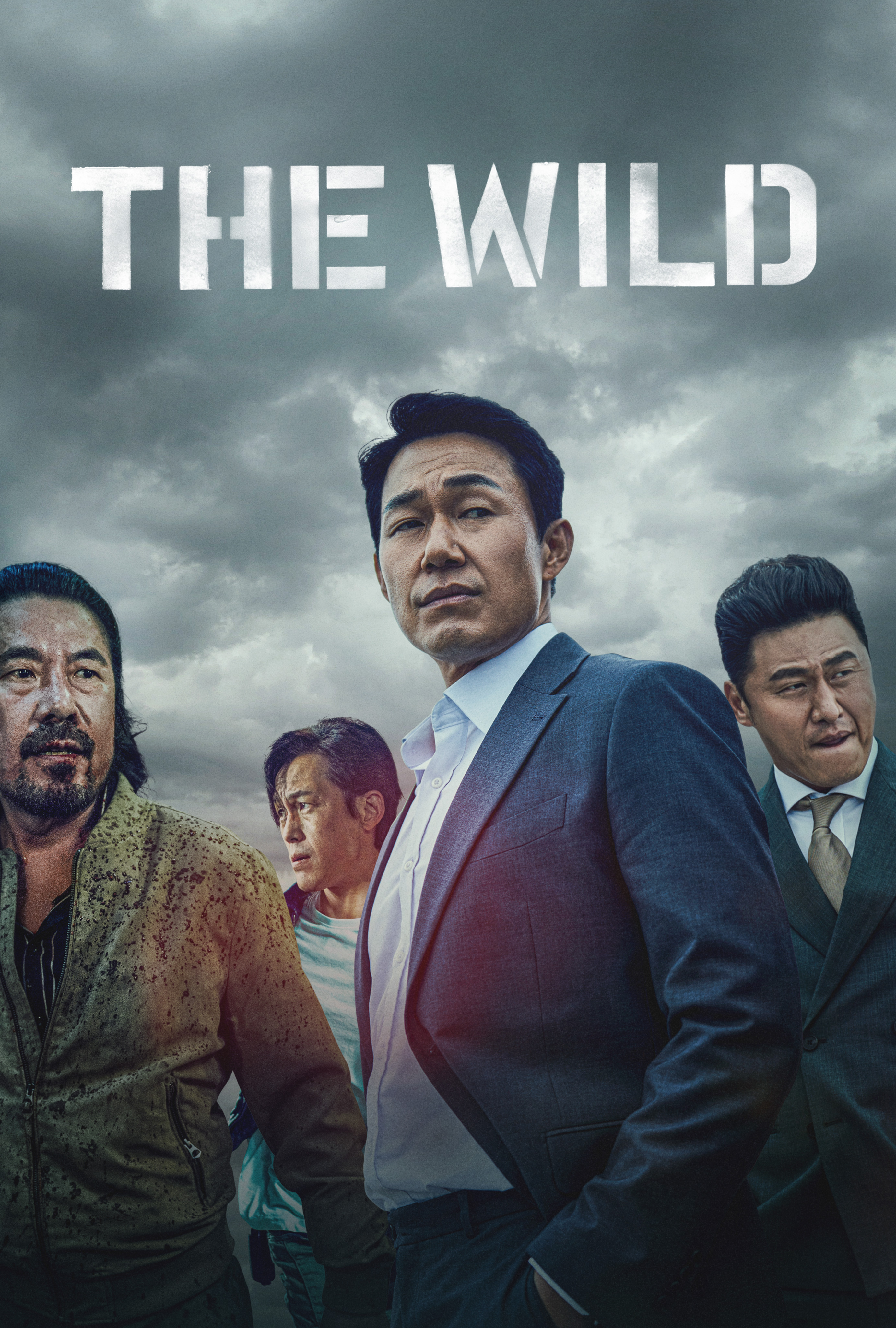

Who’s fault really is it? The hero of Kim Bong-han’s The Wild (더 와일드: 야수들의 전쟁, The Wild: Yasoodeului Jeonjaeng) goes to prison for seven years after the guy he was fighting in an illegal boxing match dies. But later he discovers that his friend and gang boss Do-sik (Oh Dae-Hwan) drugged his opponent first to assist in their match fixing scam, leaving a question mark about who was finally responsible for the young man’s death. It’s this confusing web of causality which damns each of the protagonists each in their own way seeking an impossible escape from the past.

The first thing that Woo-cheol (Park Sung-Woong) says when he gets out of prison is that he wants to lead a quiet life, refusing Do-sik’s offer to give him a bar in compensation for his long years inside. Yet Woo-cheol is quickly pulled back into the gangster underworld after bonding with a young sex worker, Myung-joo (Seo Ji-Hye), who also happens to be the former girlfriend of the man he killed. This brings him into conflict with corrupt cop Jeong-gon (Joo Suk-Tae) who is working with Do-sik to take out the middle man in their smuggling operation which is largely handled by North Korean defectors.

