“It’s been a while since I asked, who are you?” comes the incongruous question at the beginning of Kosuke Nakahama’s stylish, hugely accomplished graduation movie B/B. What begins as an unconventional, reverse investigation of a bizarre crime committed in a bizarre world, eventually descends into a philosophical interrogation of the modern society and most particularly its continued indifference. “All the oppressors and all the oppressed, those who didn’t notice the pain. We’re all complicit. You think you’re the exception?” asks the witness of her questioners, partly perhaps in justification but also pointing the finger back at a society which prefers to avoid asking uncomfortable questions.

Set in an alternate 2020 in which the Olympics has been suspended not because of a global pandemic but because of a bribery and corruption scandal, and a terrorist gas attack by a shady cult has recently been foiled, the central mystery revolves around the murder of a convenience store manager dubbed by some the “Icarus” killing. Sana (Karen), a high school girl, has been called in as a person of interest because of her connection with the victim’s son Shiro (Koshin Nakazawa) who has become withdrawn and is unable to offer testimony of his own. The problem is that it’s not exactly “Sana” that they want to talk to as the young woman apparently suffers from Dissociative Identity Disorder, once known as multiple personality. A cynical policeman and sympathetic psychiatrist have been tasked with trying to sort out her unreliable narrative to discover her connection with the crime.

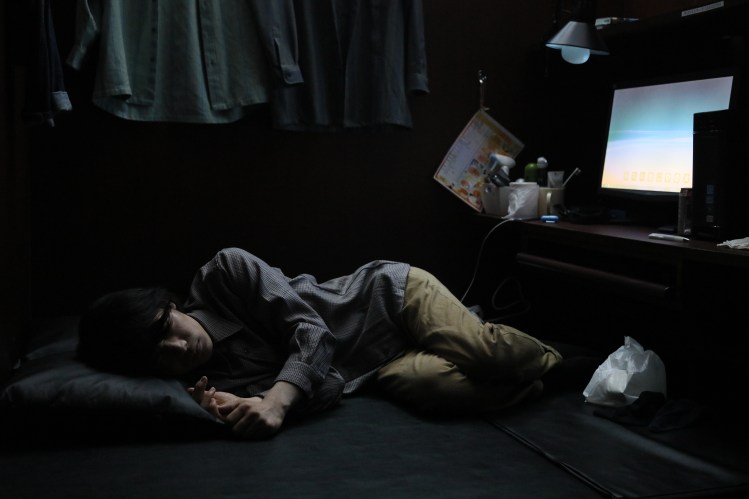

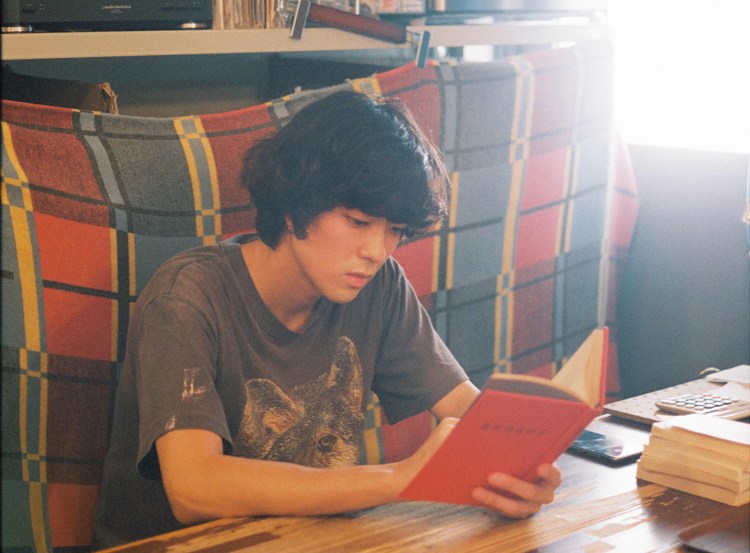

In a handy piece of symbolism, Sana apparently hosts 12 distinct personalities, a perfect inner jury, while the body of the murdered man was apparently dismembered into 12 parts. As the psychiatrist later advances, the personalities are a symptom of Sana’s mental fracturing in response to trauma and were not born altogether but arrived individually following the increasingly traumatic events of her life presumably beginning with her mother’s death. It’s this sense of parental abandonment that allows her to bond with Shiro who, like her, avoids school by hanging out in local parks in his case because of a further sense of rejection in realising that his teachers are aware of the abuse he suffers at home, Sana immediately noticing the scars protruding from the collar and sleeves of his T-shirt, but have chosen to do nothing to protect him.

The goal is not to unlock the mystery of Sana, to cure her or to address the various traumas which lie at the root of her psychological fracturing but to investigate the Icarus murder. She is not, however, a credible witness. An infinitely unreliable narrator, her personalities switch at random each giving their own contradictory testimonies in their characteristic fashion. Nakahama mimics Sana’s mania through frantic cutting and abrupt edits, close ups on hands, feet or random objects rather than faces or landscapes. The earliest scenes with Sana and her posse of imaginary friends, only six of whom she is apparently able to manifest at one time, hanging out in the park are shot with a beautiful summer glow coloured with its own kind of nostalgia as she slowly befriends Shiro bonding in shared trauma and a mutual sense of safety.

While the interrogation scenes trapped in the relative claustrophobia of the doctor’s office may have a sense of the clinical, the judicial manifests most clear in Sana’s mind. The “Council of Sages” in which all her personalities are present takes place in a minimalist space of black and white, shot like a Renaissance painting with echoes of the The Last Supper, as they crowd around and wonder what’s to be done about the Shiro problem, the manic pace slowing somewhat as Sana’s thoughts apparently clear. Yet as she later says to the disbelieving policeman pointing out the absurdity of prosecuting crimes committed as opposed to preventing those yet to occur, “This is hell, we are all trapped in hell”, advancing that she does not believe someone from hell belongs in heaven and would rather reign below than live in pitiable servitude above. Anchored by a phenomenally strong performance by Karen, sophisticated fast paced dialogue including more than a few surprisingly retro pop culture references, and featuring stylish on screen text Nakahama’s striking debut ultimately takes aim at societal indifference and perhaps points the finger at the viewer to pay more attention in a world of constant suffering.

B/B screened as part of the 2021 Osaka Asian Film Festival.

Original trailer (no subtitles)