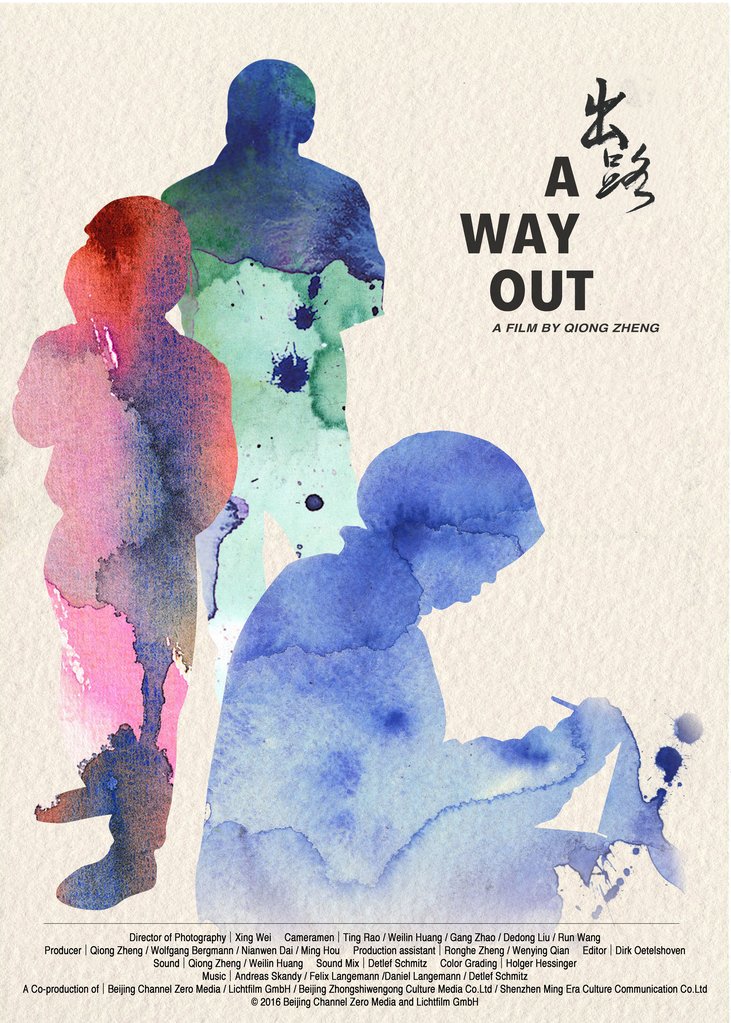

The duplicitous dichotomies of the modern China have become a permanent fixture in the nation’s cinema though mostly as a symbol of conflicted ideologies as some yearn for a return to an imagined past egalitarianism and others merely for a brake on the runaway train of capitalist materialism. Zheng Qiong’s documentary A Way Out (出路, Chūlù) follows the lives of three youngsters chasing the “Chinese Dream” albeit in their own particular ways only to discover that, in the end, despite the best intentions of those who might seek to lessen the advantages of privilege, birth may be the biggest factor in deciding one’s destiny.

The duplicitous dichotomies of the modern China have become a permanent fixture in the nation’s cinema though mostly as a symbol of conflicted ideologies as some yearn for a return to an imagined past egalitarianism and others merely for a brake on the runaway train of capitalist materialism. Zheng Qiong’s documentary A Way Out (出路, Chūlù) follows the lives of three youngsters chasing the “Chinese Dream” albeit in their own particular ways only to discover that, in the end, despite the best intentions of those who might seek to lessen the advantages of privilege, birth may be the biggest factor in deciding one’s destiny.

Zheng opens with a little girl, Ma Baijuan, in rural Gansu. Her sing-song voice playing over her cheerful stride to school through the narrow mountain paths hints at a natural curiosity, a desire to know the “why” of everything, but Baijuan is only reciting by rote what it is says in her school book. Her education, which is received at a village school segregated by sex where she is one of only two little girls learning simple facts about the world around her while the boys next-door get a crash course in elementary maths, is largely a matter of questions and answers rather than thought or enquiry. Nevertheless, she excitedly tells us that she will soon be going on to the middle school in the nearest town and then hopefully to a college in Beijing after which she will make a lot of money and buy a new house for her family with a proper well so they can get water.

Meanwhile, 19-year-old Xu Jia has already repeated the final year of high school twice in the hope of bettering his exam grades to get into a good university. Like many of his contemporaries, Xu sees a degree from a reputable institution as the only “way out” of small town poverty. He is willing to sacrifice almost anything to make it happen and thinks of little else than achieving his dream of a getting a steady job at a stable company and then getting married in order to reduce the burden on his ageing single mother.

Xu may think that a white-collar job is the only path to success but others do not quite see things the same way. Yuan Hanhan is introduced to us as a 17-year-old “high school drop out” but is in fact a talented artist and bona fide free spirit. After brief stint in a hippy cafe, she eventually achieves her dream of studying abroad at art school in Germany where she struggles to adapt to the relatively laidback quality of European society, affirming that in a developed nation like Germany no one sees the need to go on developing. She complains that Germans only need to do their routine jobs like little stones arranged in a line by the country – perhaps an ironic statement given the restrictive nature of Chinese society but also one with its own sense of logic which places the insistent work ethic clung to by Xu on parallel with an economic model which may already be out of date.

