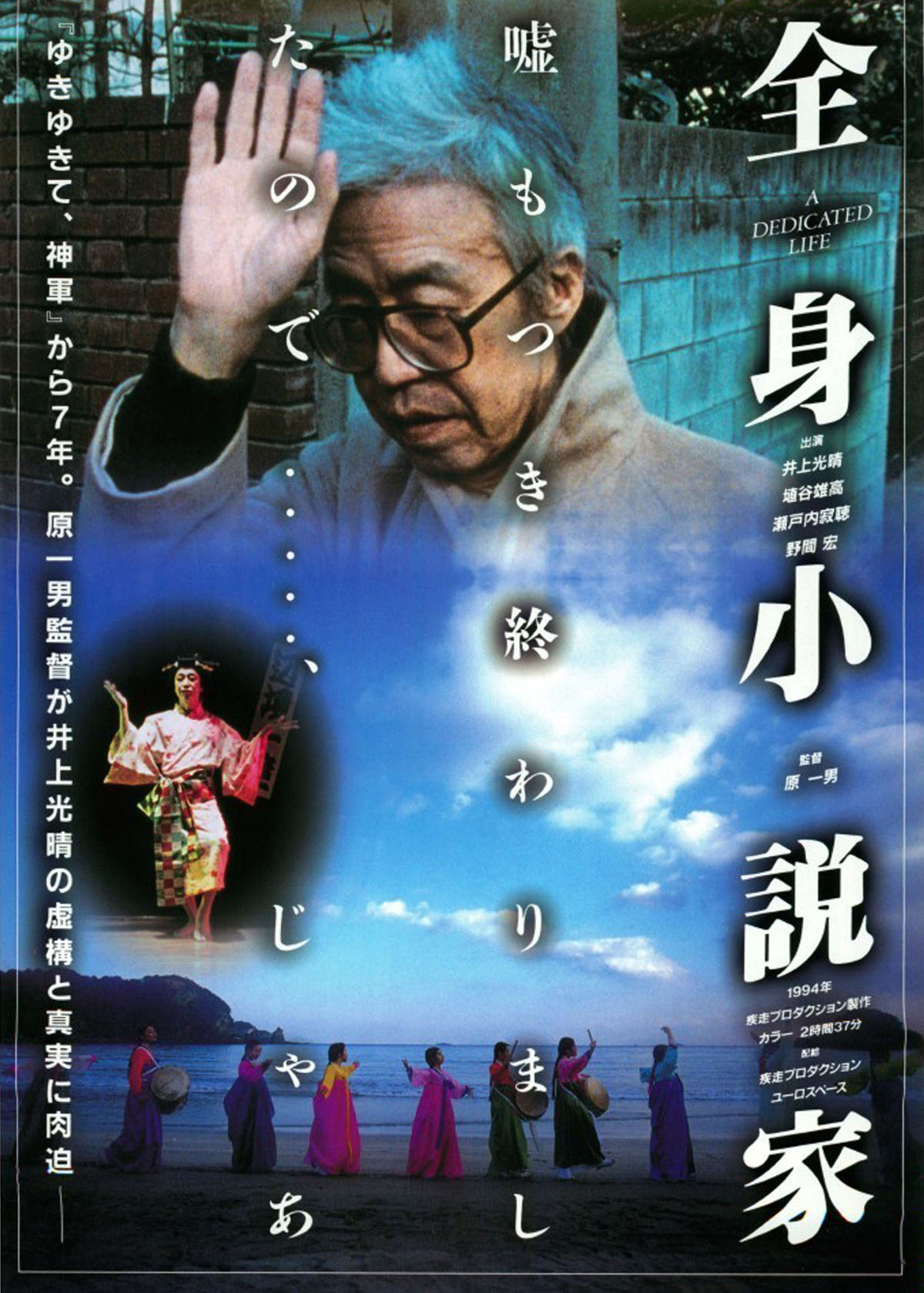

“Human beings have things they don’t want to share with others. This is the truth, but what we choose to tell from the truth is fiction” according to the elusive subject of Kazuo Hara’s probing personality doc, A Dedicated Life (全身小説家, Zenshin Shosetsuka). “Full of lies and contradictions” as a friend later describes him, Hara had apparently planned to follow controversial author Mitsuharu Inoue for a number of years only for his subject to be diagnosed with terminal liver cancer shortly after filming began.

