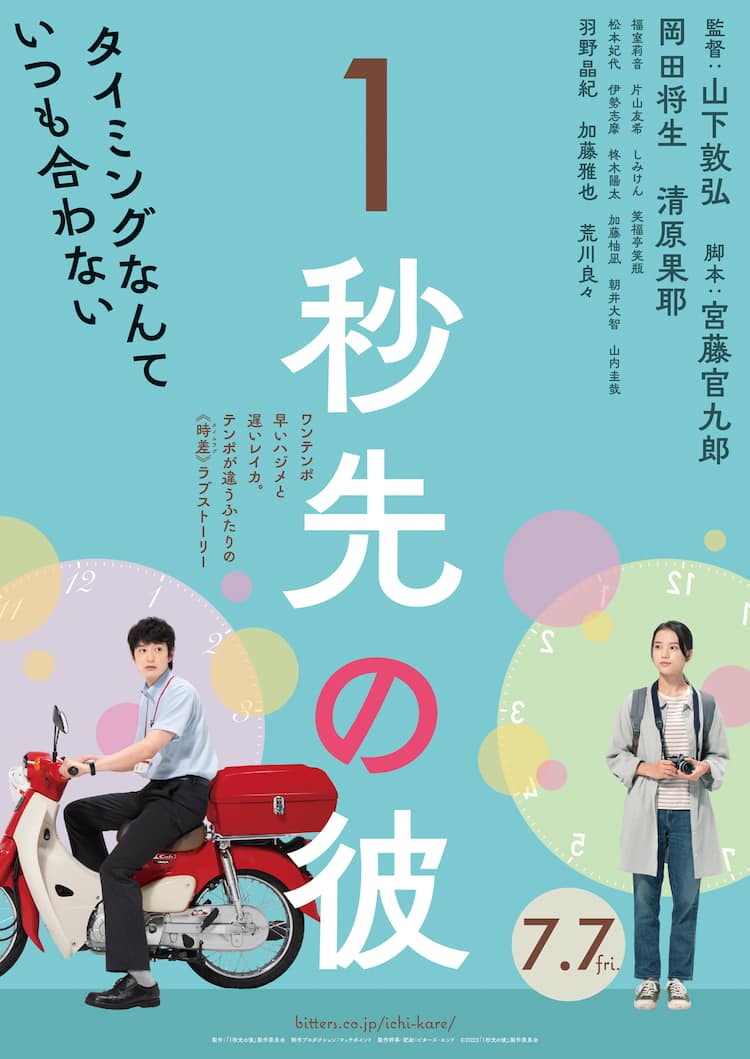

If you’re a step ahead and someone else is a step behind, then the gap between you ought to be twice as big but in an odd kind of way it can bring you closer. At least, that’s how it is for the protagonists of Nobuhiro Yamashita’s One Second Behind, One Second Ahead (1秒先の彼, Ichibyo Saki no Kare), a remake of the Taiwanese rom-com My Missing Valentine scripted by Kankuro Kudo.

Kudo wisely avoids some of the awkwardness of the original by reversing the genders of the misaligned romantics so that it’s now male post office worker Hajime (Masaki Okada) who wakes up to realise that he’s lost an entire day while having no recollection of how he got sunburnt or why there’s sand in his trousers. The host of a radio show he’s fond of listening to asks him about something he’s lost, causing him to remember his father who went out one evening for ginger and then never came back. Hajime’s problem is that he’s always a little ahead of himself, in too much of a hurry to fully grasp the situation around him. That might be one reason that he falls so hard for singer-songwriter Sakura (Rion Fukumuro) and becomes far more invested in the relationship than might be wise for someone you’ve only just met.

Reika (Kaya Kiyohara), meanwhile, is always a little bit behind. Shy and somewhat reserved she struggles to get her words out and while Hajime has often left before the end of a conversation she is usually left hanging by an inattentive or impatient partner. Out of sync with the world around them, they have each lost something precious besides the obvious and are looking for a way to get it back. Kudo’s script largely drops the magical realism of the Taiwanese original with its strange world of talking lizards and opts for something a little less surreal if just as sweet while maintaining the borrowed time motif that suggests the universe is fair and willingly adjusts itself so that those who find themselves missing out will get that time back though there’s not a lot they can do with it other than reflect.

Even so within this miraculous dream space regrets can in a sense be cured and anxieties worked out. Those awake to stopped time have the opportunity to set things right, or at least to say their piece even if no one else can hear. There’s something more than time that they can recover, though it may be only small comfort and offer little more than one-sided closure. Rather than the Valentine’s Day setting of the Taiwanese original Kudo and Yamashita shift the action to the summer which with its many fireworks displays has a rather poignant quality focussed more on the loss than the rediscovery while emphasising the short-lived quality of human relationships which can nevertheless leave a warm afterglow even if the memory itself has been lost.

Setting the film in the historical city of Kyoto also adds to the magical feel, the emerging sunlight at one point appearing almost like a halo around the head of a frozen Hajime while he perhaps comes to accept his mother’s rationale that his father did not leave him but ran away from reality and ironically a world he felt he could not keep up with. In a repeated gag, Hajime calls up a requests show and pours his heart out to the host only for his mother to dial in and dispute everything he’s says especially reminding him that he’s not a loser but should slow down a bit and at least listen to the end of the conversation. Reika meanwhile might have to work herself up to speedier means of communication than the good old fashioned letter but can at least see that she gets there in the end even if it might take a little longer than for others.

Despite the differences between them, they are in fact perfectly in sync and just waiting for the times to align to bring them back together. Kudo and Yamashita lend their quirky romance a melancholy and heartwarming quality, steering clear of the awkwardness of the otherwise sweet and wholesome Taiwanese original in suggesting that the “date” at the film’s centre is the fulfilment of long forgotten promise rather than the momentary whim of a lovelorn romantic. Suggesting that the things you lose cycle back to you and that the universe itself is fair and kind, the film’s pure-hearted romanticism offers a hopeful reassurance that in the end it all really will work out for the best if only you give it time.

One Second Ahead, One Second Behind screens Nov. 4/5 as part of this year’s San Diego Asian Film Festival.

Original trailer (no subtitles)