“We, all of us, can be heroes! Let’s support each other to beat this monster.” the hero of Shunji Iwai’s pandemic dramedy, The 12 Day Tale of the Monster that Died in 8 (8日で死んだ怪獣の12日の物語, Yoka de Shinda Kaiju no Juninichi no Monogatari) affirms. Inspired by Shinji Higuchi’s Kaiju Defeat Covid project and originally streamed as a web series, Iwai’s surreal screen drama is replete with the atmosphere of the pandemic’s early days, a mix of boredom and intense anxiety coupled with a determination to protect and support each other through this difficult time. Yet it’s also a tale of uncanny irony taking place in world in which Ultraseven is a documentary while the Earth has apparently been subject to waves of monster aggression, alien visitors, and even apparently an epidemic of ghosts.

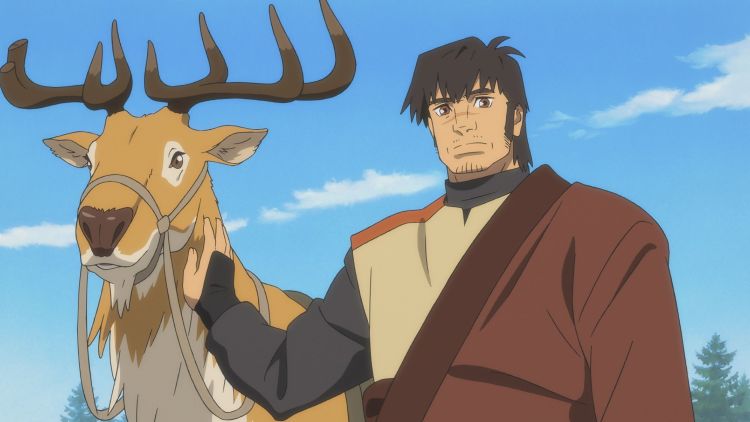

All of this the hero, Takumi Sato (Takumi Saitoh playing a version of himself) finds out from director Shinji Higuchi after contacting him on Zoom for advice about how to raise the “Capsule Kaiju” he bought on the internet in order to do something to help battle corona virus. Sato’s single “egg” soon becomes three, later back down to one again causing him to worry if the other two managed to escape or perhaps were eaten by the sole remaining monster. In any case, while they are three he names each of them after various Covid-fighting drugs and is informed by Higuchi that they currently resemble three kaiju from classic tokusatsu series Ultraseven.

Nevertheless, Takumi is continually confused and disappointed by the slow progress of his project, confessing to one of his friends online that they were rated only one star on the store he bought them from but he’s sure that’s just because they’re a new product. His friend Non, (also playing a version of herself), meanwhile, has invested in an alien though the alien is, conveniently enough, entirely invisible and inaudible via camera. Non’s alien seems to be making much better progress to the extent that it eventually becomes disillusioned with selfish, apathetic human society and decides to return to outer space. Challenged, Takumi has to admit he hasn’t really done anything to make the world a better place except for raising his capsule kaiju and even that hasn’t gone particularly well.

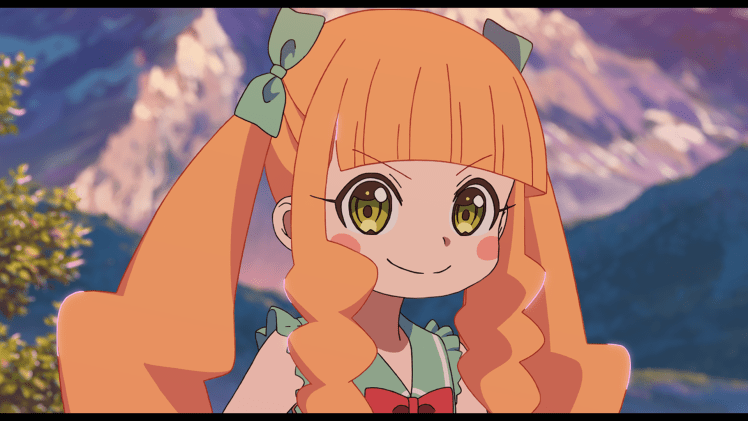

Then again, perhaps just getting through is enough to be going along with in the middle of a global pandemic. Takumi’s friend So (So Takei) is separated from his family in Bangkok and is struggling to find work as a chef while all the restaurants are closed only to later confess that he actually has a second family he, understandably, had not mentioned before in Japan that he also needs to support financially. Even so, Takumi is bemused watching the YouTube channel of a young woman (Moeka Hoshi) who broadcasts from her bathtub dressed in a nightgown and has managed to raise a recognisably dragon-like kaiju while his keep shapeshifting without progressing into a final form. He starts to worry, what if his kaiju are actually evil and intend to destroy the world rather than save it? The fact that it eventually takes on the form of a giant coronavirus might suggest he has a point, but kaiju work in mysterious ways and perhaps they are trying to help in their own small ways even if it might not seem like it in the beginning.

