There isn’t any denying that the last two years have been extremely difficult for everyone all around the world. Multi-strand “main melody” drama in praise of frontline workers Ode to the Spring (没有一个春天不会来临, méiyǒu yī gè chūntiān bùhuì láilín) may in itself be slightly optimistic in that its perspective is clearly one assuming that the worst is over and the pandemic is largely a thing of the past. Ironically the film’s release, previously scheduled for April, had to be delayed until the early summer because of rising cases in Mainland China. Nevertheless, its messages of hope and the importance of community have lost none of their power while the film’s willingness to admit that some things could have been handled better, even without expressly stating by who, is surprisingly subversive.

Structured as a multi-strand drama rather than a traditional omnibus movie, the film follows five groups of people mainly in Wuhan at the beginning the outbreak. The first story revolves around a young man, Nanfeng (Yin Fang), whose relationship with local florist Xiaoyu (Zhou Dongyu) had become strained by his decision to move to Shanghai to earn more money for their future. As the New Year Spring Festival approaches, he returns to Wuhan in an attempt to patch things up oblivious of the new disease engulfing the city. Xiaoyu and her mother, who had not approved of him, have each been hospitalised but were separated in the chaos and are now in different hospitals with no way to stay in touch. In a mild rebuke to modern day consumerism, the message that Nanfeng is forced to learn is that he should have been thinking how best to support his community rather than leaving to make more money in Shanghai. Running all around town looking for Xiaoyu’s mother, he eventually wins her approval but is simultaneously warned that he is too impulsive and should think more about what it is others actually want rather than giving them what he thinks they should have.

Meanwhile a pair of migrant workers struggle to make a living but are given a load of face masks and told to sell them in Wuhan. They too are little aware of how bad things have already become. The older of the drivers is rebuked by his wife because he hasn’t come home in several months and his daughter is beginning to forget him. Though they become increasingly afraid of infection, the truckers maintain their compassion helping an elderly lady and her granddaughter, whose parents are already in a quarantine centre, get to a hospital and then deciding that perhaps they shouldn’t be trying to profit from the pandemic no matter their own desperate circumstances.

Then again, the film is surprisingly frank about the supply problems in the hospitals which have already run out of high grade medical masks while medics are close to burn out. A doctor is forced to sleep in his car because he’s technically on call. His wife, a nurse, chooses to join him rather than stay in the hotel room they’ve been provided while their son is cared for by his grandparents. He calls a man to tell him his father has passed away and ask for additional documentation to release the body, but the grieving son is himself in a quarantine centre as are all the other family members who have so far survived. The inability to save a fellow doctor who was shortly to become a father almost breaks him, while his wife wonders what’s to become of their son if they should both fall ill. Despite having scolded the boy on the phone about not doing his homework, the doctor has recorded a poignant voice message for his son just in case letting him know that he bought him the toy he wanted for his birthday and has been paying attention even if it didn’t seem like it at the time.

The themes of parental separation echo through each of the stories, Xiaoyu is separated from her mother, the trucker cannot return to his family because of the lockdowns and his precarious financial position, and the doctor is staying away from his son to treat the sick. In the final strand, a naughty little boy obsessed with legendary child warrior Nezha is separated from his doctor mother (Song Jia) who is despatched to Wuhan to help with the relief effort while his father (Huang Xiaoming), unused to taking care of him, is preoccupied because he unwisely invested in buying a bus he cannot now use because no one is allowed to go anywhere. The boy dreams of visiting a local Buddha statue and getting him to “awaken” from his “quarantine” to show the virus who’s boss only for the Buddha to let him take on Nezha’s form to stamp on those nasty viruses so his mum can come home.

Similarly, the head of a local neighbourhood committee struggles to deal with complaints about a young woman playing piano at all hours while left home alone because her mother is a doctor staying at the hospital. Mr. Wang (Wang Jingchun) becomes something of a local hero, selflessly caring for the residents of a series of apartment blocks ensuring they get food deliveries and dealing with disputes. When he comes down with a fever and has to isolate, the whole block turns out their lights in support waving the torchlight on their phones like tiny stars shining in the distance. It’s here that the film’s real message lies in praising the value of community, not just the doctors and frontline health workers but the civil servants who kept everything running and the ordinary people who did their best to follow the rules and stay at home, while also hinting at some of the failures in the response from the random veg that keeps turning up at the depo to lack of PPE and the total disregard for the migrants stuck far from home in the midst of an economic collapse. Shot by five directors, the strands each have idiosyncratic flare from the chaotic handheld of the hospital scenes to the gentle romance of Nanfeng’s quest and the cheerful adventures of the would-be-Nezha but are otherwise of one voice in the film’s consistent messaging of mutual solidarity and praise for frontline workers.

