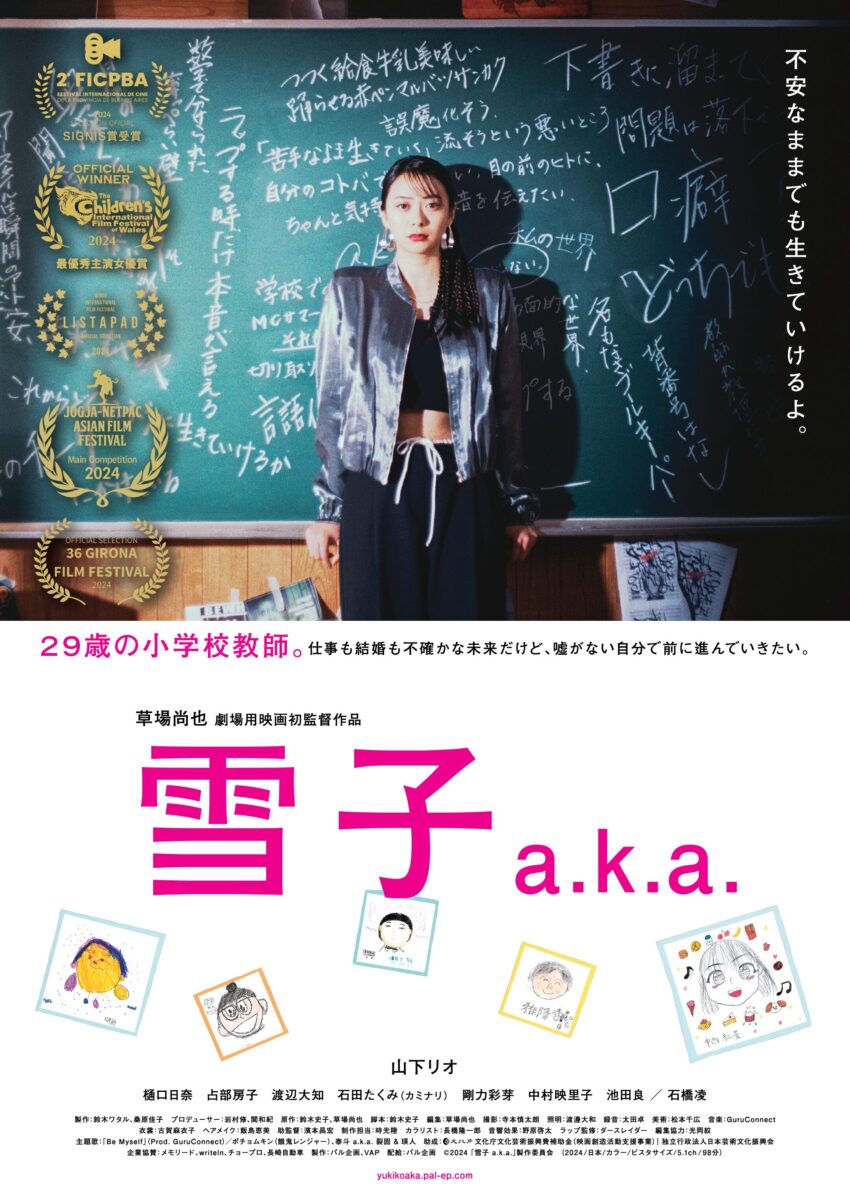

“Leave no one behind,” is the theory underpinning the SDGs that primary school teacher Yukiko (Rio Yamashita) is teaching to her students, but it’s also a practice that she unconsciously puts into practice only largely tends to forget to include herself. Timid and insecure, she makes little mark on the world around her and is afraid to express herself which she fears also interferes with her ability to interact with the children worrying that her reticence to speak up because she’s too worried they’ll say it’s all her fault prevents her from asking them if they’re alright or they need any help or guidance.

It’s only through the possibly surprising hobby of rap music that she finds an outlet where she can be herself and say everything that’s on her mind, only most of her raps are all about her anxiousness and inability to communicate. She has however found a supportive community in a local park where there are a group of rappers who seem to have her back and encourage her to get more into the hobby by participating in rap battles so she can express herself more. It seems though that part of her anxiety stems from a sense that she’s approaching a crossroads in life and is in many ways dissatisfied. She’s been in a long-term relationship with another teacher, Kodai (Daichi Watanabe), she met when they were both students but as he’s been assigned to another school a long way away, they only meet up at weekends.

All around her, her friends are getting married and it seems Kodai may also be ready to pop what seems to most an inevitable question, but there’s something that seems to be holding her back. Kodai later tells her that he doesn’t like the her that does rap, which suggests in a way that he doesn’t really want the version of her that can express herself or is confident in saying what she does and doesn’t want. He’s much more interested in the timid Yukiko who meekly goes along with what he wants and is too afraid to rock the boat. A fellow teacher, Riho (Hina Higuchi), has an ambition to be married with a child before 30, which is surprising to Yukiko and often criticised for being old fashioned. Yet what the film seems to insist is that neither perspective is wrong, merely different, and largely a matter of what suits each individual. Riho is cool in her own way for living her life the way she chooses even if it conflicts with the prevailing attitude of the contemporary society and it’s this sense of empowerment that Yukiko is really seeking as an older teacher, Ohsako (Fusako Urabe), explains. With her short hair and serious demeanour it might be assumed that the kids wouldn’t like Ohsako, but she’s actually their favourite and perhaps precisely because of her self-assuredness. In contrast to the ultramodern Riho she likes to hand write and draw her teaching materials as a means of transmitting sincerity and integrity to the children while acting as a voice of authority between the teachers.

