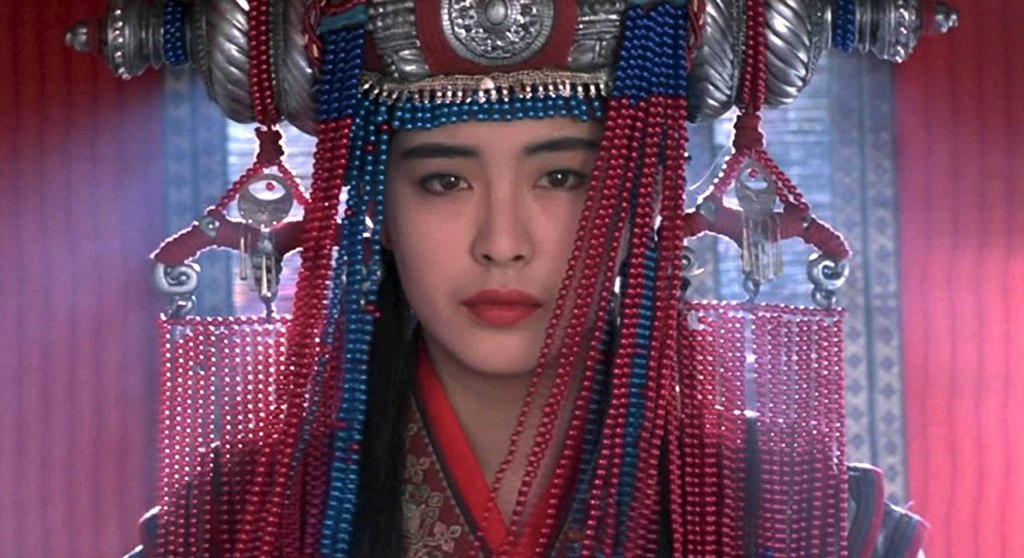

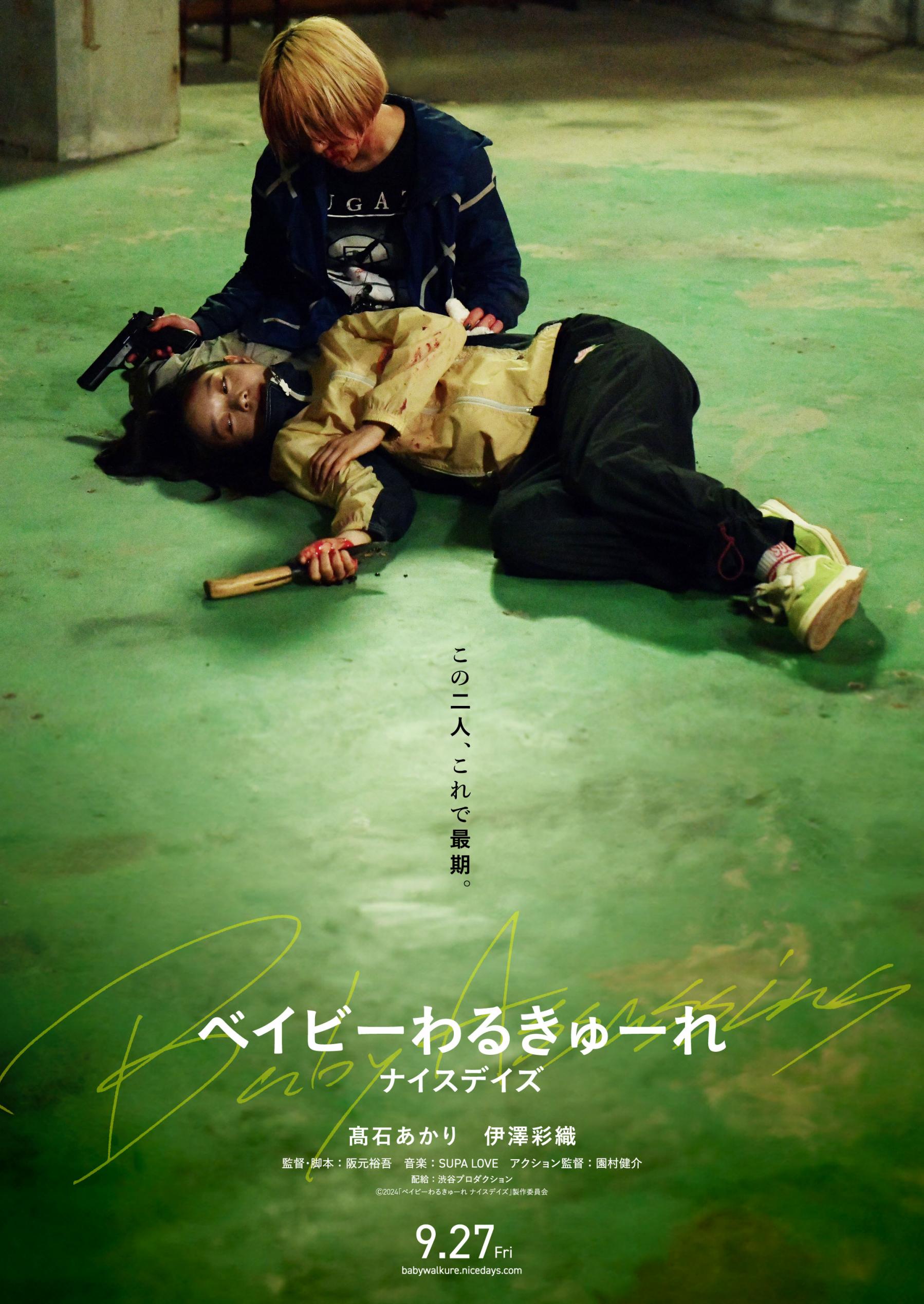

After beginning to conquer the demands of adulthood, Mahiro (Saori Izawa) and Chisato (Akari Takaishi) are taking a well-deserved break, or more like a working holiday to be precise, but soon find themselves with another unexpected mission to clean up a messy situation on behalf of the Guild. Baby Assassins: Nice Days (ベイビーわるきゅーれ ナイスデイズ, Baby Valkyrie: Nice Days), the third in series of deadpan slacker action movies from Yugo Sakamoto, adjusts the balance of the previous two films shifting more towards action than the girls’ aimless lives while setting them against an opponent who is anything but aimless.

In fact with the girls find their way to the home of Kaede Fuyumura (Sosuke Ikematsu), is plastered in ironic motivational slogans that seem to be a kind of parody of salaryman’s kaizen obsession. Fuyumura likes to rank things and wants to make sure he’s at the top, but also wants out of the game because he’s bored with it and also fed up with difficult clients frustrated when one takes ages to decide whether or not he should kill the target resulting unnecessary stress for them and an unsatisfying kill for Fuyumura. That’s largely why he’s agreed to this one last job of killing 150 people who took part in cancelling a university student online. The problem is that Fuyumura is a freelancer which presents a problem for the Guild which has decided he must die for violating their rules and bringing the profession into disrepute. Thus Mahiro and Chisato find themselves in an awkward position when they turn up to kill their latest target and realise they’ve been double booked to take out Fuyumura ’s kill.

The admin mixup, though it isn’t one really, rams home the series’ persistent absurdity that this weird world of assassins isn’t so different from contemporary corporate culture while the girls are still subject to the same problems as any other 20-something. This time around, we’re introduced to another prominent agency which is run out of a farmer’s agricultural co-op and hides weapons inside boxes of vegetables, while Mahiro and Chisato get a pair of supervisors with the de facto team leader Iruka (Atsuko Maeda) going off on lengthy rants about why it’s impossible to work with