese & English subtitles)