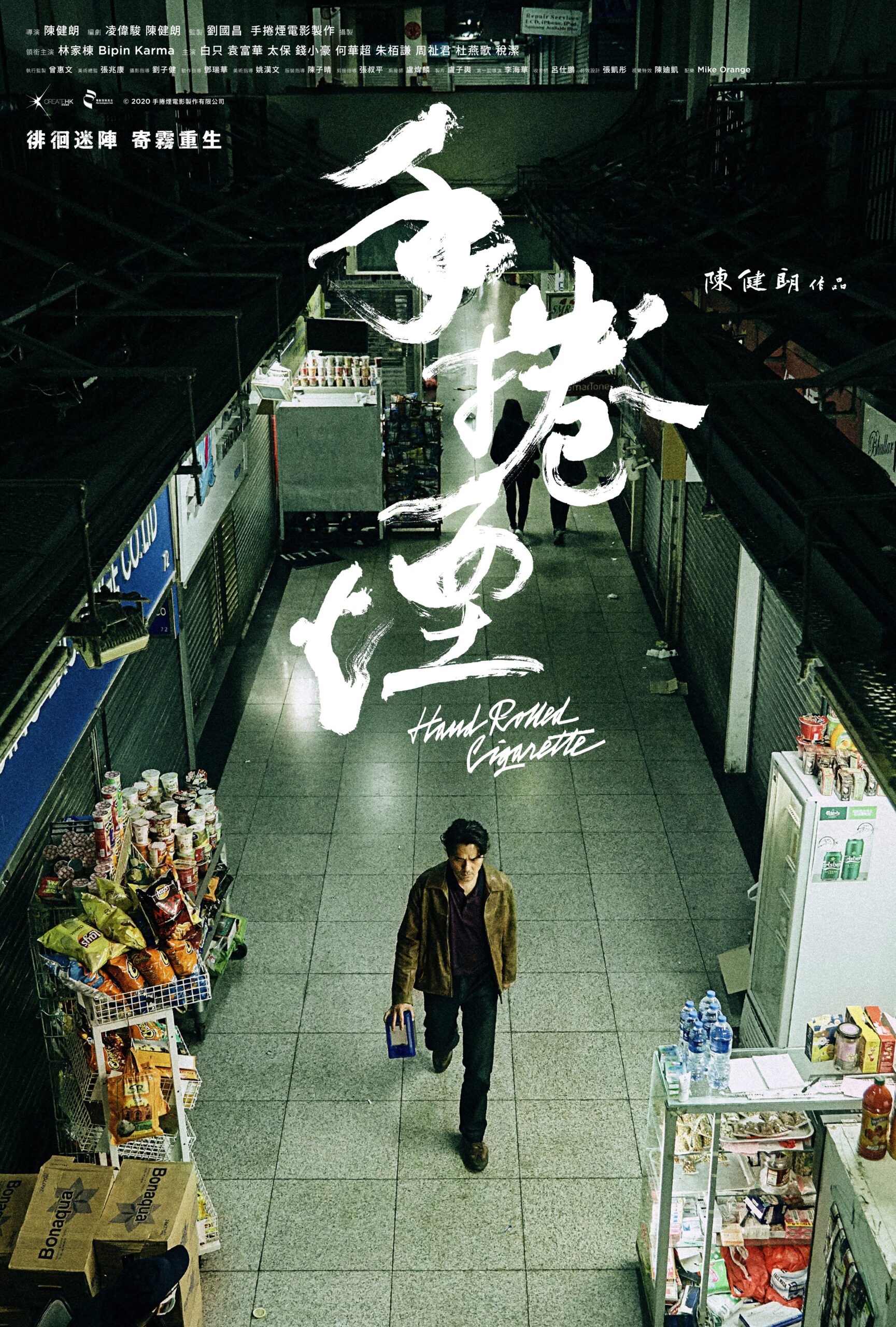

A former serviceman turned triad middleman bonds with a similarly oppressed South Asian petty criminal in Chan Kin-long’s noirish crime drama Hand Rolled Cigarette (手捲煙). An unexpected awards contender, the first directorial effort from actor Chan aligns its disparate heroes as two men in a sense betrayed by the world in which they live, one longing for a way out and the other too convinced he no longer deserves one to continue looking.

