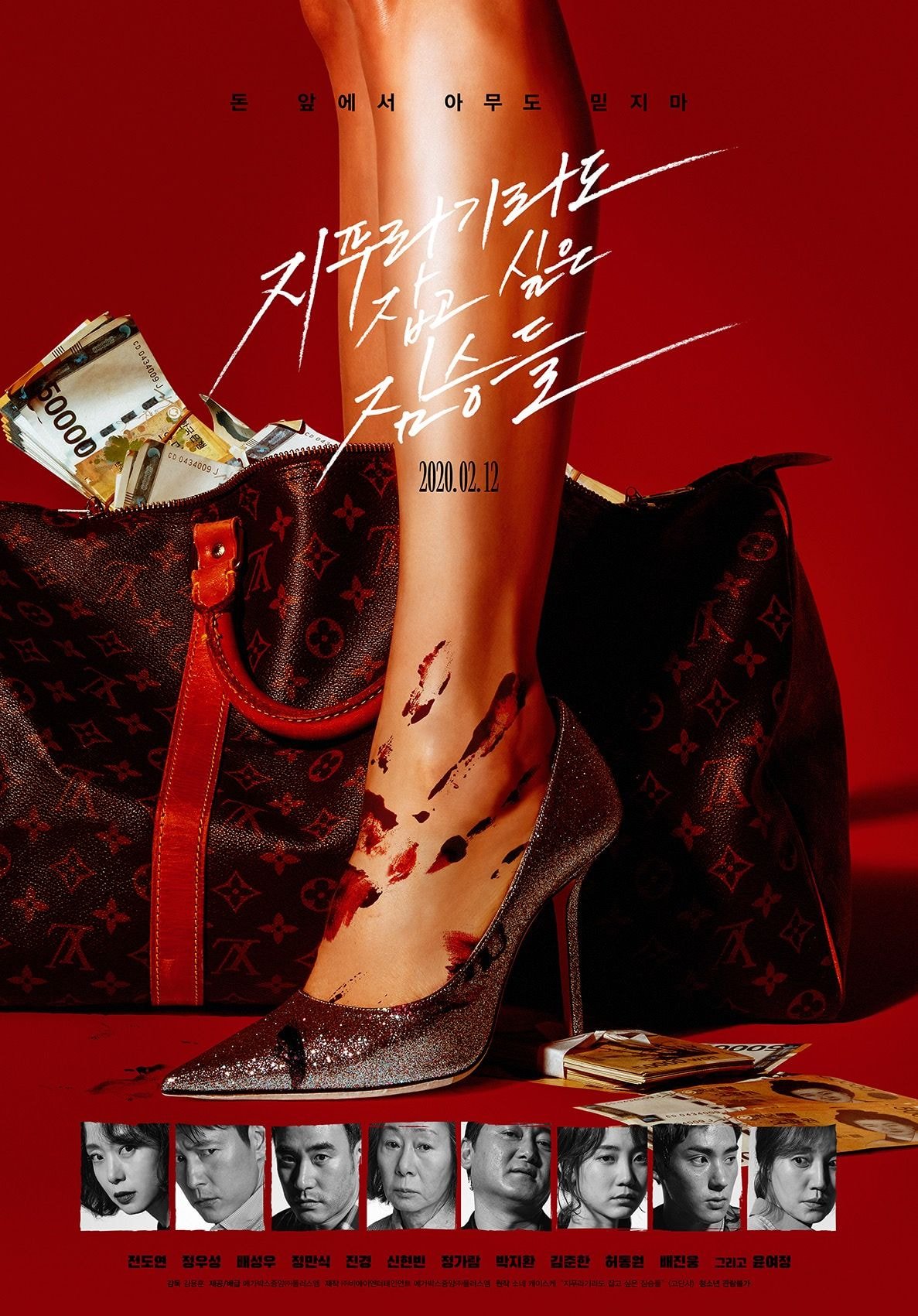

If you found a big bag full of money and then waited a while but no one came to claim it, what would you do? Many people would do as Jung-man (Bae Seong-woo) did, but sometimes gifts from the gods are sent to tempt you and are decidedly more trouble than they’re worth. Beasts Clawing at Straws (지푸라기라도 잡고 싶은 짐승들, Jipuragirado Jabgo Sipeun Jibseungdeul) is an apt way to describe our small group of interconnected protagonists, each desperately trying to get their hands on the money not necessarily for itself but for the power and possibility it represents or simply to free themselves from a debt-laden existence.

