“Justifying each other’s existence, is that what marriage is about?” Asks top cop Mi-seon (Yum Jung-ah) while contemplating her vaguely dissatisfying marriage to househusband Kang-mu (Hwang Jung-min). In the opening sequences of Lee Myung-hoon’s action rom-com Mission: Cross (크로스), Mi-seon describes Kang-mu as a lottery ticket that’s never going win and suggests she only puts up with him because he’s not the worst man in the world and maybe marriage means putting up with each other. Only on discovering his long-buried secret does she begin re-evaluate him along with what marriage means to her.

Part of what puts her off, however, is Kang-mu’s seeming unmanliness. As a househusband, a rarity in South Korea’s patriarchal society, Kang-mu takes good care of care of her but Mi-seon finds it vaguely annoying and is irritated by his tendency to raid her wallet. It’s also Kang-mu that hosts when her colleagues come over for celebrations after solving a case and he’s got labelled Tupperware in his fridge with homemade kimchi for them. Nevertheless, they all jokingly refer to Kang-mu as Mi-seon’s “missus” which is also in part born of their characterisation of Mi-seon as a man because of her no-nonsense nature and the authority she holds over them. When Kang-mu asks Mi-seon’s colleague Sang-un (Jung Man-sik) to give her a wrist brace he bought her but thinks she’s too proud to accept from him, she jokingly asks if he fancies her but he replies that he only likes women. Nevertheless, Sang-un too is positioned as unmanly because his wife cheated on him which led to their divorce. The other two officers, meanwhile, are obsessed with romantic drama and act out their own version of events after spotting Kang-mu with another woman and becoming convinced that he’s having an affair.

Kang-mu, however, has a secret past as an intelligence officer from which he got fired for conducting an unauthorised mission to stop a Russian arms shipment reaching North Korea. While they were on the boat, they discovered that it was actually going to South Korea while one of his men was killed by the Russian Mafia. Six years later, one of his old colleagues has gone missing while trying to expose a procurement fraud scam run by the mysterious General Park through a fake contract to buy a new aerospace weapon from the Russians. Meanwhile, Mi-seon is investigating the attempted murder of a young woman who was shot after delivering a USB stick containing accounting files to a dead drop.

Obviously, the cases are connected and Mi-seon is about to make a discovery about her husband but not before she experiences the unexpected jealousy of suspecting that he might actually be having an affair. The film actively turns an established trope on its head in that there are countless dramas in which a secret agent thinks he’s married to a regular housewife only to find out she used to be a top assassin, but in its way still ends up conforming to traditional gender roles while essentially subverting them. Mi-seon’s attraction to her husband is reignited when he becomes more stereotypically masculine by charging in with guns and rescuing her. In any case, finding out truth seems to complete the puzzle so that she can reconsider the point of marriage to reflect “Even if the whole world is against you, I’m on your side. That’s what marriage is.”

Even so, the end result is that they fight crime together rather than Mi-seon having to take a back seat while she also commits to making it work rather than being vaguely irritated with Kang-mu but not making any attempt to improve their marriage. Lee cleverly plays with the tropes of the genre to create a genuinely surprising twist complete with a Bond-style maniacal villain playing off the region’s complicated geopolitics by working with the Russians who are thought to be colluding with North Korea against the South when really just in it for themselves. While the final mid-credits sequence, a reference to Hwang’s Netflix series Narco Saints, is a little uncomfortable in its implications, it’s clear that there’s a lot more milage in this potential franchise built around the unusual dynamics of the central pair’s marriage as well as those of Mi-seon’s equally unusual team of lovelorn romantics.

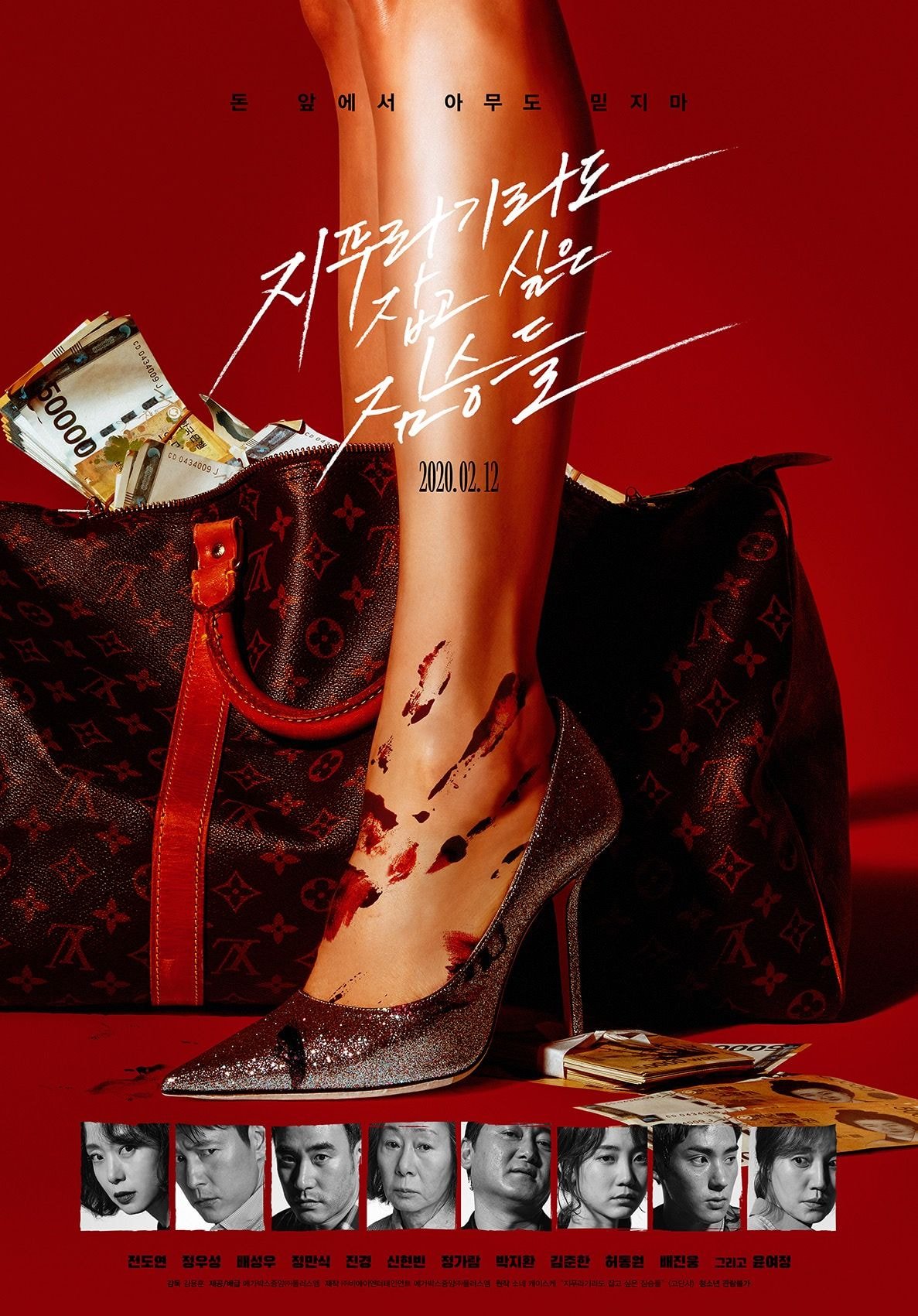

Trailer (English subtitles)