A struggling influencer’s bid for internet fame through marrying herself soon goes dangerously awry in Kiwi Chow’s anarchic take on contemporary social media mores and the need for authenticity, Say I Do to Me (人婚禮). Ping (real life YouTuber Sabrina Ng Ping) swears that she’s done with changing herself for others and is determined to enjoy life on her own terms, but the irony is she’s anything but honest with herself as she attempts to bury her abandonment issues and ambivalence towards marriage beneath her friendly clown persona.

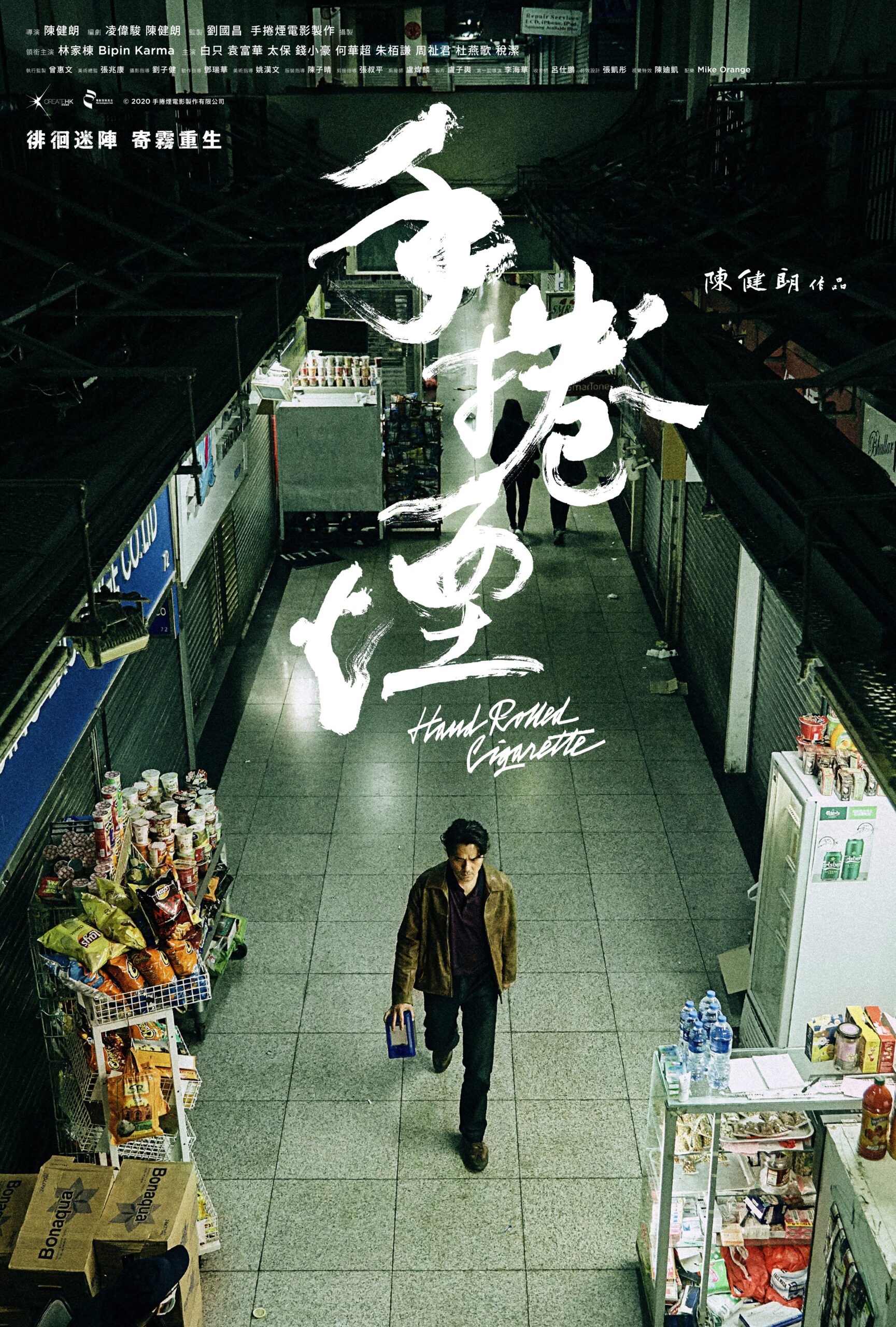

Despite telling all her followers that she sees no need to wait around for someone else to make her happy so she’s going to marry herself, Ping is in a longterm relationship with middle-school sweetheart Dickson (Hand Rolled Cigarette director Chan Kin-long) who handles the tech side of their YouTube channel. When their clown-themed videos failed to win an audience or pay the bills they started looking for something edgier, shifting their focus to their own relationship. When that too failed to set netizen’s hearts aflame, they started engineering fake romantic drama including a “real fake” wedding and Dickson cheating scandal. To get themselves out of the hole they’d dug, Ping comes up with the idea of “sologamy” in which she’ll get back at “cheating” Dickson with a solo wedding on the day they would have got married, while Dickson mounts a counter campaign wearing a giant monkey head to promote his “solo funeral” movement railing against fake affirmation of Ping’s embrace of “authenticity”.

Of course, authenticity is the one thing Ping isn’t selling. She’s telling everyone else they should be true to themselves, but has based the whole thing on a lie in still being in a relationship with Dickson while adopting a fake influencer persona of a woman who has herself together and is fully ready for commitment. The duplicity begins to eat away at her as she witnesses its effects on others including a middle-aged woman (Candy Lo Hau-Yam) she’d assumed to be in a perfect marriage who suddenly reveals she’s been unhappy for decades because she couldn’t accept her sexuality. Thanks to Ping, she’s decided to divorce her husband and live a more authentic life all of which leaves Ping with very mixed feelings. Meanwhile, she’s relentlessly pursued by a devoutly religious man who seems to be in love with her on spiritual level, and also comes to the attention of “Hong Kong’s last Prince Charming” who has hidden anxieties of his own.

The film seems to ask if it really matters if Ping was “lying” when her example has made a “positive” difference in people’s lives in enabling to them to accept themselves and find true happiness even if in doing so they might necessarily hurt someone close to them. Dickson seems certain that the internet isn’t really real and you really don’t need to be “authentic” in your online persona, but is all too quickly addicted to the false affirmation of likes and shares and willing to compromise himself morally to get them, all while justifying his actions in insisting he’s only doing it to make Ping’s dreams come true. In the end, he is also playing a role for Ping but as she says coopting her dreams as his own just as her other suitors do. “No one here cares how I feel” she declares, realising her “fake” persona has become a kind of prop for others to hang their unfulfilled desires on.

The problem is only compounded by the reckless actions of the solo funeral crew who quickly escape from Dickson’s control demonstrating the dark side of internet tribalism and accidental radicalisation. But Ping’s own worst enemy is herself, afraid to really look in the mirror and face her insecurity while simultaneously peddling the message that everyone’s lives will improve as long as they make a superficial gesture of self-love. What she discovers during a surprisingly violent cake fight, is that she’s not the only one battling internal insecurity to become her authentic self and there might be something in “sologamy” after all if it forces to you to confront the parts of yourself you don’t like and accept them too. Part absurdist treatise on the corrupting qualities of online validation and part surreal rom-com, Chow’s quirky comedy nevertheless comes around to its heartwarming message in allowing its heroine to make peace with herself and the world around her.

Say I Do to Me is in UK cinemas now courtesy of Haven Productions.

Original trailer (Traditional Chinese / English subtitles)