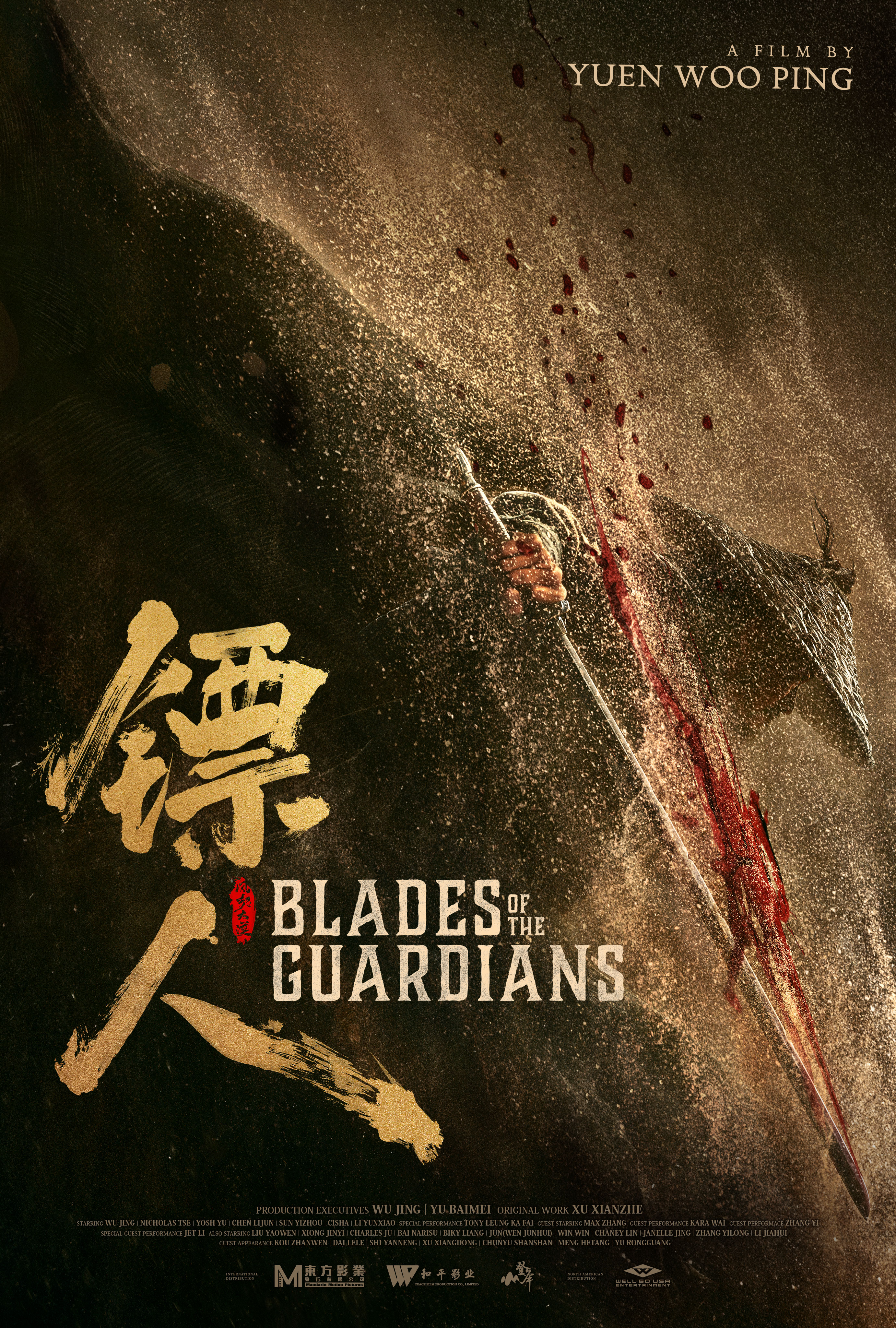

“I haven’t seen moves like that in the martial world in forty years,” quips a bystander in a post-credits sequence, and this adaptation of the manhua by the legendary Yuen Woo-Ping certainly does its best to bring back some of the charm of classic wuxia. Produced by star Wu Jing, Blades of the Guardians (镖人:风起大漠, biāo rén fēng qǐ dàmò) also features a cameo appearance by Jet Li as well Nicholas Tse, Tony Leung Ka-fai, and Kara Wai, as a cynical bounty hunter rediscovers his duty towards the common people while escorting a would be revolutionary to the ancient capital of Chang’an.