Xu gets his start as a telephonist making cold call insurance sales where the staff are drilled like a military cadre to regard their pencils as machine guns as their mics as grenades, their jobs not means of survival but an enterprise for the common good which drives tax receipts to benefit the entire nation. In a sense he has found his “way out” though his life will be one of soulless corporate drudgery, a fact brought home by his mother’s casual appraisal of his wedding album which features her son in a series of intensely romantic photographs in which he has “absolutely no expression”. Meanwhile, Hanhan remains a free spirit. Even if she never quite felt at home in Germany, she maintains a healthy interest in the wider world and is determined to forge her own path rather than become simply one of many identical “little stones”. For Baijuan, however, the future is much less rosy. Her grandfather, commiserating that perhaps she didn’t have the kind of aptitude for schooling that she might have liked, regards a woman’s education as unimportant, as Baijuan’s only “way out” is a “reliable” man whom they would like to find for her as soon as possible.

As Hanhan puts it in her philosophical closing speech, when it comes down to it birth is the most important factor of all. Simply by being born wealthy in Beijing she had advantages that others do not have. Baijuan’s fate is sealed in being born to a poor farming family in a remote rural region, while Xu constantly refers to his “family situation” as the reason he feels he has to become a success as soon as possible, hitting all the social landmarks at all the expected junctures. Each of our protagonists is looking for a “way out” of their unsatisfactory circumstances, and each of them finds it, but perhaps not quite in a way everyone would view as ”satisfactory”. Zheng’s vision of the new China is one in which the old ideology has failed, leaving behind it only an entrenched social hierarchy from which there may be no “way out” save a willing refusal to comply.

A Way Out was screened as part of the Chinese Visual Festival’s New Year programme at the BFI Southbank and is also available to rent online via Vimeo.

Trailer (English subtitles)

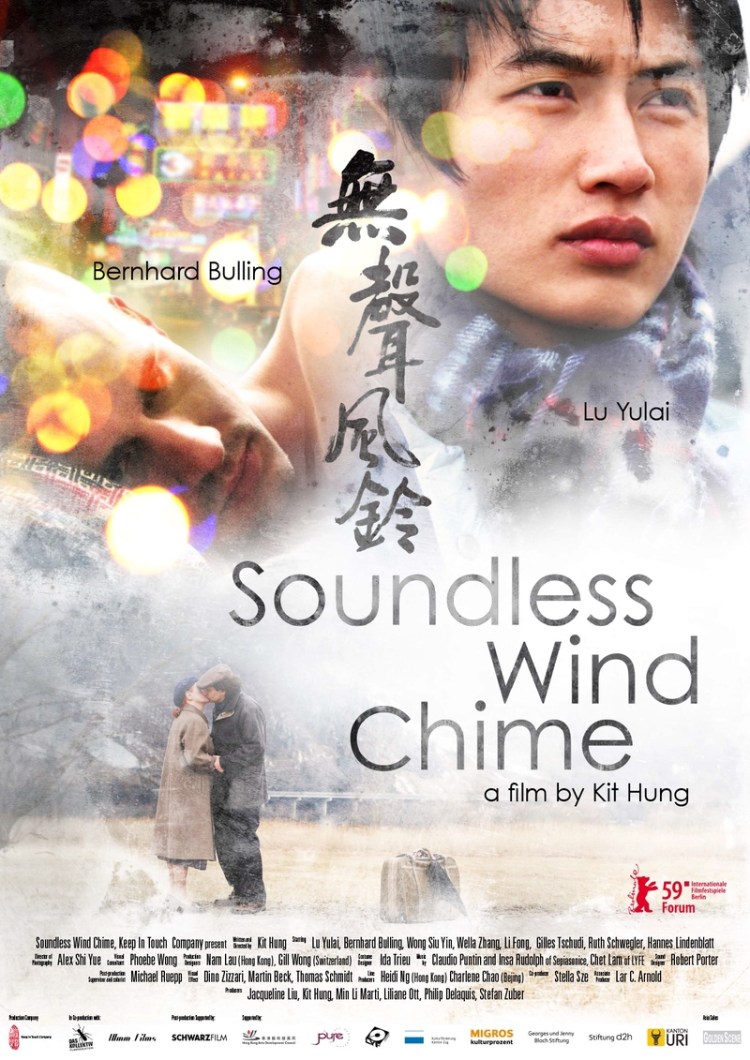

“Time, like a river, flows both day and night” as the narrator of Yang Chao’s poetical return to source Crosscurrent (長江圖, Chang Jiang Tu) tells us early on. Like the crosscurrent of the title, ship’s captain Chun sails forth yet also in retrograde as he chases a love he can never truly embrace. Truth be told, the philosophical poetry of a lonely sailor condemned to sail a predetermined course at the mercy of the winds and tides is often obscure and confused, like the half mad ramblings of one who’s spent too much time all alone at sea. Yet his melancholy passage is more metaphor than reality, or several interconnected metaphors as water yearns for shore but is pulled towards the ocean, a man yearns to free himself of his father’s spirit, and mankind yearns for the land yet disrupts and destroys it in its quest for mastery. Often frustrating in its obscurity, Crosscurrent’s breathtaking visuals are the key to unlocking its meditative sadness as they paint the beautiful landscape in its own conflicting colours.

“Time, like a river, flows both day and night” as the narrator of Yang Chao’s poetical return to source Crosscurrent (長江圖, Chang Jiang Tu) tells us early on. Like the crosscurrent of the title, ship’s captain Chun sails forth yet also in retrograde as he chases a love he can never truly embrace. Truth be told, the philosophical poetry of a lonely sailor condemned to sail a predetermined course at the mercy of the winds and tides is often obscure and confused, like the half mad ramblings of one who’s spent too much time all alone at sea. Yet his melancholy passage is more metaphor than reality, or several interconnected metaphors as water yearns for shore but is pulled towards the ocean, a man yearns to free himself of his father’s spirit, and mankind yearns for the land yet disrupts and destroys it in its quest for mastery. Often frustrating in its obscurity, Crosscurrent’s breathtaking visuals are the key to unlocking its meditative sadness as they paint the beautiful landscape in its own conflicting colours.