Gen Z while the girls struggle with her uptight dismissiveness. Yet even when there’s tension or discord, the fact remains that the Chisato and Mahiro are also part of a team and have a vast network of support to rely on including their cleanup squad while Fuyumura is a lone wolf who’s driven himself half out of his mind with his quest to be the best, a message is brought home to him when he approaches the farmer’s union to ask for “a replacement” after getting one of their guys killed only to be told off and reminded the farmers work as one big family rather than a series of disposable minions.

There is something a little poignant about Fuyumura’s wondering when his birthday is as if this small forgotten detail represented his missing humanity. The only time he feels like a human being is doing something mundane like cleaning his microwave and brushing his teeth. As she had the brothers in the previous film, Mahiro finds a kind connection with Fuyumura as they each discover a worthy match but knowing only one of them can survive. In an introspective movement, Mahiro asks Chisato if they can still hang out together on the other side if the worst happens, but she shuts the question down perhaps more in an attempt to shift Mahiro’s mindset but also berating herself for forgetting her birthday and making hurried plans to coverup her crime against friendship.

For all the absurdity about hitman union rules and rights of employment in an illegal profession, the films has a genuine affection for the relationship between the two girls as well as that between the wider team who are always around to have their back while they also take care to protect each other. Perhaps having to field a work crisis during their “holiday” is their final test of adulthood, and one they largely pass in enforcing their boundaries and defiantly having a good time anyway even if they did have to cancel their reservation at local barbecue restaurant to stakeout the home of a crazed killer. Once again featuring a series of well choreographed and innovative action sequences, the series’ third instalment seems to come into its own expanding the world of the Baby Assassins but setting them free inside it evidently a lot more at home with the concept of adulting.

Original trailer (no subtitles)