For some, life is a series of stages. Education, work, marriage, parenthood, death. For others, life is more like a continuous stream, a series of minor movements in an ongoing symphony. The couple at the centre of Kim Dae-hwan’s second film, The First Lap (초행, Cho-haeng), are contentedly (for the most part) trapped in a permanent adolescence living chaotic lives aside from what most would consider the mainstream. Together for seven years but still unmarried, Ji-young (Kim Saebyuk) and Su-hyeon (Cho Hyun-chul) are forced to confront their liminal status when the twin pressures of a pregnancy scare and obligatory family visits place a strain on their otherwise settled relationship.

For some, life is a series of stages. Education, work, marriage, parenthood, death. For others, life is more like a continuous stream, a series of minor movements in an ongoing symphony. The couple at the centre of Kim Dae-hwan’s second film, The First Lap (초행, Cho-haeng), are contentedly (for the most part) trapped in a permanent adolescence living chaotic lives aside from what most would consider the mainstream. Together for seven years but still unmarried, Ji-young (Kim Saebyuk) and Su-hyeon (Cho Hyun-chul) are forced to confront their liminal status when the twin pressures of a pregnancy scare and obligatory family visits place a strain on their otherwise settled relationship.

Their two year rental contract up for renewal, Ji-young and Su-hyeon are packing up to move somewhere cheaper when Su-hyeon gets an awkward phone call from his brother inviting him home for his father’s 60th birthday party. Su-hyeon obviously does not want to go and makes a series of excuses despite Ji-young’s urging that he should probably attend. Ji-young also drops the bombshell that she’s worried she might be pregnant which raises several problems for the couple both financial and emotional. The next day they set off on a trip, but it’s to visit Ji-young’s well-to-do parents in their new high-rise Incheon apartment.

Kim structures the film around the two very distinct family environments, subtly suggesting the various reasons neither Ji-young or Su-hyeon are in favour of moving onto the next stage stems back to their own problematic upbringings. Though Ji-young’s family are financially secure and occupy a traditionally middle-class social stratum with her father working for the government and mother in real estate, the home is a cold one and Ji-young’s mother a harsh and direct woman who is unafraid to speak her mind regarding what she sees as her daughter’s poor life choices. In what will become a recurrent motif, Ji-young’s mother wants to know why the couple aren’t married, pointing out Ji-young’s advancing age and the unseemliness of an unmarried woman over thirty. After pointedly telling Ji-young she is not proud of her and in fact thinks of her as a disappointing embarrassment, Ji-young’s mother goes off the deep end on discovering the pregnancy test in Ji-young’s bag, driven into a fury of conservative discombobulation at the thought of being grandmother to a child born out of wedlock.

Ji-young is afraid to become a mother in case she becomes hers and does to her child what her mother has done to her. Su-hyeon has a similar problem, though his is one of intense discomfort with his familial environment in growing up in an unhappy home. Travelling back to the tiny fishing village where Su-hyeon’s parents used to own a sashimi restaurant but now apparently work for a factory which has all but destroyed the area’s previously lucrative tourist industry, Ji-young could not be more out of place. Unlike the ordered coldness of Ji-young’s parents’ swanky apartment, Su-hyeon’s family home is one of repressed heat in which longstanding arguments seem permanently primed to spark. Su-hyeon, depressingly used to this kind of scene, ushers Ji-young out the door just as it looks about to kick off, only for her to urge him back to “do something’ – something he’s long given up the idea of doing. Su-hyeon does not want to live in this kind of family or make his wife as miserable as his mother has been married to a man she can’t stand who holds only contempt for his more sensitive son.

Thus Ji-young and Su-hyeon find themselves at an impasse facing both economic anxiety and long-standing emotional fears for the future. All around them, society seems to be in flux, Su-hyeon travels through a subway as protestors from the “Candlelight Revolution” make their way home after another long day spent peacefully protesting the administration of Park Geun-hye. Even young couples like Ji-young and Su-hyeon not usually interested in politics are drawn to the movement, suddenly finding themselves free to consider a better future, not the one they’re supposed to have but the one they actually want (if they can figure out what that actually is). A visit to the protest proves a surprisingly romantic outing. Sharing hot soup in the midst of candle light and gentle music, the pair wander around, still directionless and unsure where exactly it is that they’re going but happy to be together wherever it is they might end up.

Screened at London Korean Film Festival 2017. Screening again in Manchester in 11th November, 1.30pm.

