Artistic polymath Shuji Terayama was fond of claiming that more could be learned about life from boxing rings and race courses than from conventional study. Immersing himself in the countercultural epicentre of mid-century Shinjuku, he became known for iconoclastic street theatre before shifting to film, instantly recognisable for his striking use of colour filter and theatrical, avant-garde aesthetic. 1977’s Boxer (ボクサー) is, however, his most conventional experiment, a generic tale of a struggling boxer yearning to be a champion and battling himself, along with his society, in the claustrophobic arena of the ring, but for all the expected triumph it’s futility which marks his life and the ropes which restrain rather than liberate.

Artistic polymath Shuji Terayama was fond of claiming that more could be learned about life from boxing rings and race courses than from conventional study. Immersing himself in the countercultural epicentre of mid-century Shinjuku, he became known for iconoclastic street theatre before shifting to film, instantly recognisable for his striking use of colour filter and theatrical, avant-garde aesthetic. 1977’s Boxer (ボクサー) is, however, his most conventional experiment, a generic tale of a struggling boxer yearning to be a champion and battling himself, along with his society, in the claustrophobic arena of the ring, but for all the expected triumph it’s futility which marks his life and the ropes which restrain rather than liberate.

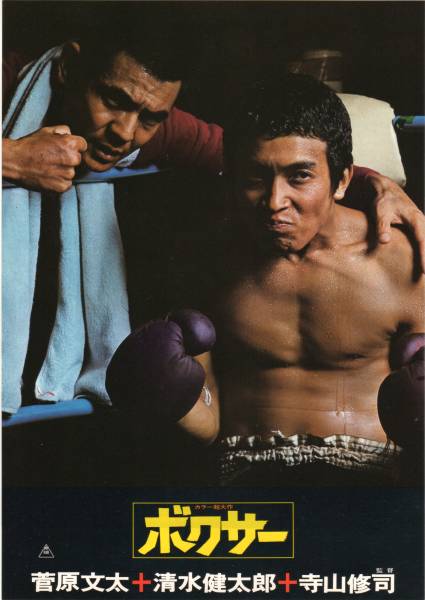

Former boxing champion Hayato (Bunta Sugawara) now lives a lonely existence alone with his beloved dog in a rundown boarding house. His brother is about to be married and wanted him to be in the engagement photos, but he told the young couple to go ahead without him. He may come to regret that because his brother quickly becomes the victim of an accident that may not have been quite that at the construction site where he and his fiancée worked. It seems that another employee, Tenma (Kentaro Shimizu) – an aspiring boxer with a limp, had taken a liking to the same girl and, either distracted by the news she intended to marry someone else, or not thinking clearly, he allowed his digger to hit Hayato’s brother and kill him. Of course, Hayato is not happy about that and determines to track Tenma down, looking for him at a neighbourhood bar where a small boy guides him to the gym, which he is eventually expelled from by the other boxers. Nevertheless, Tenma, having heard about Hayato’s past and been dismissed by his trainers because of his disability, is determined to overcome the debt that exists between them and become Hayato’s mentee hoping to go on to boxing glory.

Like many a Shinjuku tale, this is one of scrappy chancers longing to escape the vice-like grip of an underworld that refuses to release them. In the land of broken dreams, the hopeless man is king, and Hayato is nothing if not hopeless. Years ago, we’re told, he was a champion, yet he suddenly quit boxing mid-way through a bout that he was clearly winning. He had a wife and daughter, but now lives alone (except for the dog), making a living by pasting up flyers. In response to Tenma’s request, Hayato recounts to him the histories of boxing champions in Japan all of whom met a sticky end: dying of typhus in Manchuria, drowning after demobilisation, dying under a bridge, hit by a train, suicide after revenge on a yakuza who’d killed his brother, killed when a runaway truck hit his home, car accidents etc. The boxing match which opens the film is preceded by a minute of silence for a champion who died just a few days previously. So what, Hayato seems to say, we fight but we all die in the ring anyway. What’s the point?

Still, for all the meaningless of his success, he too finds a kind of purpose in Tenma’s quest even if he knows it’s futile and that it is perhaps perverse to commit to saving the man who killed his brother either by accident, as he claims, or out of romantic jealousy. Tenma tells him that he wants to be a champion to appear on TV and be famous. He has, it seems, something to prove. Hayato tells him that boxing’s not for everyone, cruelly echoing the words of the president of the boxing society in his letter explaining to Tenma that there is no place for him in the boxing world because of his disability. His reasoning is however different. He asks him if he is able to hate, to which which he replies that yes, he hates his mother, father, brother, and in fact “the whole damn world” which makes him a perfect mirror for his defeated mentor.

Terayama opens the film with a melancholy black and white sequence in which a boxer walks down a long corridor towards a door filled with light while other contenders pass him from the opposite direction, some badly beaten and others unable to walk. This is the price, he seems to say, a literal manifestation of life’s battery. Even the denizens of the strangely colourful, warm and cheerful little neighbourhood bar with its Taisho intellectual, former actress turned streetwalker, smoking child, and bookmakers who don’t pay their bills, are fighting a heavy battle, crushed under the weight of their broken dreams. Hayato tries to offer encouragement from the sidelines, “Get up if you refuse to be a loser”, he yells to a barely conscious Tenma struggling raise himself from the mat, but even if he does what will he gain? Suitcase in hand the women leave looking for better lives, while Tenma struggles to escape from the ring, chasing hollow victories of illusionary manhood but finding salvation only in the struggle.

Opening sequence (no subtitles)

Caught in a moment of transition in more ways than one, Throw Away Your Books, Rally in the Streets (書を捨てよ町へ出よう, Sho o Suteyo Machi e Deyo) is a clarion call to apathetic youth in the dying days of ‘60s youthful rebellion. Neatly bridging the gap between post-war avant-garde and the punk cinema of the ‘70s and ‘80s, Terayama experiments gleefully with a psychedelic, surreal rock musical which is first and foremost a sensory rather than a cerebral experience.

Caught in a moment of transition in more ways than one, Throw Away Your Books, Rally in the Streets (書を捨てよ町へ出よう, Sho o Suteyo Machi e Deyo) is a clarion call to apathetic youth in the dying days of ‘60s youthful rebellion. Neatly bridging the gap between post-war avant-garde and the punk cinema of the ‘70s and ‘80s, Terayama experiments gleefully with a psychedelic, surreal rock musical which is first and foremost a sensory rather than a cerebral experience.