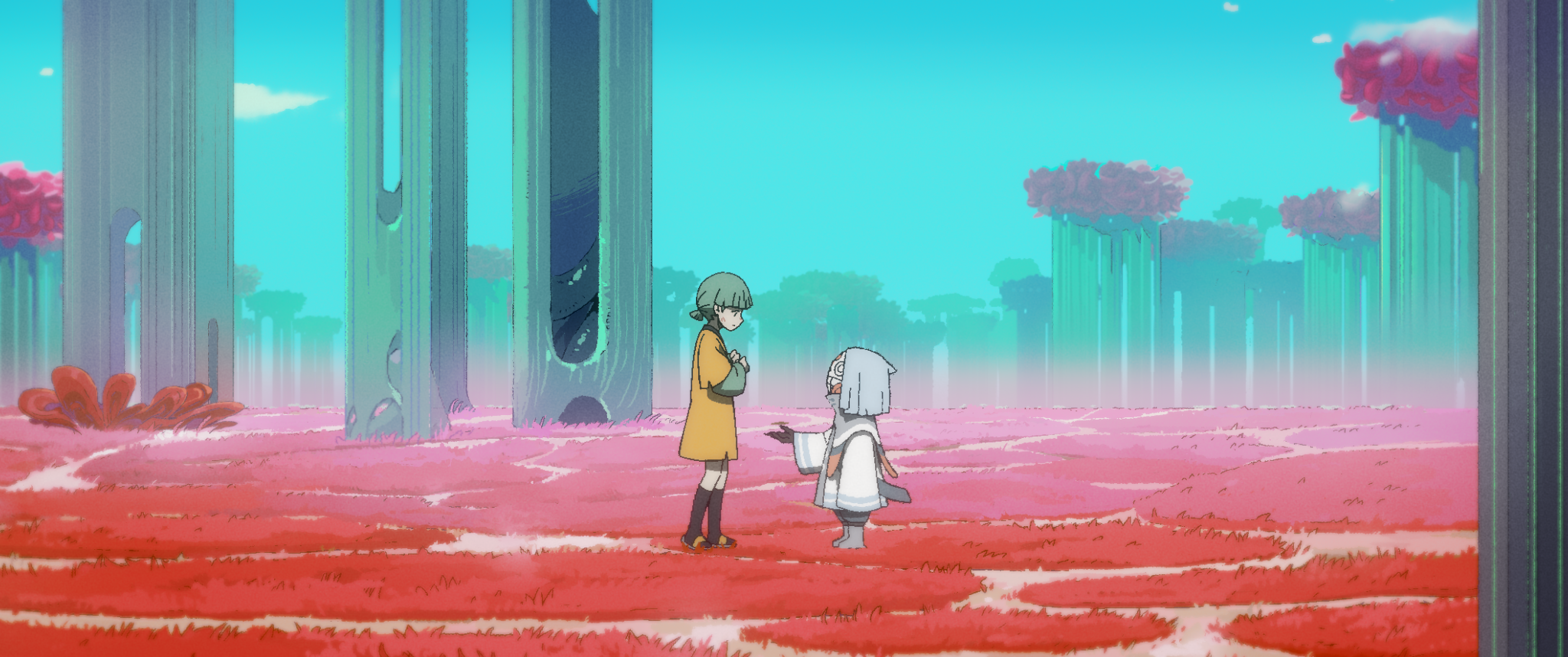

The Another World (世外) in title of Tommy Kai Chung Ng’s animated adaptation of Saijo Naka’s novel SENNENKI -Thousand-year Journey of an Oni-, most obviously refers to that beyond our own which belongs to the dead and those who exist outside of time, but it also hints at the other worlds that might be possible if only we could find ways to channel our negative emotions into something more positive rather than allowing ourselves to be consumed by rage and resentment.

As Soul Keeper Gudo (Chung Suet-ying) says, the seeds of evil lie within us all though he does not necessarily believe that they destroy humans, rather that they may also push us to survive. Throughout his wandering adventures, the souls he encounters are angry for reasons that are not irrational but a natural consequence of the world in which they live. Goran is a powerless princess resented by her subjects for being the apparent victim of a curse. She blames herself for her mother’s death in childbirth and is consumed by feelings of worthlessness even before her father the king dies and riddles the court with conspiracy. Coming to believe that he was murdered, her rage blossoms turning her into a cruel despot inflicting crazed violence on her subjects until eventually fleeing the palace. Flower City is reduced to Wheat Village where the farmers are pressed by the occupying force which demands half of their already poor harvest and does not much care if they starve to death despite warnings that they won’t eat either if the peasants are either too weak or too dead to farm the land.

It’s starvation that is really the true evil most particularly when it is caused or exacerbated by human greed and cruelty. Echoing Yuri (Christy Choi Hiu-Tung), a young girl who does not know she is dead and is intent on finding her brother from whom she has been separated, Gudo makes this simple act of sharing food a means of connection and identification. Farmer Keung, meanwhile, believes that he can only free the village by becoming a “Wrath”, a creature of indiscriminate violence that arises when the seeds of evil blossom and threatens to destabilise both this world and the other. Gudo tries to dissuade him, showing him that those who succumb to their rage and anger often end up harming those closest to them no matter how much they say they’ll be different. But Keung’s eventual conviction that their salvation lies solidarity and standing together against the oppressive regime eventually backfires when they’re betrayed by its duplicitous soldiers. Ying too, a young orphan exploited as child labour and forced to work in a factory during the Industrial Revolution, witnesses someone close to her literally consumed by the machinery.

The film does not suggest that this rage is wrong or misplaced, only that giving in to it is a choice that only puts more fear and evil out into the world. Gudo suggests the solution is solidarity after all in that anyone can offer salvation, but it also requires time and faith in one’s self. His various charges must learn to forgive themselves before they can let go, lay down their burdens and prepare for reincarnation. This is really the only way it is possible to endure this impossible world, which is not to say that it cannot be changed or resisted but that the means of resistance is to live in the better world that does not yet exist rather than succumb to violence which will result only in more of the same.

Beautifully animated, the film appears to draw inspiration from the work of Studio Ghibli including a few homages in particular to Castle in the Sky, though relying more on verbal exposition than purely visual storytelling or thematic resonance. Nevertheless, there is something satisfying in the depiction of resentments as a series of knots to be untied leading to a gradual liberation as if symbolising the work to be done. The closing scenes perhaps imply that this world cannot be cured, even if the other one may be, but is not itself without hope, and that whatever else may be human warmth and the desire for the world to be better will endure.

Another World opens in UK cinemas 29th February courtesy of Central City Media.

UK trailer (English subtitles)