Jung-man finds the Louis Vuitton bag stuffed inside a locker at his part-time job in a bathhouse. It seems that he is feeling particularly powerless because he’s somehow lost the family business and either never told his extremely domineering mother (Youn Yuh-jung) or she’s simply forgotten, often going off on crazed rants about how her daughter-in-law is secretly plotting to kill them all. Meanwhile, across town, immigration officer Tae-young (Jung Woo-sung) is desperately trying to find his missing girlfriend, Yeon-hee (Jeon Do-yeon), who has, apparently, run off with all his money leaving him in a difficult position with vicious loan shark Park (Jung Man-sik), and melancholy hostess Mi-ran (Shin Hyun-bin) is miserably trapped in an abusive marriage and plotting escape with the help of Jin-tae (Jung Ga-ram), an undocumented migrant from China she met in the club.

As expected the streams will eventually cross, it is all connected, though it’ll be a while before we start to figure out how in Kim Yong-hoon’s tightly controlled non-linear narrative, adapted from the novel by Japanese author Keisuke Sone. Other than the money the force which connects them is powerlessness. Some of them, maybe all, are “greedy” but it’s not necessarily riches that they want so much as a way out of their disappointing lives. Jung-man feels particularly oppressed because he’s made to feel as if he’s failed his father by losing the family business, something he’s constantly reminded of by his ultra paranoid, domineering mother who eventually pushes his wife down the stairs provoking a crisis point in the foundation of the family. If working part-time in a bathhouse in his 40s hadn’t left him feeling enough of a failure, he is further emasculated by being unable to pay his daughter’s university tuition after she fails to win a scholarship and informs them she’s planning to take a term or two off to earn the money by herself.

Tae-young is in much the same position, humiliatingly trapped by having foolishly co-signed his girlfriend’s loan only for her to disappear off the face of the Earth, leaving him wondering if he’s just a complete idiot or something untoward has happened to her. He thinks he can regain control of the situation by slipping further into the net of criminality, helping an old uni friend who’s committed large-scale fraud escape to China in exchange for a cut of the loot (and secretly plotting to nab the lot with the help of his shady friend Carp (Park Ji-hwan) who works at the club).

A crisis of masculinity is also behind Mi-ran’s life of misery as her husband takes out his resentment towards his reduced circumstances on his wife, beating her mercilessly while forcing her to work at a hostess bar to pay off their debts from unwise stock market investments. For her, the money is both revenge and a pathway to a better life. She wants to be free of her husband, and profit in the process. Unable to do it alone, she manipulates male power in the lovestruck Jin-tae all too eager to play white knight to a damaged woman. But Jin-tae is male failure too. When all’s said and done he’s still an innocent boy, not quite prepared for the ugliness of causing a man’s death even if he is a wife beating tyrant the world may be better off without. As an undocumented migrant, he’s pretty marginalised too. Taking advice on how to solve the Jin-tae problem, a more experienced player reminds Mi-ran that no one’s coming looking for an illegal alien and it’s not as if she actually likes him so he is infinitely expendable.

In an odd way, getting the money is about not being an expendable person anymore. They want the money because they think it will give them back a degree of control over their lives, a kind freedom to move forward with a sense of possibility they do not currently have because of all their debts both financial and emotional. Yet they find themselves farcically scrabbling in chaos, beasts clawing at straws, as they try to outsmart each other and the universe to get their hands on the bag. The universe looks on and laughs, rejoicing in its darkly humorous punchline as the bag finds itself another owner, tempted by its dubious charms with only the promise of more chaos to ensue.

Beasts Clawing at Straws streams in the US via the Smart Cinema app Aug. 29 to Sept. 12 as part of this year’s New York Asian Film festival. Now available in the UK on digital download courtesy of Blue Finch Films!

International trailer (English subtitles)