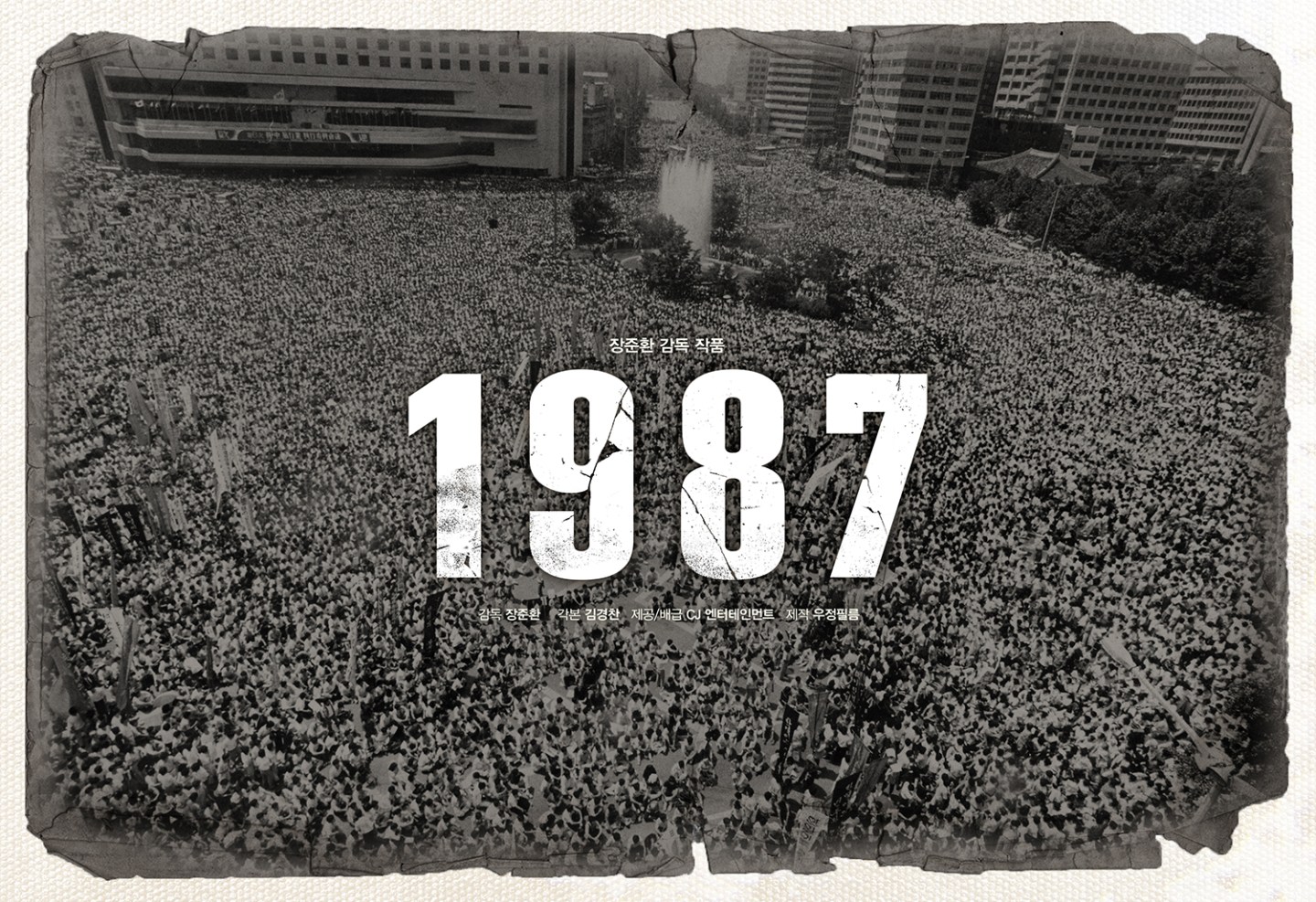

The political history of Korea is long and complex and oftentimes sad. The events depicted in 1987: When the Day Comes (1987), pivotal as they were, occurred just 30 years ago. Yet the recent past has also been one marked by protest, public anger, and political scandal though this time around with far less fear or danger. The protests of 1987 were a different story. The rule of Chun Doo-hwan, a military dictator who had seized power following the assassination of the previous dictator, Park Chung-hee, was one of extreme oppression which had already seen a widespread massacre of peaceful protestors by the state in Gwangju in 1980. Chun’s term, under the constitution, was set at seven years after which many hoped for a path to modern democracy but those hopes were dashed when he announced an intention to appoint his successor rather than call a free and fair election.