“Let’s start over” Chiu (Gordon Lam Ka-tung) philosophically muses over a cigarette contemplating the coming handover. As a brief title card explains, when the British Army pulled out of Hong Kong, it hung its local recruits out to dry, disbanding their units and leaving them entirely without support. 25 years later, Chiu has become a dejected triad middleman, as we first meet him setting up a dubious deal for smuggled turtles between Taiwanese mobster Pickle (To Yin-gor) and local top dog Boss Tai (Ben Yuen). On his way back to his flat in Chungking Mansions, Chiu literally runs into a South Asian man apparently in the middle of a drug deal. Kapil (Bitto Singh Hartihan) dreams of bigger prizes, listening to the stock market report on the morning news and musing about robbing a bank. His cousin Mani (Bipin Karma), more conflicted in their criminal activities, cautions him against it reminding him that they already face discrimination and don’t need to add to their precarious position by giving their ethnicity a bad name. “If we have money people can’t look down on us” Kapil counters, seemingly desperate to escape his difficult circumstances by any means possible which eventually leads him to make the incredibly bad decision to cheat local triads out of their drug supply. Leaving Mani and his schoolboy brother Mansu (Anees) alone to carry the can (literally), Kapil takes off while Mani finds himself crawling into Chiu’s flat for refuge when chased by Boss Tai’s chief goon Chook (Michael Ning). Unwilling at first, Chiu agrees to let Mani stay, for a price, only to find himself falling ever deeper into a grim nexus of underworld drama.

Chiu’s plight as a former British serviceman makes him in a sense an exile in his own land, a displaced soul free floating without clear direction unable to move on from the colonial past. We later learn that he is in a sense attempting to atone for a karmic debt relating to the death of a friend during the Asian financial crisis, also beginning in 1997, of which he was a double victim. Most of his old army buddies have moved on and found new ways of living, some of them rejecting him for his role in their friend’s death and tendency to get himself into trouble while Chiu can only descend further into nihilistic self-loathing in his self-destructive triad-adjacent lifestyle.

Mani, by contrast, did not approve of his cousin’s criminality, particularly resenting him for using Mansu’s schoolbag as a means of shifting drugs. He dreams of a better life but sees few other options for himself, hoping at least to send Mansu to university and ensure he doesn’t share the same fate. Chiu continues to refer to him solely by a racial slur, but simultaneously intervenes in the marketplace when Chook and his guys hassle another South Asian guy insisting that they’re all locals and therefore all his “homies”, despite himself warming to the young man and even going so far as to sort out child care for Mansu otherwise left on his own. “Harmony brings wealth” Boss Tai ironically exclaims, but harmony is it seems hard to come by, Chiu’s sometime Mainland girlfriend expressing a desire to return because the city is not as she assumed it would be while little Mansu is constantly getting in fights because the other kids won’t play with him.

“There’s always a way out. I’ll start over” Chiu again tells Mani, though he seems unconvinced. Clearing his debts karmic and otherwise, Chiu discovers only more emptiness and futility while perhaps redeeming himself in rebelling against the world of infinite corruption that proved so difficult to escape. A moody social drama with noir flourishes, Chan’s fatalistic crime story is one of national betrayals culminating in a highly stylised, unusually brutal action finale partially set in the green-tinted hellscape of a gangster’s illegal operating theatre. Men like Chiu, it seems, may not be able to survive in the new Hong Kong but then perhaps few can.

Hand Rolled Cigarette streams in Europe until 2nd July as part of this year’s hybrid edition Udine Far East Film Festival.

Original trailer (English / Traditional Chinese subtitles)