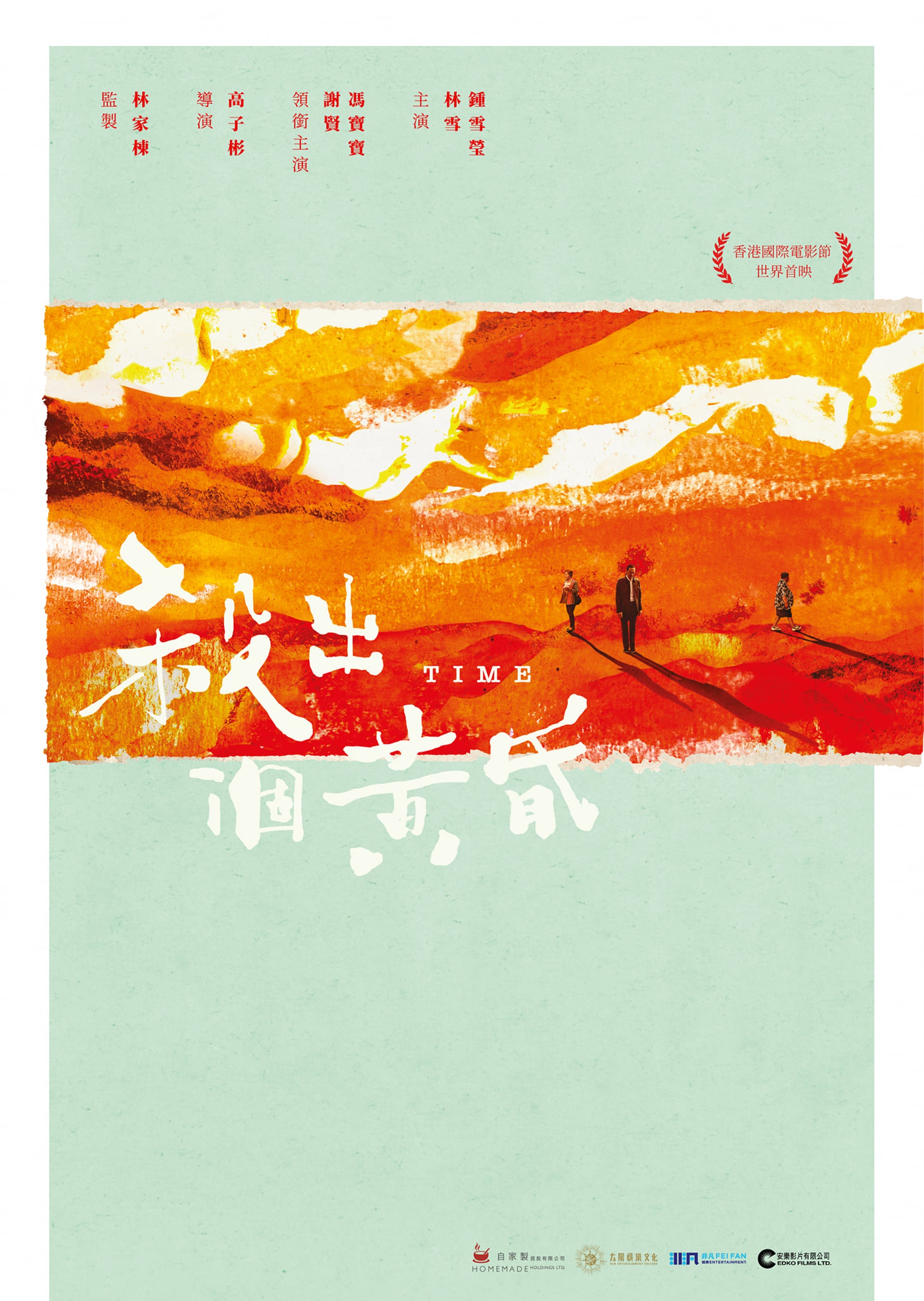

Youth is wasted on the young in Ricky Ko’s wistfully nostalgic ode to a bygone Hong Kong, Time (殺出個黃昏). Highlighting a series of very real social problems from the government’s failure to properly care for its old, to incurable loneliness, and the changing family dynamics of the modern society, Ko’s sometimes melancholy drama begins as a story about death but then finally becomes one about life granting its defeated heroes a second chance at a forgotten love in the formation of a new family.

Ko opens, however, with a kitsch retro sequence filmed in the manner of ‘70s action movies in which a trio of assassins cooly eliminate their targets. Flashing forward to the present day, hitman Chau (Patrick Tse Yin) is unceremoniously let go from his job as a noodle chef. Unable to keep up with the breakneck pace of contemporary Hong Kong, he’s being replaced by a machine. A message on a radio show brings him back into contact with his old gang, fixer Fung (Petrina Fung Bo-Bo) now a nightclub singer and owner of at the Golden Phoenix cabaret bar catering for elderly romantics, and getaway driver Chung (Lam Suet) who has formed an unwise emotional attachment to a sex worker he dreams of marrying. Fung has found them a new job, but Chau immediately senses something different on his arrival. His target is a bedridden old lady who’s called the hit on herself because she can’t afford the bills for her medical treatment and has no real quality of life.

Chau is so shocked he can’t go through with it, later seeing in a news report that the woman’s husband has been arrested in connection with her death. Her plight seems to have provoked a minor debate concerning lack of appropriate care for Hong Kong’s elderly. “Death is better than debt” is the way the woman’s husband characterised her choice, essentially affirming that there was no way for her to go on living in a society which has abandoned its elderly and infirm. Nevertheless, after that first case Chau takes on more requests for “euthanasia” from similarly afflicted people yet one of his most poignant is for a very wealthy man in good physical health who is simply lonely following the death of his wife. Though he had a large family, his children are far away with lives of their own and rarely visit. He chooses death in the hope of reuniting with his wife and escaping from the crushing loneliness of his existence.

One particular assignment, however, brings Chau into contact with vulnerable teenager Tsz-Ying (Chung Suet-Ying) who has been abandoned by her parents following their divorce and is currently living alone. Despite himself, Chau ends up taking the girl in and acting as her “grandpa” while she insists on learning his knife technique and how to make noodles the old fashioned way. For his part, Chau finds himself at odds with the modern world, confused beyond belief about how to pay for a bus ticket and embarrassed when a younger woman does it for him by waving her phone at a box by the driver. He stands rather than sit in one of the priority seats reserved for elderly passengers unwilling to accept that he has become old. Yet living with Tsz-Ying he begins to emerge into the modern society, learning how to use a smartphone and regaining something of his youth even as he bests a few young whippersnappers who made the mistake of underestimating an old guy.

While Chung, plagued by medical issues, quips that prison is “all inclusive” and you can get an appointment with your doctor any time you want, Fung has family issues of her own including a tense relationship with her snobbish daughter-in-law who’s determined to force her to sell her apartment and give up the club to get her grandson into an elite school. Despite their dark history as killers for hire, the trio are subject to the same problems faced by ordinary elderly people, witnessing lonely deaths and incurable pain coupled with a sense of futility which encourages them to think their lives are already over. Yet thanks to their involvement with Tsz-Ying they get a kind of second chance, building a new kind of family in intergenerational solidarity. Quirky and nostalgic, Ko’s aptly belated directorial debut feature may begin as a story about death and the inexorable march of time but finally makes the case for sidestepping the alienation of the modern society for a more wholesome sense of community and the eternal ability to start again no matter how old you are.

Time streams in the US Aug. 10 to 15 as part of this year’s New York Asian Film Festival.

Original trailer (English subtitles)

3 comments

Comments are closed.