“You never know when it will end,” Aoi mutters to a concerned teacher. “The streaming period, and my life.” Asuna Yanagi’s Rainy Blue (レイニー ブルー) is a semi-autobiographical tale of a young woman figuring out how to live in the world while immersed in cinema. Her father may insist that she look at the reality, but Aoi’s world is already quite surreal even as she pours all her efforts into writing screenplays and watching films but otherwise floundering for direction.

To begin with, Aoi isn’t interested in cinema She just gets sent to see a film as punishment after getting caught setting off fireworks on the school roof because a local cinema has a special retrospective dedicated to actor Chishu Ryu who attended the same high school though probably 100 years previously. Despite scoffing at the idea and chuckling that everyone in the cinema is “old” while even the usher double checks to make sure she’s in the right place, Aoi is captivated by Ozu’s filmmaking and becomes a true convert to cinema to the extent that it completely takes over her life. She becomes the only member of the school’s film club, or as she’s find of reminding people “society”, and regularly turns up late after staying up all night watching movies.

To that extent, Aoi’s film obsession may not quite be healthy in that it leads her to make some questionable decisions with unintended consequences, such as getting arrested for “stalking” people after following them around as research for her screenplays. She also finds out that one of her old friends, who is also her father’s favourite example of a “good” daughter, is into compensated dating and in reality perhaps just as lost as she is. Aoi’s father no longer understands her and has become authoritarian and unforgiving. He regularly berates and shouts at her while making no real attempt at communication. He simply asks why she can’t be “normal” and concentrate on going to uni like the other girls while complaining about how “embarrassed” he would be if she doesn’t go because it would reflect badly on him as a parent.

Perhaps it’s not surprising that Aoi retreats into cinema to escape, but it’s also true that she finds a more supportive paternal presence in the guy at the cinema who turns out to have been a classmate of her mother’s. There’s a kind of poignancy in Aoi and her sister’s moment of confusion on realising that their mother was interested in films but they rarely watch them at home because her father doesn’t like them, while her mother rarely has time to go alone. Aoi’s love of cinemas as mediated by an old script she finds in the club room is also a way of connecting with her mother as a potentially more supportive parental figure in contrast to her father’s hardline authoritarianism.

