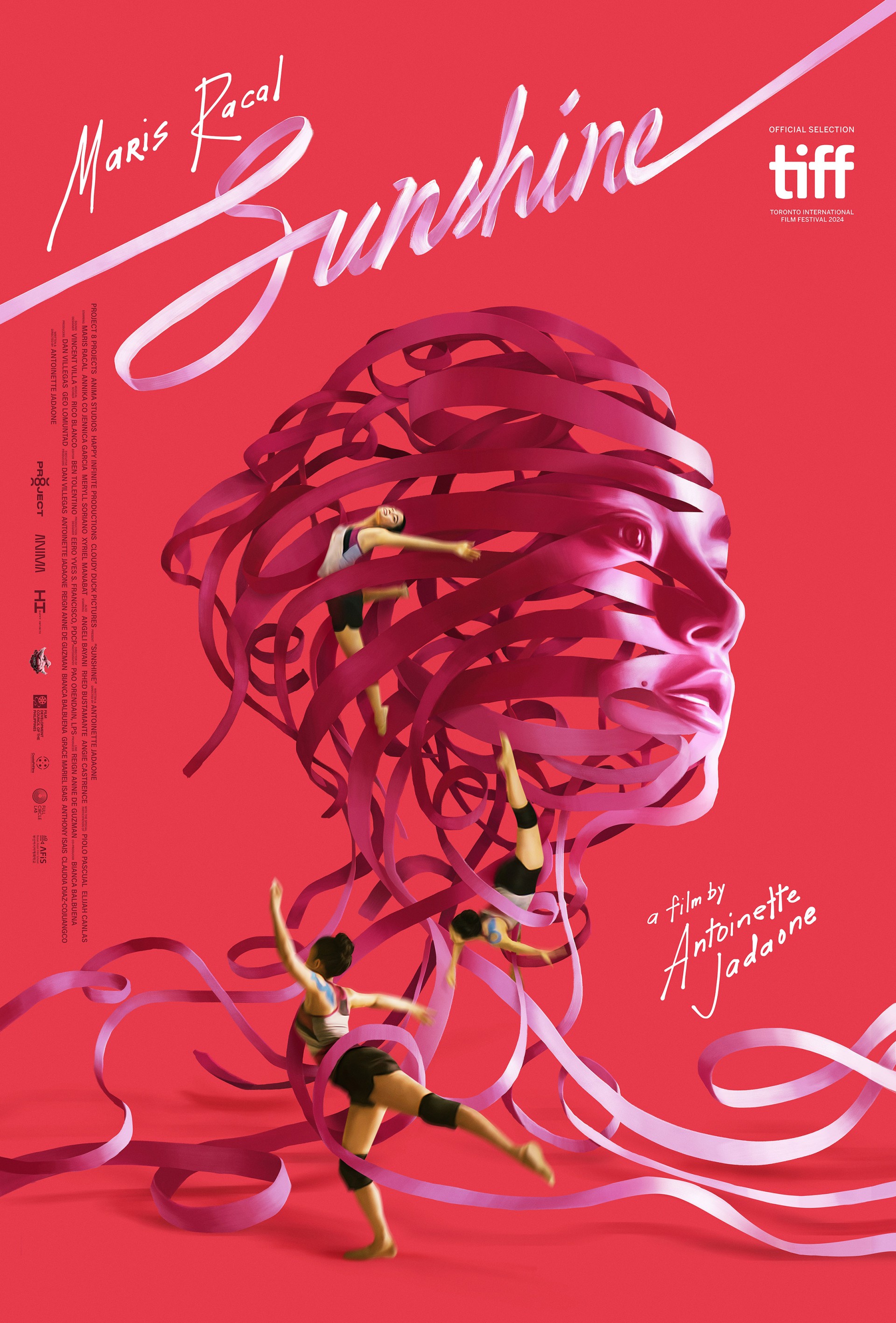

“Don’t drag me into this,” a boy says after hearing that his girlfriend is pregnant, having already questioned if the baby’s really his. Miggy signals his lack of responsibility by directly asking Sunshine what “her” plan is, making it plain that she’s on her own and he does not see himself playing an active role in a predicament he essentially sees as nothing to do with him. Aside from Miggy’s father Jaime, who happens to be a protestant pastor, men are largely absent from Antoinette Jadaone’s Sunshine and even when they appear rigid figures of patriarchal control.

Sunshine implies that she’s only in this mess because Miggy pressured her into unprotected sex, but she’s left to deal with the fallout on her own. Still in school, she’s about to take her last shot at getting onto the Olympic rhythmic gymnastic team but risks losing everything she’s worked so hard for if her pregnancy is discovered. Even when she goes to buy a pregnancy test, she’s asked for ID and judged by the woman behind the counter while it’s otherwise true that abortion is illegal in all circumstances in the Philippines, meaning Sunshine’s only options are finding and paying a wise woman for medicine to provoke a miscarriage.

It’s the reactions of other women that Sunshine most fears from her otherwise supportive coach, whose ambitions also rest on her performance, to her best friend who does in fact shun her on her mother’s insistence, and her older sister who is caring for the whole family and seems to be a single mother herself having had a baby at a young age. Like a grim siren, Sunshine’s niece won’t stop crying as if echoing the alarm of her impending maternity and her own discomfort with it. It’s a network of women that she turns to for solutions if not for advice. There’s no one Sunshine can ask for that, because what she’s looking for is illegal. All she can do is stand outside the church and pray that God take mercy on her by allowing her to wake up from this nightmare. There’s something quite ironic when she’s told to ask forgiveness from God “the father” by a religious and judgemental female doctor as if laying bare the patriarchal and oppressive underpinnings of the entire society.

Yet cast onto a surreal odyssey through Manila in search of solutions, Sunshine finds herself becoming the supportive presence she herself doesn’t have. While pursued by a very judgmental little girl who echoes her inner confusion by branding her a “murderer” and questions her decision making, Sunshine is approached by another little girl who appears to be heavily pregnant and is begging for money to see a faith healer whom she hopes will help her end her pregnancy. Despite her own experience, Sunshine asks her why she doesn’t ask her boyfriend for help but the girl explains that he’s not her boyfriend, he’s her uncle, so she’s even more powerless and alone than Sunshine is. No one’s going to do anything about the Uncle Bobots of the world, but they’re only too happy to criminalise and abandon a little with no one else to turn to.

Realising that the girl was trying to abort her child, the male doctor at the hospital refuses to treat her knowing full well there is a possibility she may die. Only a sympathetic female doctor is later willing to help. Sunshine too almost dies after her first attempt at taking an abortion pill which she does all alone at a love hotel where the woman on the counter didn’t want to give her a room because people who go to hotels on their own are a high risk for suicide. When she does eventually find out, Sunshine’s sister is actually sympathetic and stands up to Jaime on her behalf when he makes a bid to take over her life and force her into maternity by getting Miggy to apologise and unconvincingly insist that he actually loves her and their baby while leveraging his wealth and privilege against her by recommending that she be cared for by his family doctor and the best hospitals at his expense. It does however provoke a degree of clarity in Sunshine’s insistence that she doesn’t want to be a mother and has no intention of becoming one while rediscovering herself in rhythmic gymnastics and making peace with her younger self. A sometimes bleak picture of young womanhood in the contemporary Philippines, the film nevertheless finds relief in pockets of female solidarity and the conviction that it doesn’t have to be this way for the younger generation who should be free to pursue their dreams and make their own choices about what they do with their bodies.

Sunshine screens April 26 & 30 as part of this year’s San Diego Asian Film Festival Spring Showcase.