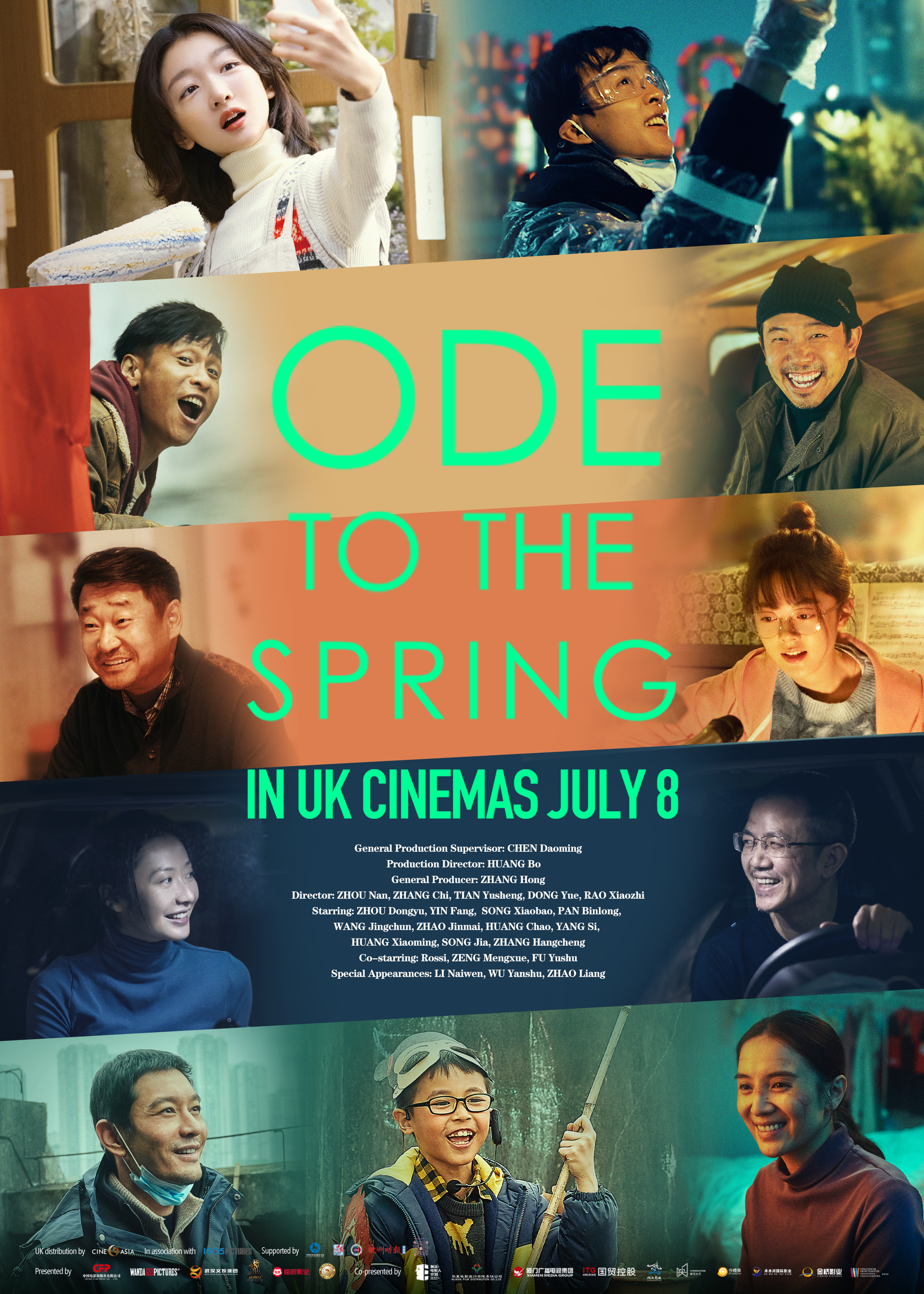

Ode to the Spring opens in UK cinemas on 8th July courtesy of CineAsia.

International trailer (English subtitles)