Original trailer (English subtitles)

When tragedy strikes the one thing you ought to be able to rely on is your family, but when the tragedy occurs within that sacred space which exits between you what is to be done? Yosuke Takeuchi’s The Sower (種をまく人, Tane wo Maku Hito) attempts to provide an answer whilst putting one very ordinary, loving and forgiving family through a series of tests and tragedies. Lies, regret, and despair conspire to ruin the lives of four once happy people but even in the midst of such a shocking, unexpected event there is still time to turn towards the sun rather than continuing in the darkness.

When tragedy strikes the one thing you ought to be able to rely on is your family, but when the tragedy occurs within that sacred space which exits between you what is to be done? Yosuke Takeuchi’s The Sower (種をまく人, Tane wo Maku Hito) attempts to provide an answer whilst putting one very ordinary, loving and forgiving family through a series of tests and tragedies. Lies, regret, and despair conspire to ruin the lives of four once happy people but even in the midst of such a shocking, unexpected event there is still time to turn towards the sun rather than continuing in the darkness. Yukihiko Tsutsumi has made some of the most popular films at the Japanese box office yet his name might not be one that’s instantly familiar to filmgoers. Tsutsumi has become a top level creator of mainstream blockbusters, often inspired by established franchises such as TV drama or manga. Skilled in many genres from the epic sci-fi of Twentieth Century Boys to the mysterious comedy of Trick and the action of SPEC, Tsutsumi’s consumate abilities have taken on an anonymous quality as the franchise takes centre stage which makes this indie leaning black and white exploration of the lives of a group of homeless people in Nagoya all the more surprising.

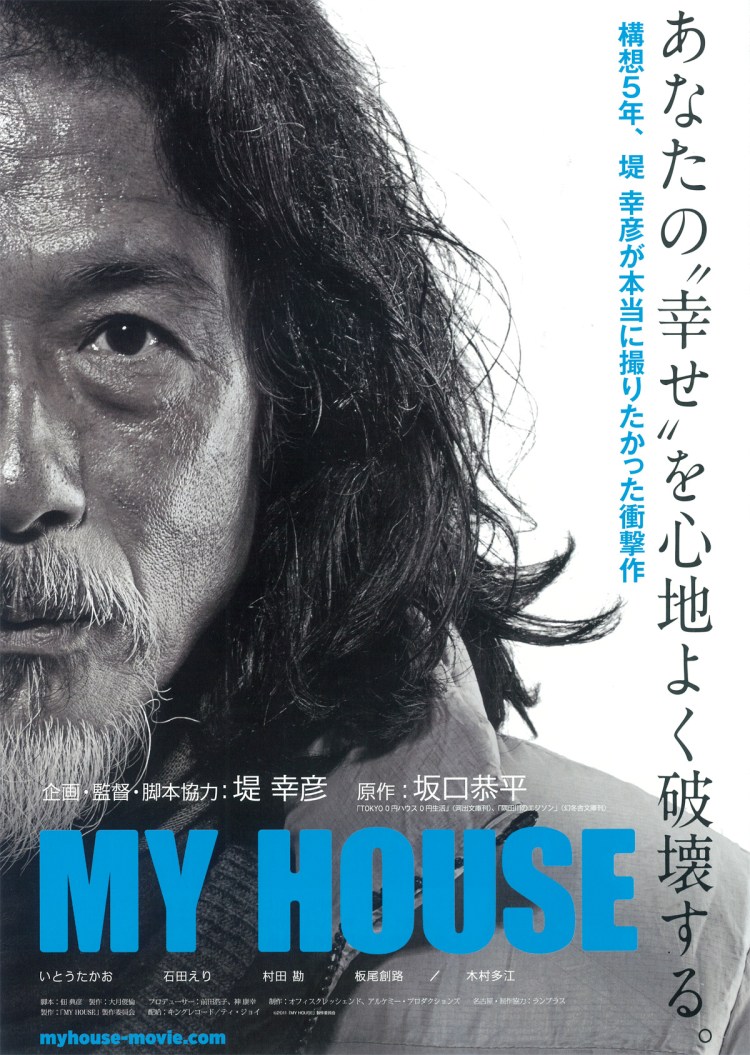

Yukihiko Tsutsumi has made some of the most popular films at the Japanese box office yet his name might not be one that’s instantly familiar to filmgoers. Tsutsumi has become a top level creator of mainstream blockbusters, often inspired by established franchises such as TV drama or manga. Skilled in many genres from the epic sci-fi of Twentieth Century Boys to the mysterious comedy of Trick and the action of SPEC, Tsutsumi’s consumate abilities have taken on an anonymous quality as the franchise takes centre stage which makes this indie leaning black and white exploration of the lives of a group of homeless people in Nagoya all the more surprising. Review of Zhang Lu’s A Quiet Dream (춘몽, Chun-mong) first published by

Review of Zhang Lu’s A Quiet Dream (춘몽, Chun-mong) first published by