Two women struggle with inter-generational conflict and the changing Taiwanese society in Huang Yu-Shan’s melancholy familial drama, Peony Birds (牡丹鳥, Mǔdan Niǎo). Perhaps the love birds of the title, mother and daughter find themselves at odds partly through a series of misunderstandings but also in the strange reversals of their social outlook, the older woman eventually becoming a successful industrialist rejecting the patriarchal social codes of her upbringing while the younger remains prudish and resentful, unfairly blaming her mother for her father’s early death.

The film opens with two children accidentally releasing a pair of caged birds before the camera lights on the melancholy figure of Ah-chuan (Su Ming-ming), absentmindedly embroidering beneath a large picture which appears to be of herself. The portrait, a source of contention with her husband Cheng, will follow her throughout her life a symbol of herself as a young woman with choices falling in hopeless love with a Japanese-speaking doctor, Kuo, who never gave her a second glance and later married someone else. Seemingly on the rebound, Ah-chuan consented to an arranged marriage to the wealthy son of a rice merchant who thinks himself a member of the local aristocracy, forever throwing around his money and reminding people of his good name, but the marriage is unhappy Cheng frustrated that his wife loves someone else and Ah-chuan unable to let go of her idealised image of Kuo. Soon enough, Cheng drowns, falling into the river stumbling around in a drunken stupor. As they pull his body out of the water, doting daughter Shu-chin remembers her father bitterly exclaiming that her mother loved someone else and, noticing the comforting arm of childhood friend Chin-shui on her shoulder, assumes it must be him.

It’s this fundamental misunderstanding that continues to colour the frustrated relationship between the two women, the grown-up Shu-chin (Vivian Chen Te-Yung) childishly complaining that Ah-chuan failed in her wifely responsibilities and has never been a mother to her, blaming her for Cheng’s death while criticising her commitment to her career almost as a betrayal of womanhood. By this point, Shu-chin is in her 20s and has a job as a record producer, later attempting to push her mother towards retirement claiming her salary is enough to support both her and her artistic brother but eventually leaving home entirely after beginning an affair with an unsuitable man defiantly ignoring Ah-chuan’s attempts to convince her she is making a huge mistake.

Meanwhile, Chin-shui resurfaces in their lives having become a wealthy real estate magnate, a career we saw him start back in the village by taking advantage of the post-war land reforms to buy up the redistributed estates of formerly noble families, some of it Cheng’s. In some ways, former sharecropper Chin-shui is a villainous Lopakhin intent on paving over the beautiful Taiwanese countryside with towering high rise buildings, a symbol of the nation’s transformation from agrarian economy to financial powerhouse and of the hollowness it implies. Yet Ah-chuan’s business is floundering partly she claims because of protectionist US trade laws leaving her at the mercy of men like Chin-shui who, though not the man in her heart, has long carried a torch for her despite knowing of her impossible, unrequited love for Dr. Kuo. Shu-chin finds herself in a similar position in her affair with free-spirited colleague Li Kang whose previous girlfriend attempted to take her own life, discovering the mutability of his affections after he becomes famous with one of his solo compositions, while also drawn to a more suitable match in the more traditional Yi-cheng who eventually pledges his love to her, offering to make her a home explaining that having a home is what gives the young confidence to wander.

Yet “home” is what Shu-chin continually rejects, yearning for her childhood in a more rural, quasi-feudal Taiwan while misunderstanding the tragedy of her parents’ toxic romance, only latterly reawakening to her mother’s love for her and discovering a new sense of security in a changing Taiwan as Ah-chuan frees them both in literally setting fire to the frustrated hopes of the past, reminding her “It’s always been our home”. A touching story of two women finally coming to understand each other while learning how to live in a changing society, Huang Yu-Shan’s maternal drama eventually bridges a generational divide as mother and daughter finally flee the coop but choose to fly together.

Peony Birds streams in the UK 25th to 31st October as part of this year’s Taiwan Film Festival Edinburgh.

Clip (English subtitles)

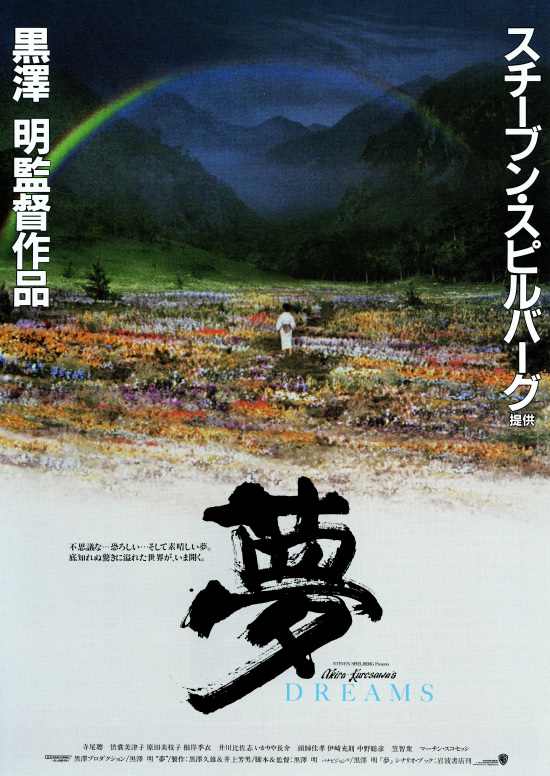

You might think there could be no more diametrically opposed directors than Akira Kurosawa – best known for his naturalistic (by jidaigeki standards anyway) three hour epic Seven Samurai, and Nobuhiko Obayashi whose madcap, psychedelic, horror musical Hausu continues to over shadow a far less strange career than might be expected. However,

You might think there could be no more diametrically opposed directors than Akira Kurosawa – best known for his naturalistic (by jidaigeki standards anyway) three hour epic Seven Samurai, and Nobuhiko Obayashi whose madcap, psychedelic, horror musical Hausu continues to over shadow a far less strange career than might be expected. However,  Despite a long and hugely successful career which saw him feted as the man who’d put Japanese cinema on the international map, Akira Kurosawa’s fortunes took a tumble in the late ‘60s with an ill fated attempt to break into Hollywood. Tora! Tora! Tora! was to be a landmark film collaboration detailing the attack on Pearl Harbour from both the American and Japanese sides with Kurosawa directing the Japanese half, and an American director handling the English language content. However, the American director was not someone the prestigious caliber of David Lean as Kurosawa had hoped and his script was constantly picked apart and reduced.

Despite a long and hugely successful career which saw him feted as the man who’d put Japanese cinema on the international map, Akira Kurosawa’s fortunes took a tumble in the late ‘60s with an ill fated attempt to break into Hollywood. Tora! Tora! Tora! was to be a landmark film collaboration detailing the attack on Pearl Harbour from both the American and Japanese sides with Kurosawa directing the Japanese half, and an American director handling the English language content. However, the American director was not someone the prestigious caliber of David Lean as Kurosawa had hoped and his script was constantly picked apart and reduced.