A former soldier, Dao Ma (Wu Jing) now wanders the land with a child in tow in search of wanted criminals, but when he finds them, makes an offer instead. Pay him triple the bounty, and he’ll forget he ever saw them. As we’re told, this is a world of constant corruption under the oppressive rule of the Sui dynasty. Zhi Shilang (Sun Yizhou) is the famed leader of the Flower Rebellion that hopes to clear the air, which makes him the number one fugitive of the current moment. This is slightly annoying to Dao Ma in that it necessarily means he’s number two when forced on the run after killing a corrupt local governor (Jet Li) in defence of an innkeeper with a hidden martial arts background whose family the official was going to seize for the non-payment of taxes. Taking refuge in the small township of Mojia, Dao Ma is given a mission by the sympathetic Chief Mo (Tony Leung Ka-fai) who agrees to cancel all his debts if he escorts Zhi Shilang to Chang’an safely before they’re both killed by hoards of marauding bounty hunters, regular bandits, government troops including two of Dao Ma’s old friends, or the former fiancée of ally Ayuya (Chen Lijun), the self-proclaimed Khan, He Yixuan (Ci Sha).

When given the mission, Dao Ma asked why he should care about the common people or Zhi Shilang’s revolution only to be swept along as they make their way towards the capital and witness both the esteem with which Zhi Shilang seems to be held by those who believe in his cause and the venality of the bounty hunters along with the mindless cruelty of He Yexian’s minions. As is usual in these kinds of stories, Mojia is a idyllic haven of cherry trees in bloom where the people dance and sing and are kind to each other, which is to say, the seat of the real China. Though Ayuya longs to see Chang’an and harbours mild resentment towards her father for his “control” over her, Chief Mo is the moral centre of the film and not least because he cares for nothing more than his daughter’s happiness. When she decides not to marry He Yixian on account of his bloodthirsty lust for power, Mo walks barefoot through the scorched land of the desert to free her from the obligation and, after all, has trained her to become a fearsome archer rather than just someone’s wife or a pawn to be played as he sees fit.

But as someone else says, who is not a pawn in this world? There are other shadow forces lurking behind the scenes playing a game of their own while taking advantage of the corrupt chaos of the Sui Dynasty court. Dao Ma, however, revels in his outsider status. “Not even the gods control me now,” he jokes in advocating for his freelance lifestyle loafing around as a cynical bounty hunter who can choose when to work and where to go, in contrast to his life as a soldier of the Sui forced to carry out their inhuman demands. When the innkeeper’s son tells him he wants to be a swordsman too, Dao Ma gives him a sword as a symbol of freedom and instructs him to take a horse and go wherever he wants when he’s old enough. His fate is his own, whatever his father might have said.

If that might sound like a surprising and somewhat subversive advocation for individualism, the final message is one of solidarity, as Dao Ma rediscovers his duty to the people and various others also fall in behind Zhi Shilang, who is hilariously inept at things like riding a horse and remaining calm under fire, to take the revolution all the way to Chang’an. With stunning action sequences including an epic sandstorm battle, the film successfully marries old-school wuxia charm with a contemporary sensibility and an unexpectedly revolutionary spirit as Dao Ma and friends ride off to tackle corruption at the heart of government.

Blades of the Guardians is in US cinemas now courtesy of Well Go USA.

Trailer (English subtitles)

Often, people will try to convince of the merits of something or other by considerably over compensating for its faults. Therefore when you see a movie marketed as the X-ian version of X, starring just about everyone and with a budget bigger than the GDP of a small nation you should learn to be wary rather than impressed. If you’ve followed this very sage advice, you will fare better than this reviewer and not find yourself parked in front of a cinema screen for two hours of non-sensical European fantasy influenced epic adventure such as is League of Gods (3D封神榜, 3D Fēng Shén Bǎng).

Often, people will try to convince of the merits of something or other by considerably over compensating for its faults. Therefore when you see a movie marketed as the X-ian version of X, starring just about everyone and with a budget bigger than the GDP of a small nation you should learn to be wary rather than impressed. If you’ve followed this very sage advice, you will fare better than this reviewer and not find yourself parked in front of a cinema screen for two hours of non-sensical European fantasy influenced epic adventure such as is League of Gods (3D封神榜, 3D Fēng Shén Bǎng).