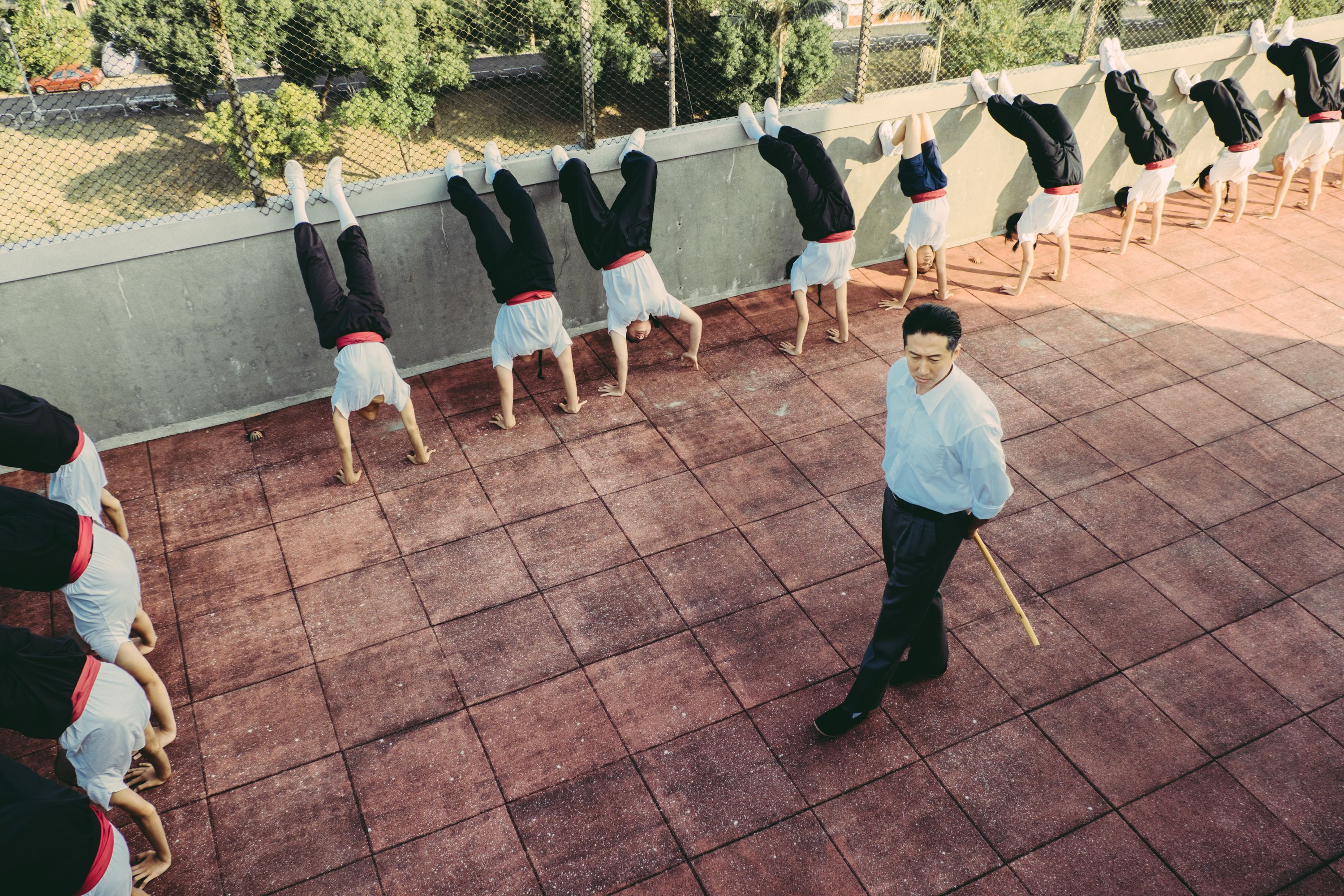

In many ways that might be the primary lesson of the pandemic, everyone is doing their best even if they’re only doing something small like staying at home and wearing their mask. Shot entirely in black and white and mostly as direct to camera YouTube-style monologues or split-screen Zoom calls complete with occasional lag and echoing, Iwai adds in eerie pillow shots from a camera positioned high above the streets of a strangely quiet but not entirely empty Tokyo along with fragmentary dance sequences of young women dressed in black with CGI kaiju heads. A whimsical slice of pandemic life, 12 Day Tale ends as it began, with Takumi once again reminding us that we are all heroes and should support each other to beat the “virus monster” but adds a much needed note of hope as he assures his audience that the the day we beat the virus will certainly come, “let’s do our best together”.

The 12 Day Tale of the Monster that Died in 8 streams in Canada until Aug. 25 as part of this year’s Fantasia International Film Festival.

Original trailer (English subtitles)