Even as the film opens, however, we can intuit that much of the life of Mitsuharu Inoue is performance, an adoring audience of his students and followers screaming in pleasure as he performs a striptease while dressed as a geisha to the classic enka hit Tsugaru Kaikyo Fuyugeshiki. Seconds earlier he’d told them that he longed to belong to a theatre troupe and that his grandfather had been a famous kabuki actor, a claim that later seems to be entirely untrue. Nevertheless, Inoue commands almost cult-like adoration from the mainly middle-aged women who surround him, one after another confessing their undying love for the genius author in successive to camera interviews and only occasionally hurt or frustrated in the often callous way he seems to have treated each of them. As we later realise, somewhat casually, Inoue is also married to patient and presumably very understanding wife who tenderly cares for him throughout his illness.

To begin with, Hara presents us with a vision of Inoue at face value as a fun loving libertine living it up with his students/disciples who can also be cuttingly cruel in his criticism, humiliating one of his female followers at the podium by tearing apart her assignment in front of the class, later doing the same thing to a male author at a dinner party. After making a good recovery from his first battle with cancer he vows to go in harder with his students, reminding them that he can be friendly and charming one minute and unceremoniously cut them off the next should they disappoint him. Nevertheless, they apparently remain devoted to their mentor or at least the image of himself he seeks to project.

Those who’ve known him many years appear to know that Inoue is a habitual liar and that even his much praised autobiography is largely an act of autofiction. An author friend and Buddhist nun later suggests that Inoue perhaps had something deep inside him he didn’t want to share and lying was his way of taking control over his life, his cultivated persona an avant-garde literary act. Having presented him as he is or claims to be, Hara eventually begins to undercut Inoue’s image by interviewing friends, relatives, and acquaintances who frequently debunk his sometimes outlandish claims while also hinting at the half-truths and mysteries at the centre of his family history. Following Inoue’s sister Tazuko who remains as clueless as her brother realising they’ve either misremembered her grandmother’s name or it was wrong on the family register, Hara uncovers a melancholy tale of marital failure and maternal abandonment once again embellished by Inoue who alternately gives differing accounts of his youthful attempt to reconnect with the mother who left him behind which are themselves disputed by the recollections of others.

His grandiose claims go seemingly unexamined by his followers, eating up his tales of how he founded the first Communist Party in Japan only to become disillusioned by the movement and be kicked out after writing a story criticising the Party (a friend from the time describes him as more of an errand boy who was never really “serious” in his politics), or the tragedy of his first love which ended with a Korean classmate sold to a brothel where he later lost his virginity in a not quite consensual chain of events he claims left him feeling violated while she laughed from an upper window witnessing his defeated retreat. In a break from his usual observational shooting style, Hara adds a series of dramatic reconstructions tinted in a pre-war blue the unreality of which stands in stark contrast to the almost too intimate scenes of Inoue’s cancer diagnosis and subsequent operation as his liver is lifted from his belly and taken away as if presented for the camera. In a revealing moment, Inoue remarks that an alternative medical practitioner he’s just consulted going by the name “Redbeard” just like the movie is not convincing, lacking credibility because he failed to fill the gap between his words perhaps hinting at the techniques he himself uses to convince himself and others of his self-created image. Hara does not so much try to dissect it as to look quizzically at its contradictions, admiring the beauty of the enigma if in reflection of its intrinsic sadness.

A Dedicated Life streams in the US & Canada until July 2 as part of Japan Society New York’s Cinema as Struggle: The Films of Kazuo Hara & Sachiko Kobayashi

DVD rerelease trailer (no subtitles)

Sayuri Ishikawa’s Tsugaru Kaikyo Fuyugeshiki