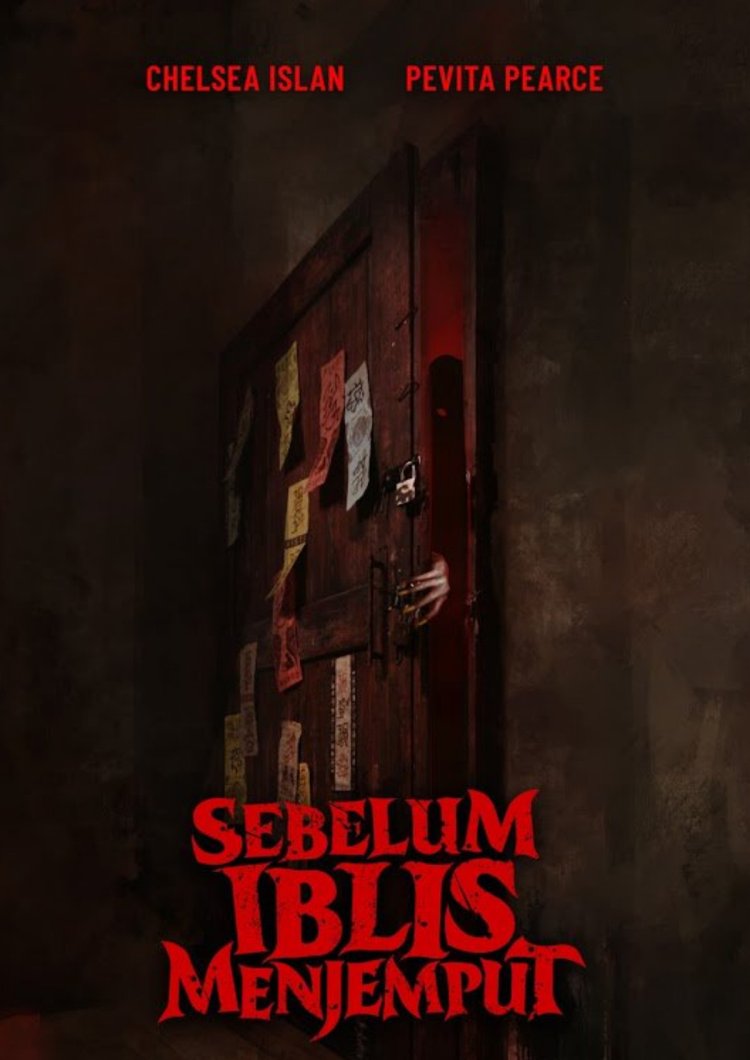

Top travel tip – if you encounter a door which is plastered with Buddhist sutras, it’s generally a very bad idea to open it. In this case, just not opening the door is a valid and very sensible option. Sadly, it’s one the protagonists of Timo Tjahjanto’s May the Devil Take You (Sebelum Iblis Menjemput) decided not to take. Following Joko Anwar’s Satan’s Slaves, May the Devil Take You also has a few hard questions to ask about the nature of “family” and how strong those bonds really are when the supernatural presses on already exposed nerves.

Top travel tip – if you encounter a door which is plastered with Buddhist sutras, it’s generally a very bad idea to open it. In this case, just not opening the door is a valid and very sensible option. Sadly, it’s one the protagonists of Timo Tjahjanto’s May the Devil Take You (Sebelum Iblis Menjemput) decided not to take. Following Joko Anwar’s Satan’s Slaves, May the Devil Take You also has a few hard questions to ask about the nature of “family” and how strong those bonds really are when the supernatural presses on already exposed nerves.

The film opens with formerly successful property entrepreneur Lesmana (Ray Sahetapy) entering some kind of agreement with a demonic shamaness whom he later kills and hides in the basement of his remote country villa. An undisclosed amount of time later, Lesmana is struck down with a mystery illness which forces his fractured family back together. Alfie (Chelsea Islan), Lesman’s estranged daughter from his first marriage, is called back to the bedside along with her step-siblings Ruben (Samo Rafael) and Maya (Pevita Pearce), famous actress step-mother Laksmi (Karina Suwandhi), and half-sister Nara (Hadijah Shahab). Forced politeness eventually gives way to resentment, especially when Laksmi begins to ponder selling the villa which is technically in Alfie’s name even if still thought of as a “family” property. When everybody unexpectedly turns up at the same time in search of things of value, they have very little idea of what it is that awaits them there.

Once again the threat is a bad inheritance in which the children are forced to pay for the crimes of their “father” who has let greed get the better of him and allied with dark supernatural forces in order to make himself fabulously wealthy. Lesmana’s sensational success is less due to his business acumen than to selling his soul, well not actually “his” but those belonging to his loved ones, to the Devil. His business empire apparently in tatters, Lesmana has both a problem and a solution, but the Devil is always wanting more and there may lines Lesmana won’t cross even when he is apparently willing to sacrifice the lives his wife and children just to be accounted a “success”.

There may be horrors lurking in the cellar of every home, but in this one they are quite literal and very, very angry. Family, as a concept, is the weapon the Devil chooses to wield, poking into all the dark and uncomfortable corners that basic civility usually leads most to avoid. Alfie, angry and carrying the trauma of her mother’s death, is resentful of her father’s new family and most particularly of her imperious step-mother whom even Maya later describes as “not a good person”. Yet for all that she can’t quite bring herself to “hate” her step-siblings, especially the kindly Ruben who seems to have embraced his role as a natural peacemaker. Their bonds will be tested by insidious evil which presses hard on their insecurities of their awkward family set-up in which no-one quite feels accepted, or wanted, or loved by almost anyone else.

Then again, family itself becomes a source of salvation when the buried past is unearthed and then reburied having been properly dealt with. Rather than a comment of Lesmana’s rejection of traditional religion and misuse of black magic, May the Devil Take You is an exploration in the desperation of a greedy man whose desire for infinite instant gratification is matched only by the Devil himself. Lesmana was willing to sell his family for gold only to change his mind and lose them anyway. The supernatural horror is all too real, but rooted in the sins of the father and in the broken familial connections which continue trap each of the protagonists in the stereotypically creepy remote rural mansion complete with creaking floorboards and leaky ceilings. Tjahjanto’s awkward tone, over-reliant on genre norms to degree of parody but distinctly serious, makes for a strangely uneven experience but there is certainly enough hellish imagery to fuel the nightmares of many a susceptible viewer.

Screened at the 2018 BFI London Film Festival.

Original trailer (no subtitles)