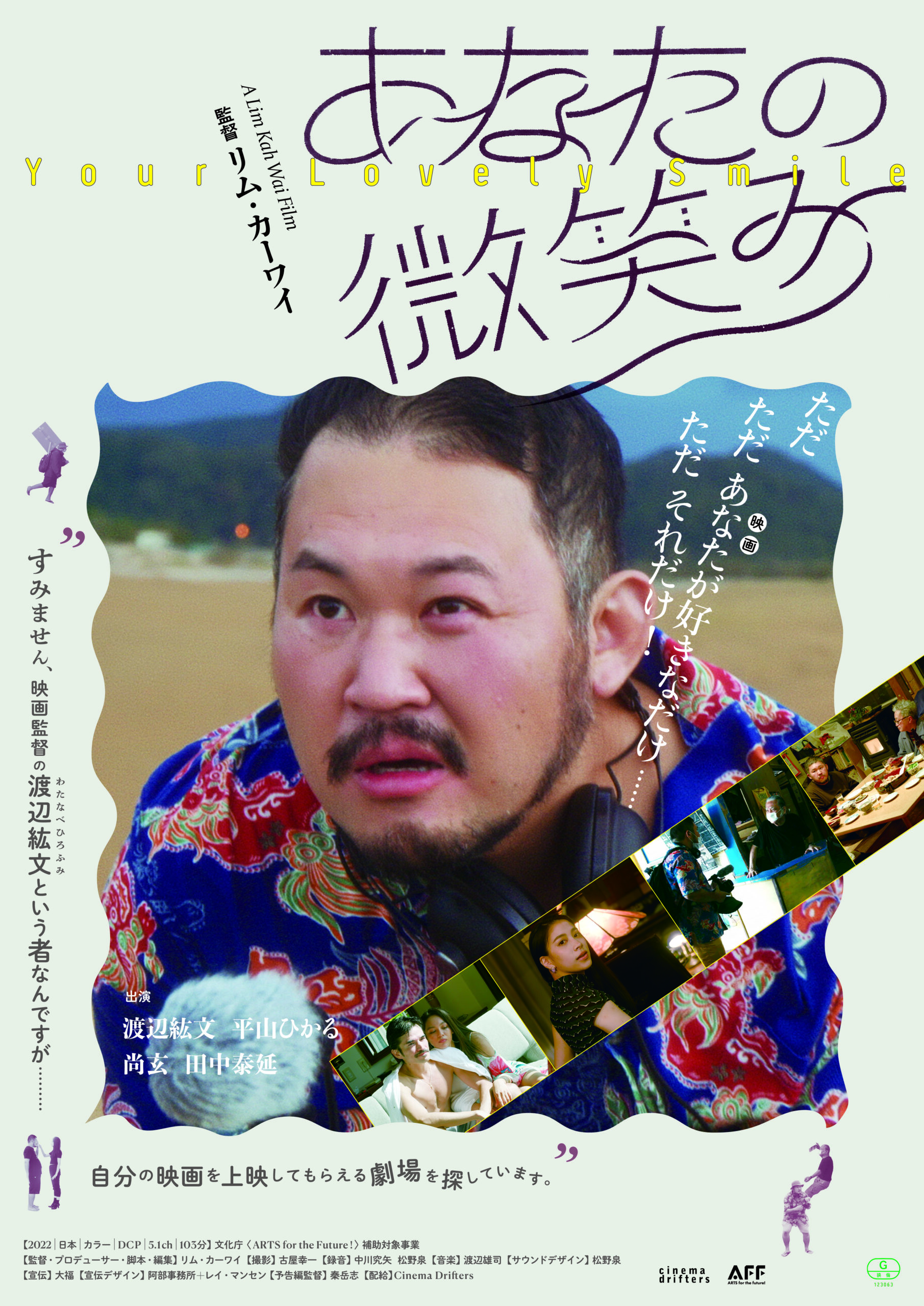

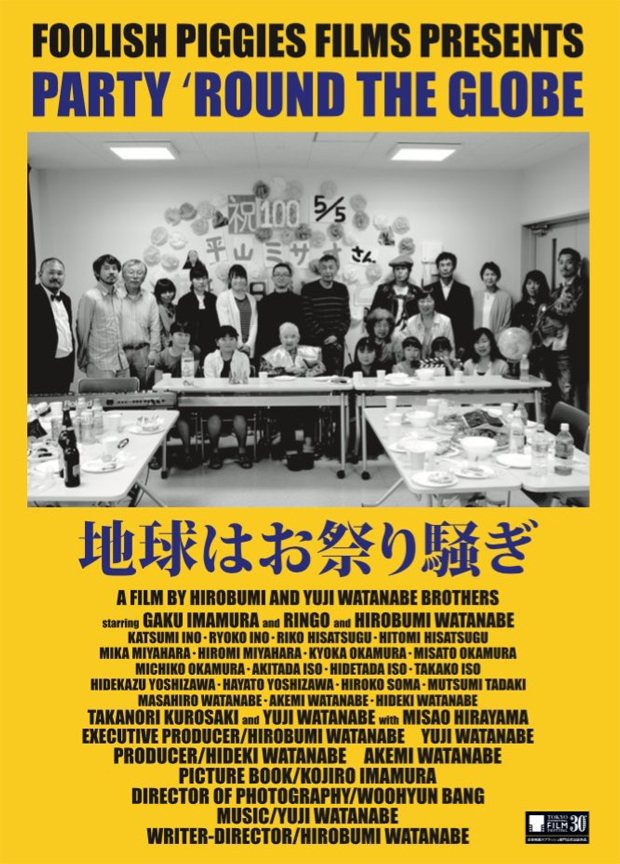

But then, in her love of cinema Aoi is absolutely certain and she’s no reason why she should hide it from anyone else. Her best friend at school is rather bafflingly played by 43-year-old film director Hirobume Watanabe who dresses in a pre-war school uniform complete with student’s cap and little round glasses that make him look strangely like a Studio Ghibli character. Usami is an otaku with a love of anime he thinks he’s kept hidden despite having several anime badges on his backpack and is too afraid to be out and proud about it because he knows he’ll be bullied, which he eventually is when Aoi enters a deeper moment of crisis and more or less abandons him and the school. Watanabe also appears as a weirdly inspirational film director who has a go at an audience member at a q&a who asks him why his film is so nihilistic only for him to turn the question back on her and angrily insist that film can illuminate the way forward for those like Aoi who feel themselves to be lost.

Thanks to all these strange adventures, her various friendships, and even her father’s animosity, Aoi eventually figures out what she wants to do with her life and gains the courage to go after it no matter what anyone else might say. Set in the picturesque environment of rural Kumamoto, the film’s gentle, laid-back aesthetic belies the storm at its centre and the rainy blue that surrounds the heroine until she too finally finds her way through the labyrinths of cinema.