The political history of Korea is long and complex and oftentimes sad. The events depicted in 1987: When the Day Comes (1987), pivotal as they were, occurred just 30 years ago. Yet the recent past has also been one marked by protest, public anger, and political scandal though this time around with far less fear or danger. The protests of 1987 were a different story. The rule of Chun Doo-hwan, a military dictator who had seized power following the assassination of the previous dictator, Park Chung-hee, was one of extreme oppression which had already seen a widespread massacre of peaceful protestors by the state in Gwangju in 1980. Chun’s term, under the constitution, was set at seven years after which many hoped for a path to modern democracy but those hopes were dashed when he announced an intention to appoint his successor rather than call a free and fair election.

In depicting the climactic events of that summer, Jang Joon-hwan begins with chaos as a doctor is summoned to a mysterious room where a young man lies unconscious in a pool of water. The police have gone too far, and boy has died during interrogation. Aware of the potential danger of the public finding out that the state has in effect murdered a suspect in an act of torture, the head of the ACIB, Park (Kim Yun-seok), orders the body to be quickly cremated. This, however, needs a certificate signed by a prosecutor and Prosecutor Choi (Ha Jung-woo) is fed up with the ACIB and unwilling to cooperate especially as he smells a rat with the cause of death for a healthy 22-year-old listed as a “heart attack”. Not wanting to be on the wrong side of it if it does get out, Choi refuses the cremation and orders an autopsy which in itself triggers a series of other events eventually bringing the government to its knees.

The state remains cruel and duplicitous. The death of Park Jong-chul (Yeo Jin-goo) would become a catalyst and a rallying call, not just for the injustice of it but for the injustice of covering it up. Park’s family are denied their basic rights, his mother and sister literally dragged away from the morgue screaming while his traumatised father looks on in silent agony. They say that Park was a communist, that he died of fear because he weak while claiming all along to have done no wrong. Only when the “truth” begins to emerge does the ACIB decide to hang a few of its guys out to dry, urging them to “patriotically” take one for the team and head to prison for a while with a hefty compensation package to help sweeten the deal.

The death in custody becomes just one event in a situation spiralling out of control. Paranoid in the extreme, the Chun regime is also working on bringing down a “North Korean Spy Network” controlled by a democracy activist on the run who, unbeknownst to them, is also working with the Catholic Church who will eventually prove pivotal in delivering the truth to the people. Meanwhile, the press has also decided to jump ship, ignoring the government’s carefully crafted guidelines in favour of running actual news. Chun’s iron grip is slipping.

Jang’s biggest takeaway is that corrupt regimes crumble when enough people find the strength to go on saying no. It begins with Choi refusing to stamp a certificate then travels to the reporter who won’t back down, passes on to the secret revolutionaries bravely carrying messages at great personal costs, the not so secret clergy who perhaps have more protection to speak their minds (up to a point) than most, and of course the students in the streets who risked their lives to build a better future. One of the few completely fictional characters, the niece (Kim Tae-ri) of a prison guard (Yu Hae-jin) charged with conveying messages to an activist in hiding, proves the most illuminating in her inward struggle towards the democratisation movement. Afraid of the consequences and preferring to remain politically apathetic, she is eventually radicalised through witnessing the brutality of the regime first hand and suffering personal loss because of it.

Playing out as a taut thriller, 1987: When the Day Comes has a lived in authenticity from the motif of being constantly deprived of one shoe by a cruel and absurd regime to the deadly serious ridiculousness of men like Park who hate “the enemy” enough to destroy the thing they claim to love in pursuit of it. Timely and filled with melancholy nostalgia, Jang’s depiction of the pivotal events of 30 years ago is also a rallying cry in itself and an important reminder that the fight for justice is never truly won.

Screened at the 20th Udine Far East Film Festival.

International trailer (English subtitles)

2 comments