Life is tough for the middle-aged man in contemporary Hong Kong, at least according to the directorial debut from screenwriter Sunny Chan, Men on the Dragon (逆流大叔). Economic woes, a precarious employment environment, familial strife, and elusive Andy Lau tickets all conspire to make our guys feel powerless in a society that seems primed to crush their spirits. Can dragon boating really help put their fire back in their bellies? Conventional wisdom would say no, but then there is something about physically demanding team sports that is particularly good at inflaming individual desires.

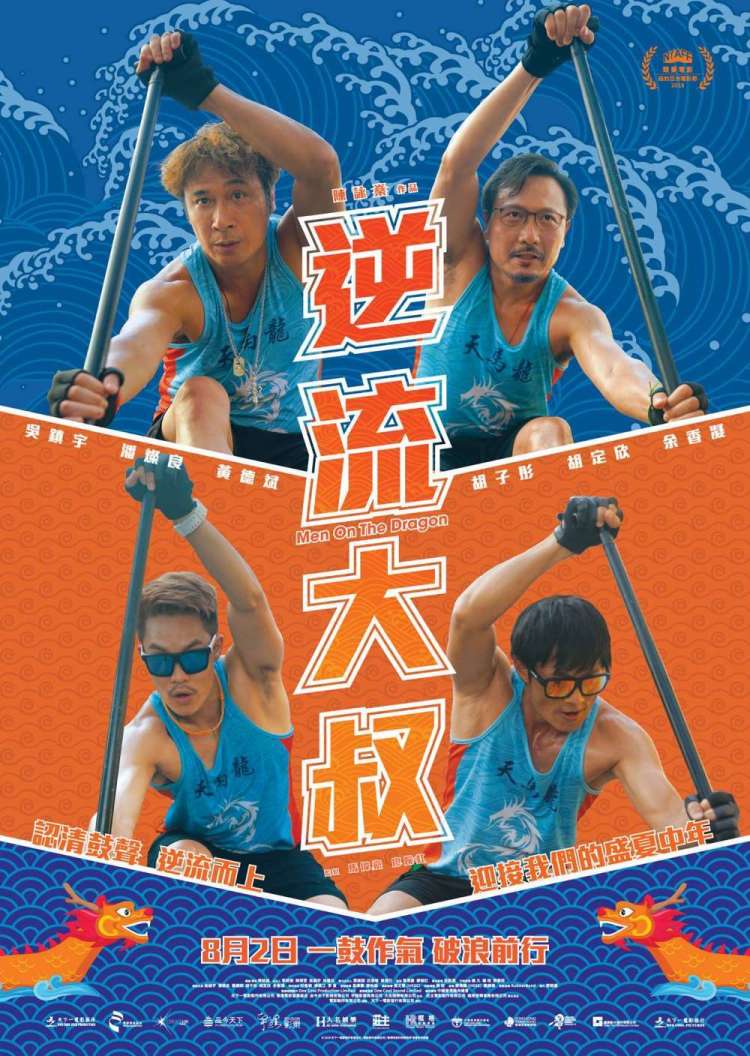

Life is tough for the middle-aged man in contemporary Hong Kong, at least according to the directorial debut from screenwriter Sunny Chan, Men on the Dragon (逆流大叔). Economic woes, a precarious employment environment, familial strife, and elusive Andy Lau tickets all conspire to make our guys feel powerless in a society that seems primed to crush their spirits. Can dragon boating really help put their fire back in their bellies? Conventional wisdom would say no, but then there is something about physically demanding team sports that is particularly good at inflaming individual desires.

Pegasus Broadband is about to announce another round of mass layoffs which has each of our heroes worried. Participating in a mini protest strike puts them straight in the firing line (even if they were clever enough not to write their real names on the petition forms), but when they’re seemingly lucky enough to escape the axe for now at least they think they can breathe easy. An unexpected call from the boss instructing them to appear at a mysterious location with swimming trunks in hand even has them wondering if they’re being given some kind of bribe to play nice but as it turns out the reverse is true. Pegasus Broadband wants to improve its public image and has decided to do that by entering a team in the upcoming dragon boat races. The race, which they fully expect to win, will be streamed live online to demonstrate the company’s infrastructural superiority. Fearing they’ll be bumped up the redundancy list if they refuse, our guys resign themselves to becoming unlikely dragon boat champions but end up discovering unexpected sides of their potential which prove essential in solving their individual crises.

Suk-yi (Poon Chan Leung), bespectacled and mild-mannered, is the least athletic of the Pegasus Broadband employees but is half grateful for the dragon boating opportunity because it gets him out of the house where his wife and mother constantly bicker while his small daughters can’t stop fighting. Feeling pushed out and unwelcome in his house full of angry women, Suk-yi is desperately looking for some kind of escape or possibility of reasserting his authority which he begins to find while training for the dragon boat races and nursing a small crush on the pretty coach, Dorothy (Jennifer Yu). Meanwhile, Lung (Francis Ng) is unmarried but has found himself in an awkward non-relationship with the woman next-door for whom he cooks and cleans, even taking care of her moody teenage daughter. He dreams of making a real family but lacks both the courage and financial resources to make a move. The youngest of the gang, William (Tony Wu), has the opposite problem in that he’s given up his dream of being a top Ping Pong player to build a future with his girlfriend but begins to realise that he hasn’t given up on his athletic hopes while boss Tai (Kenny Wang) is secretly torn apart by the worry that his wife is having an affair with a sleazy real estate agent.

All four guys have found themselves swept along by the current of modern Hong Kong, coasting without aim or purpose but filled with middle-aged anxiety as they wonder where the river is taking them and if it’s already too late to change the destination. Suk-yi’s dilemma is perhaps the most cliched of the three as he contemplates swapping his disharmonious household for the unattainable charms of an idealised younger woman while Lung chases easy familial bliss, Tai tries to repair a relationship corrupted by modern social pressures, and William wonders if it’s worth giving up a part of yourself to make a relationship work knowing that kernel of resentment will only grow with time. Men on the Dragon is, in this sense, a very “male” story in which four put upon men feel themselves emasculated by oppressive social forces yet learn to rediscover their “manhood” through the intensely physical act of dragon boating.

They are however guided along by an austere young woman who bangs the drum to which they must all march. This is not Dorothy’s story and she gets short shrift among all the guys but there’s something interesting in the fact that she had to hire a “male foreigner” to pretend to be the “real” coach because no one would hire a female dragon boater despite her impressive list of qualifications and credentials. Gently rebuffing Suk-yi’s interest, she nevertheless guides him towards a confrontation he’d long been avoiding in reasserting himself in his own household, restoring his standing in his wife’s eyes and brokering piece with his feisty mother who can’t seem to get on with her Mainland daughter-in-law. It’s the rhythm of life that’s important, Dorothy reminds the guys – you don’t get anywhere unless you’re all pulling together. That might sound like we’re back where we started, being swept along in a mass current without control or direction but it’s individual will which drives the communal enterprise and there can be no progress without agency. Not all dreams work out, but you won’t know unless you try and at least if you crash and burn there are plenty of guys waiting to pull you out of the water.

Men on the Dragon made its world premiere at the New York Asian Film Festival 2018.

Original trailer (English subtitles)