Rainy Blue (レイニー ブルー, Asuna Yanagi, 2025) screened as part of this year’s Osaka Asian Film Festival.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

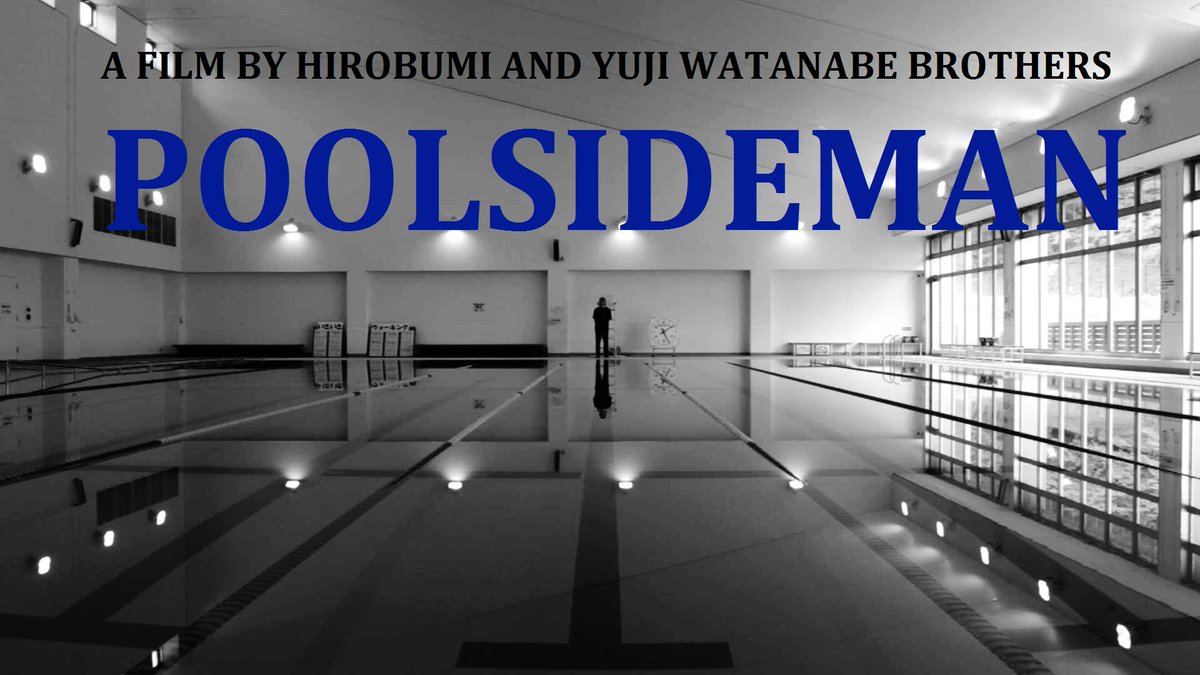

Around halfway through Poolsideman (プールサイドマン), the director himself playing an overly chatty colleague of the film’s protagonist, embarks on a lengthy rant about encroaching middle-age which is instantly relatable to those who find themselves at a similar juncture. He’s sure the world seemed better when he was a child, there wasn’t all of this distress and anxiety – everything just seemed like it would go on forever but time has inexplicably sped up with a series of rapid changes packed into recent years. The life of a poolsideman is improbably intense, or at least it is for Mizuhara (Gaku Imamura) whose days are all the same but filled with tension and the low simmer of something waiting to explode. Loosely inspired by the real life case of a man who left Japan for the Middle East with the idea of joining Isis, Poolsideman wants to explore why such a surreal thing might happen but finds it all too plausible.

Around halfway through Poolsideman (プールサイドマン), the director himself playing an overly chatty colleague of the film’s protagonist, embarks on a lengthy rant about encroaching middle-age which is instantly relatable to those who find themselves at a similar juncture. He’s sure the world seemed better when he was a child, there wasn’t all of this distress and anxiety – everything just seemed like it would go on forever but time has inexplicably sped up with a series of rapid changes packed into recent years. The life of a poolsideman is improbably intense, or at least it is for Mizuhara (Gaku Imamura) whose days are all the same but filled with tension and the low simmer of something waiting to explode. Loosely inspired by the real life case of a man who left Japan for the Middle East with the idea of joining Isis, Poolsideman wants to explore why such a surreal thing might happen but finds it all too plausible.