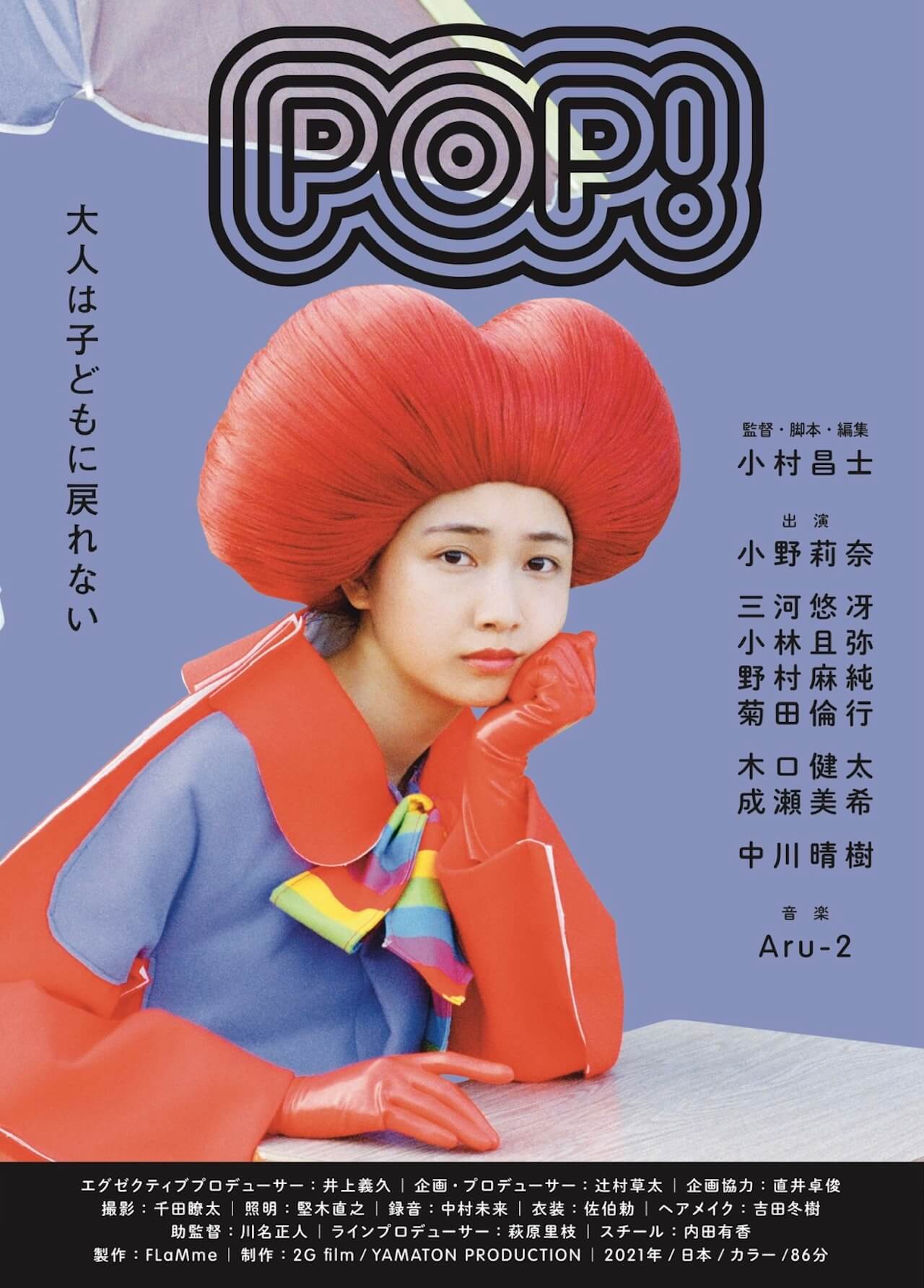

You’ve heard “turn that frown upside down”, but are you ready for turn that heart into a…well, perhaps that’s a sentence not worth finishing. The heroine of Masashi Komura’s MOOSIC LAB venture Pop! finds herself in a world of existential confusion on realising that what she assumed to be a heart symbolising love was in fact a giant bum intended to moon an indifferent society. Suddenly she doesn’t know up from down, her entire existence rocked as she contemplates life, love, and the pursuit of happiness on the eve of her 20th birthday.

19-year-old Rin (Rina Ono) is currently the presenter/mascot character of local TV charity program “Tomorrow’s Earth Donation” which aims to collect money for the world’s disadvantaged children. Meanwhile, she also has a part-time job as a car park attendant which she takes incredibly seriously even though almost no one ever turns up (including her mysterious co-worker Mr. Numata). In fact, its Rin’s earnestness and youthful naivety which seem to set her apart from her colleagues, makeup artist Maiko later complaining that she makes others uncomfortable with her goody two-shoes act while her bashful present to puppeteer Shoji on his birthday of a framed portrait she’d drawn of him seems to elicit only confusion and mild embarrassment from her bantering co-workers.

Nevertheless, she’s beginning to wonder about love, in her own way lonely and unfulfilled simultaneously confused and disappointed by the direction of her life. She dreamed of becoming an actress, but is now little more than a front for this strange enterprise in which she, characteristically, believes with her whole heart. Deep down, she just wants everyone to be happy and is sure that if people smiled more the world would be a brighter place. Wearing a giant red wig shaped like a heart, she reads out messages purporting to be from children outlining their dreams for the future even when they’re as banal and materialistic as wanting to become a race car driver. Unfortunately, however, she continually stumbles when asked to read a cue card featuring her own dream, fully scripted for the character she’s supposed to be playing.

On her first audition, she was shouted out of the room by a director insisting her admittedly over the top improvised death scene was nothing more than attention seeking. The TV news attributes a similar motive to a mysterious bomber currently plaguing the city whom Rin accidentally witnesses one day fleeing the scene of his crime. For some reason struck by his strange presence, and perhaps disillusioned with her brief foray into online dating, Rin develops a fondness for him believing he is just like her because the pattern of his bombings corresponds to the shape of a giant heart enveloping the city. “We must get serious about saving the world!” she announces to her colleagues, “Let’s do it with a bang!” she ironically adds. She may, however, have slightly misunderstood his mission statement especially as when questioned as to his motives he tells her that he does it for the benefit of all because no one else will.

In any case, she remains hopelessly naive, confused by a strange man who brings his van to the car park presumably for “privacy” and strangely unconcerned by an alarming message on an abandoned car left with its door open which states the driver won’t be needing it anymore. She role-plays direction and agency, but in the end goes nowhere until literally carried away by her “adult” realisation that it’s probably not possible for everyone to smile all the time and it’s not her job to make them. Caught up in the slightly duplicitous world of the cynical program makers who perhaps mean well but are hamstrung by the problems of contemporary Japan, desperate for pictures of smiling children only to realise that none are writing in and hardly any of them know any to ask, she maintains her desire for world peace even while privately conflicted in having lost sight of her own dream. Adopting a little of the bomber’s anarchist swagger, she allows herself to be swept up by a final flight of fancy towards a more cheerful world. Shot with a colourful “pop” aesthetic and a hearty slice of absurdist irony Komura’s strange fairytale is stuffed full of heart and has only infinite sympathy for its earnest heroine’s guileless goodness.

POP! screened as part of the 2021 Osaka Asian Film Festival.

Original trailer (no subtitles)