Indeed, it’s Ohsako who largely teaches the film’s lessons and Yukiko how to embrace herself so that she can communicate better with the students explaining that her ability to pick up on the same anxieties in them is much more valuable than anything else. Locking eyes with a distressed young girl during a PE lesson, she quickly figures out that she’s experiencing menstrual cramps and is able to take her to the nurse’s office for some positive help and support. Meanwhile, she struggles with two boys in her class one of whom has become a school refuser and hikikomori. She visits Rui at his home every week with handouts but fails to make a breakthrough until she too is brave enough to expose her own fears and doubts. His deskmate Kotaro is now forced to join in with the girls either in front or behind when they’re asked to do pair work because of the painfully empty seat next to him.

But then unbeknownst to Yukiko, times have changed. Rui is not completely isolated but has been communicating with his friends, including Kotaro, through video games which as Kotaro’s father says is just as real to the children as talking in person. He’s also got really into educational apps and might have actually learned more by himself at home, which isn’t great for Yukiko’s self-esteem but at least he’s doing alright even if she might be becoming obsolete. Meanwhile the school still insists on making the kids read out loud to their parents who are then supposed to fill in a comment sheet but Kotaro writes those himself because his mum’s too busy. Nervously challenged by Yukiko, Kotaro’s mother asks what the educational point of the exercise is. She says she has her own way of communicating with her son and doesn’t have time for this meaningless bit of form filling. Yukiko’s insistence that it’s only 10 minutes belies a lack of understanding that Kotaro’s mother, who seems to be a working lone parent, simply doesn’t have another 10 minutes in her day. Still, the point is that Yukiko doesn’t really know the educational point of the exercise but has only been doing it because it’s what you do without giving it any real thought.

But as Ohsako had said, maybe neither way is wrong, it’s just a matter of personal taste. Through her rap music hobby, Yukiko begins to accept another side of herself while gaining the courage to be more confident and express herself more freely. She realises that it doesn’t really matter if she wins a rap battle or not because even putting herself out there was a minor victory that convinces her she has the power to do things with her life and live it in a way that best suits her while teaching similar lessons to the children and finally listening to her own advice.

Yukiko a.k.a screens in Chicago 22nd March as part of the 19th edition of Asian Pop-Up Cinema.

Trailer (English subtitles)

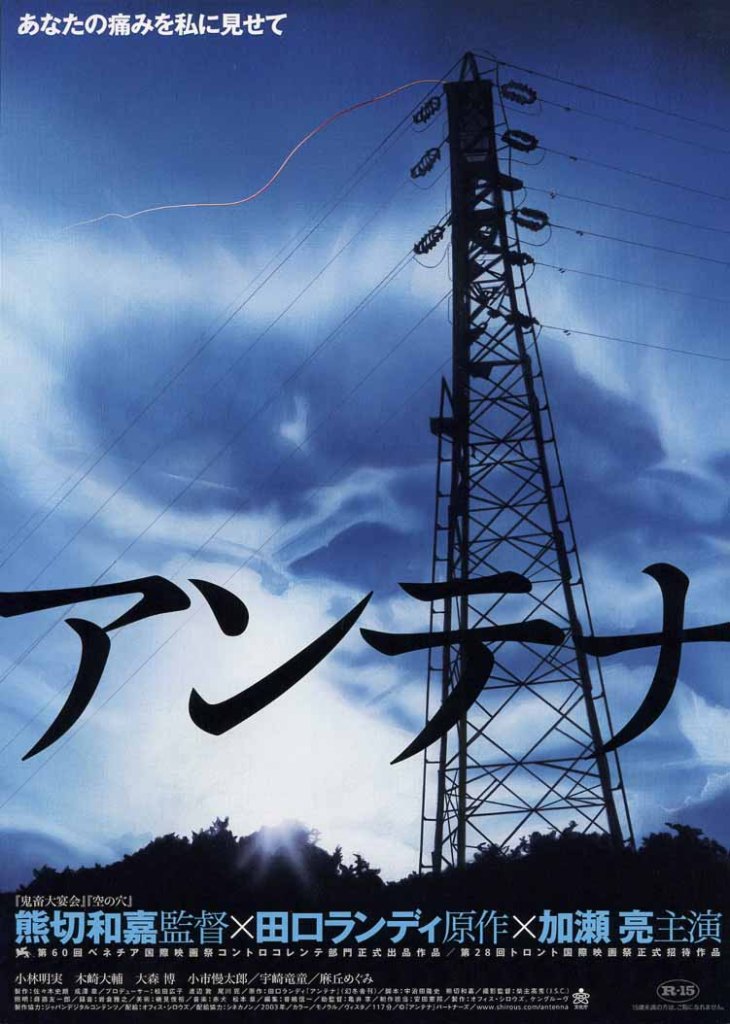

Scarring, both literal and mental, is at the heart of Kazuyoshi Kumakiri’s third feature, Antenna (アンテナ). Though it’s ironic that indentation should be the focus of a film whose title refers to a sensitive protuberance, Kumakiri’s adaptation of a novel by Randy Taguchi is indeed about feeling a way through. Anchored by a standout performance from Ryo Kase, Antenna is a surreal portrait of grief and repressed guilt as a family tragedy threatens to consume all of those left behind.

Scarring, both literal and mental, is at the heart of Kazuyoshi Kumakiri’s third feature, Antenna (アンテナ). Though it’s ironic that indentation should be the focus of a film whose title refers to a sensitive protuberance, Kumakiri’s adaptation of a novel by Randy Taguchi is indeed about feeling a way through. Anchored by a standout performance from Ryo Kase, Antenna is a surreal portrait of grief and repressed guilt as a family tragedy threatens to consume all of those left behind.