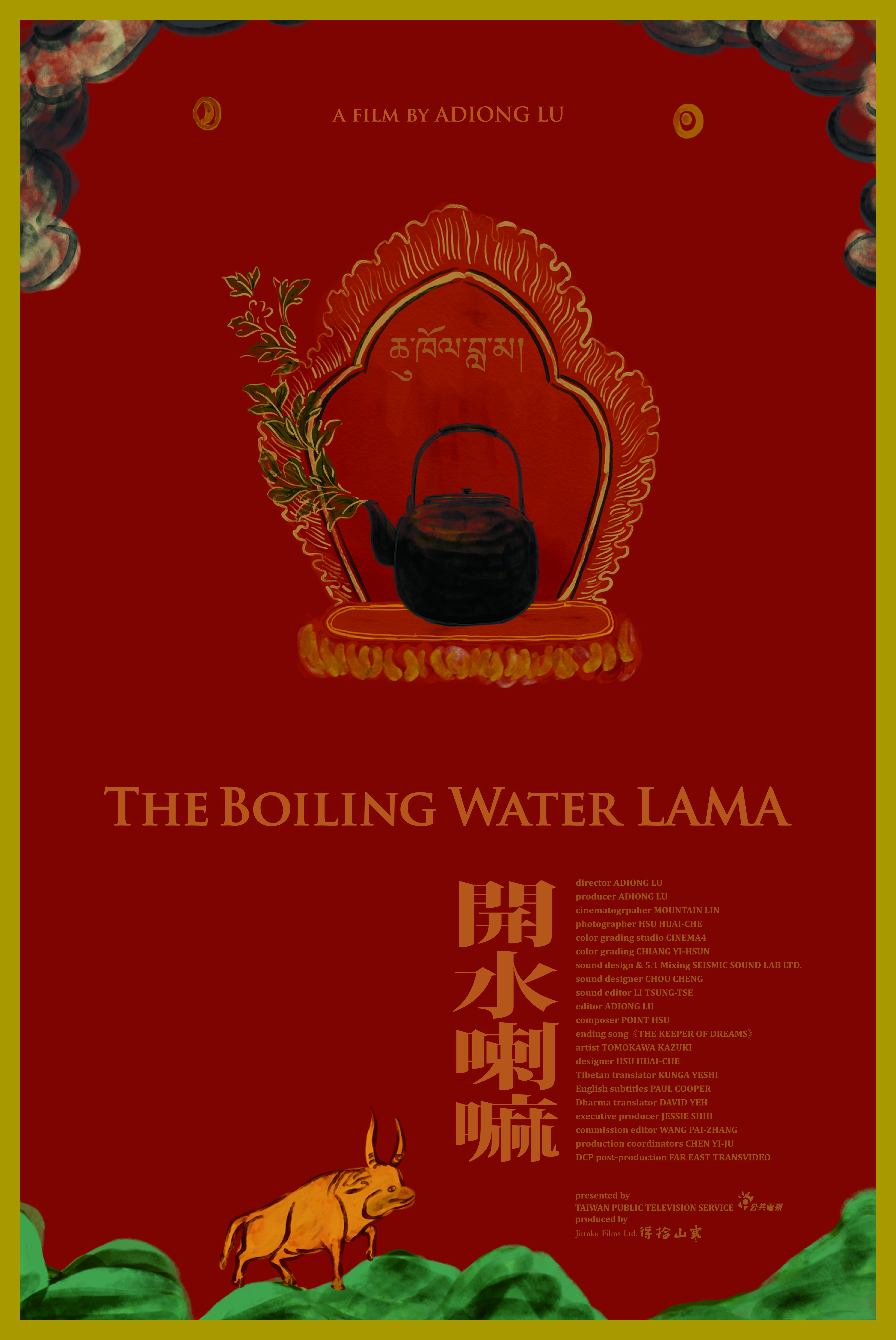

A lone monk provides spiritual healing in a decaying world in Lu Adiong’s enigmatic documentary Boiling Water Lama (開水喇嘛, Kāishuǐ Lǎma). Living in wooden house built by his followers high up in the small village of Xiongtuo on the Tibetan plateau, the Lama provides both pastoral care and traditional medicine to residents of the region many of whom have travelled over the mountains to visit him in hope of gaining his wisdom.

Lu opens however with a lengthy shot of the desolate landscape, frosty and seemingly devoid of human presence home only to mud, smoke, and rubble. Later he will cut to a series of similar shots featuring a family of wild boar encroaching into the village, seemingly free to roam as if nature is already reclaiming this crumbling settlement. The Lama meanwhile remains hidden to us, crammed in as we are with a tightly packed group of followers awaiting his advice in a darkened room alight only with the warm yellow glow of the surrounding walls. The problems they bring him are many and varied, often related to the process of death and dying wanting to know which sutras they should read for a late relative, or intensely curious to know when and where their deceased loved one might have been reborn. Perhaps because of the obvious demands on his time, the Lama’s replies are often curt, imbued with unexpected efficiency as he simply consults his charts and recommends an appropriate sutra. He does not appear to recognise his visitors even when they remind him that he himself oversaw a ritual for them sometime previously, though he is always patient and kind, pausing to give a small boy receiving medical treatment some pocket money to buy sweets on the way home.

Meanwhile, he also treats the sick attaching suction cups to the affected area to suck out the “bad blood” while explaining to another complainant that his problem is he is like a car engine with not enough oil and too much petrol. Cauterising the wound with incense sticks, he completes his treatment by spitting boiling water over the broken skin, handing over some paperwork to the husband which he apparently does not need to return in person. Other callers meanwhile are burdened with emotional dilemmas, a man wanting advice about the marriage of two village youngsters who’ve fallen in love but the girl’s parents aren’t keen and in any case would prefer that she and her new husband live independently rather than with his family as the in-laws wish. The Lama does not give the man the answer he was perhaps hoping for nor does he have a very favourable prognosis for another who visits wanting to know if it’s in the cards for him to patch things up with the wife who’s apparently left to return to her parents though as he tells it not because there was anything wrong in their relationship.

True to his name, the Lama keeps the kettle boiling while a collection of visitors gather outside his home waiting for the climactic purification ritual in which men and women remove their shirts and endure the scalding water on their bodies, some directing it to the site of their ailments, baring their knees or ankles. Others have brought their children who scream in pain and terror, the water clearly far too hot for them to bear while the Lama spits out the last of the boiling liquid into the eyes of those there afflicted. In contrast to the traditional setting, many of the villagers can be seen photographing or filming the event on their smartphones to record the occasion. As if to refute the final image, however, of the Lama overseeing the landscape as the villagers return home, Lu breaks the intense Japanese folksong playing over the end credits with a whimsical, snow covered scene in which a cow eventually appears and fixes its gaze directly into the camera lens. An enigmatic exploration of a disappearing way of life in all of its various contradictions, Boiling Water Lama finds no answers to its central questions leaving only the Lama as he metes out his judgements to all who come seeking his advice.

Boiling Water Lama screens on 12th December at London’s Rio Cinema as part of Taiwan Film Festival UK 2020.

Original trailer (English subtitles)