There may be something in the positioning of Gaku-su (Oh Dal-Su) and Woo-cheol as outsiders trapped by circumstance, yet the North Koreans otherwise depicted are all worst than the gangsters knowing only violence, recrimination, and rapaciousness. Putting up with them tries Woo-cheol’s patience and puts him at odds with Do-sik while disrupting the power play that has emerged between him and his underling Yoon-jae (Jung Soo-Kyo). Later in the film, another man calls them fools for being so obedient when the facts is that dogs never abandon their owners but are often abandoned by them. With so many concurrent schemes in motion, relationships are generally a weakness and it becomes impossible to know who can be trusted or what side anyone is on.

That’s a dilemma that strikes right at the heart of Myung-joo who is attracted to Woo-cheol’s manly nobility but also conflicted and later pursued by her late boyfriend’s younger brother who blames her for his brother’s death insisting that he only participated in the fight because he wanted money to move out so they could live together. Then again perhaps it was the mother’s fault for refusing him the money when he asked for it. Everything that happens is really everyone’s and no one’s fault, just a fatalistic motion towards an unstoppable end game. Do-sik prides himself on being able to make his own fate, but even he is carried along by forces outside of his control never quite as much in charge of his destiny as he’d like to think.

Meanwhile, he takes out his sense of futility on those around him. An intensely homosocial tale about the corrupted brotherhood between a series of men, the film has an unpleasant streak of deeply ingrained misogyny with strong depictions of sexualised violence and rape. Aside from Mrs Han, the feisty boss in charge of the girls who is later punished for her attempt to stand up to the men’s bad behaviour, the women are afforded little agency with Myung-joo reduced to little more than a tool used and manipulated by various plotters while like Woo-cheol longing to live a quiet life. Life him, she is dragged down by her guilt and trauma unable to escape her past. Do-sik, meanwhile, dreams of leaving this small-town world for the bright lights of Seoul but perhaps makes too great a calculation and finds himself outmanoeuvred by unexpected betrayal.

The film’s Korean title dubs the conflict between the men as a war between beasts, while it’s true enough that each of them is embroiled in a fiery hell preemptively looking for revenge before the threat has arisen. Romance and loyalty lead only to death and disappointment. A melancholy Do-sik asks Woo-cheol if they’re still friends and though it’s unclear if the question is genuine, seems to be harbouring a degree of regret in the coldness of his plotting either willing to sacrifice lifelong friendship or sure that those bonds are too secure to be broken. In any case, you cannot outrun fate nor find refuge from its ravages, only attempt to embrace its bitter ironies.

The Wild is available digitally in the US courtesy of Well Go USA.

International trailer (English subtitles)

Corruption has become a major theme in Korean cinema. Perhaps understandably given current events, but you’ll have to look hard to find anyone occupying a high level corporate, political, or judicial position who can be counted worthy of public trust in any Korean film from the democratic era. Cho Ui-seok’s Master (마스터) goes further than most in building its case higher and harder as its sleazy, heartless, conman of an antagonist casts himself onto the world stage as some kind of international megastar promising riches to the poor all the while planning to deprive them of what little they have. The forces which oppose him, cerebral cops from the financial fraud devision, may be committed to exposing his criminality but they aren’t above playing his game to do it.

Corruption has become a major theme in Korean cinema. Perhaps understandably given current events, but you’ll have to look hard to find anyone occupying a high level corporate, political, or judicial position who can be counted worthy of public trust in any Korean film from the democratic era. Cho Ui-seok’s Master (마스터) goes further than most in building its case higher and harder as its sleazy, heartless, conman of an antagonist casts himself onto the world stage as some kind of international megastar promising riches to the poor all the while planning to deprive them of what little they have. The forces which oppose him, cerebral cops from the financial fraud devision, may be committed to exposing his criminality but they aren’t above playing his game to do it. In 1925 an avid cave explorer, Floyd Collins, became trapped in a narrow crawl space. Though he was discovered and help came with food and water, a cave in left him sealed off down there and fourteen days later he died of thirst and exposure. As tragic as this obviously is, Floyd Collins is remembered for another reason – his rescue became one of the earliest mass media crazes. The surrounding media furore also inspired the 1951 Billy Wilder classic Ace in the Hole in which a grizzled reporter attempts to manipulate the fate of a man trapped in a cave for the maximum media coverage with the consequence that his delays cost the man his life. Jung-soo, a father on his way home with a birthday cake for his young daughter is about to join the marooned underground club when a shoddily built tunnel collapses sealing him inside. Unfortunately for Jung-soo, he finds that times have not changed all that much.

In 1925 an avid cave explorer, Floyd Collins, became trapped in a narrow crawl space. Though he was discovered and help came with food and water, a cave in left him sealed off down there and fourteen days later he died of thirst and exposure. As tragic as this obviously is, Floyd Collins is remembered for another reason – his rescue became one of the earliest mass media crazes. The surrounding media furore also inspired the 1951 Billy Wilder classic Ace in the Hole in which a grizzled reporter attempts to manipulate the fate of a man trapped in a cave for the maximum media coverage with the consequence that his delays cost the man his life. Jung-soo, a father on his way home with a birthday cake for his young daughter is about to join the marooned underground club when a shoddily built tunnel collapses sealing him inside. Unfortunately for Jung-soo, he finds that times have not changed all that much.