Families, eh? Too much history, not enough past. In Aberdeen (香港仔), Pang Ho-cheung applies his cheeky magic to the family drama, taking a long hard look at an ordinary collection of “close” relatives each with individual secrets, lies, and hidden insecurities which could destroy the whole at any given second. Fishermen driven ashore by the tyranny of “progress”, these troubled souls will need to decide in which direction to swim – “home” towards sometimes uncertain comforts, or away towards who knows what.

Families, eh? Too much history, not enough past. In Aberdeen (香港仔), Pang Ho-cheung applies his cheeky magic to the family drama, taking a long hard look at an ordinary collection of “close” relatives each with individual secrets, lies, and hidden insecurities which could destroy the whole at any given second. Fishermen driven ashore by the tyranny of “progress”, these troubled souls will need to decide in which direction to swim – “home” towards sometimes uncertain comforts, or away towards who knows what.

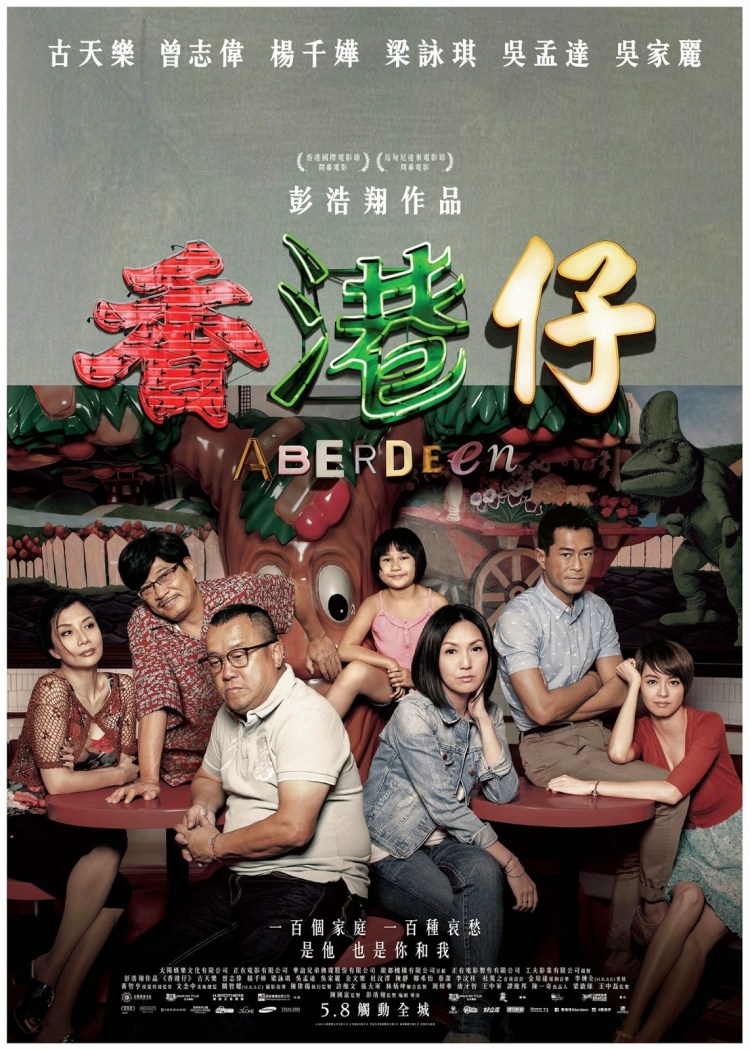

Grandpa Dong (Ng Man-tat), a Taoist priest, lost grandma a long time ago and is now in a relationship with Ta (Carrie Ng), a night club hostess. Dong’s son Tao (Louis Koo Tin-lok), a celebrity motivational speaker, does not entirely approve, feeling that the slightly taboo nature of Ta’s profession tarnishes his own veneer of glamour and may eventually cause him a public image crisis. Meanwhile, Tao’s wife Ceci’s (Gigi Leung Wing-kei) showbiz career is floundering now that she’s no longer as young as she was and she finds herself slipping into the seedier aspects of the business as her manager encourages her to “entertain” wealthy men to secure roles while her friend keeps inviting her to paid “parties”. Dong’s daughter, Wai-ching (Miriam Yeung), is married to a doctor, Yau (Eric Tsang Chi-wai), who unbeknownst to her is involved (unlikely as it seems) in a passionate affair with his nurse (Dada Chan) which she seems to think is more serious than it is.

Dong laments that his family can’t seem to stand being in the same room for more than a few seconds before someone ruins the whole thing with a stupid argument which might be a fairly common phenomenon in many families, but he worries that it’s all down to the fact that his ancestors were fishermen and now they’re paying for the bad karma of having killed all those fish. In fact, bad karma was one of the reasons his dad got him apprenticed to a relative who trained him up to be a Taoist priest so he could atone for generations of sin but it seems like the well ran far too deep.

Each of our protagonists is individually insecure, lacking the confidence that their family members truly accept them. Tao, vain and deeply cynical, doubts his daughter Chloe (Lee Man-kwai), whom he insists on calling “Piggy”, is really his because he thinks she isn’t very pretty and doesn’t fit with his slick, celebrity image. Nevertheless, he does love her deeply and worries that she will suffer in the long term through her lack of looks though this too is partly a self-centred projection stemming from long buried guilt over having bullied another “plain” girl while they were at school. He is also blind to the effect his constant references to Chloe’s supposed plainness are having on his wife, Ceci, who is carrying the scars of longterm insecurity regarding her appearance on top of the difficulties she is facing in her career.

Wai-ching’s problems run a little deeper in that she is convinced her mother stopped loving her after a slightly embarrassing childhood incident. The past literally returns to haunt her in the form of some paper offerings she made to her mother’s spirit which have been mysteriously sent back “return to sender” by the Hong Kong Post Office. Wai-ching’s mental instability seems to be a worry to her husband, but not so much so that he can’t just forget about it when his nurse comes calling with one of her cute little notes announcing that she’s in the mood.

Dong and Yau are in similar positions, each identifying with the figure of a beached whale – all washed up with nowhere else to go. As Dong puts it, as soon as you’re beached a part of you at least has died. Each of the older men has to accept that a choice has already been made and the energy needed to change it is no longer available. Pang allows each of the family members to find some kind of individual resolution, the family seemingly repaired as they chow down on generic fast food without making too much of a fuss, but then their solutions to their issues are paper thin and perhaps the family itself is merely the ribbon that flimsily binds an imperfectly wrapped gift that everyone has to pretend to like to avoid creating a scene. Still, sometimes the wrapping is the best part and it doesn’t do to go peeking inside lest you get a disappointing surprise.

Original trailer (English subtitles)