The coming of the railroad spells doom for one of the most prestigious geisha houses in Japan in Hideo Gosha’s adaptation of the Tomiko Miyao novel, The Geisha (陽暉楼, Yokiro). Miyao’s novels had often provided the inspiration for Gosha’s films and she had herself been the daughter of a “flesh broker” in pre-war Kochi though later escaping to another town to be a substitute teacher. Though the English title may more centre plight of the the individual geisha at its centre, the Japanese hints more at the destructive cycle of the Yokiro itself in the persistent legacy of exploitation.

Then again as he later points out, if you’re looking for a villain in this story then the responsibility lies largely with Daikatsu (Ken Ogata) himself. In a prologue set in 1913, Daikatsu has eloped with geisha Otsuru but the pair are discovered by gangsters sent after them by the Yokiro. Daikatsu kills all of their assailants and assures Otsuru that they are finally “free” but it appears to be too late. Holding their baby daughter in one arm, Otsuru collapses into his other and presumably dies either then or shortly after while Daikatsu is later sent to prison for 10 years. 20 years later in 1933, the daughter, Fusako (Kimiko Ikegami), has become the number one geisha at the Yokiro under the name Momowaka though her career flounders because she is regarded as too emotionally distant to keep a patron.

Daikatsu is also himself in Kochi at this point and working as a procurer brokering the sale of young women to the Yokiro and other geisha houses and brothels. When a school teacher comes to him to sell his wife, he taps her teeth to check for malnutrition much as one would examine a horse before running a hand underneath her kimono to check everything is at is should be before offering a valuation. Her husband only looks at him anxiously enquiring if a body such as hers which has as he later reveals born three children will fetch a good price. Daikatsu lets them go so the woman, Masae, can spend a final night with her family explaining that he cannot force someone to work if they do not want to do so and is well aware they will likely take his money and never be seen again which is what almost what happens. As it turns out the husband is killed in a fight and the woman ends up becoming a geisha anyway, only in the pay of prominent Osaka yakuza led by Inaso.

Inaso (Mikio Narita) and buddies want in on the construction of the railroad that will shortly be coming to Kochi, but need to take over the town first which means getting around the mistress of the Yokiro, Osode (Mitsuko Baisho), who is apparently running every game town. The entire local economy is underpinned by female exploitation and facilitated by a woman, a former geisha, seizing the only power that is available to her. Isano later uses Masae as a kind of spy, getting her to initiate a relationship with Osode’s weak willed husband in an attempt to humiliate her which largely backfires as Osode boldly reclaims her man through a violent brawl in a hot spring though it does not appear that she is especially fond of him so much as he serves a particular purpose.

The brawl emphases the way in which women are pitted against each other by the nature of a patriarchal society along with the ways in which they are forced to mediate their power through men. Fusako also gets into an intense physical fight with Tamako (Atsuko Asano), a surrogate daughter of Daikatsu’s and emblem of a coming modernity, who insists on becoming a sex worker at the area’s most prominent brothel. In a strange moment of confrontation, both the geishas of the Yokiro dressed in their traditional regalia, and the sex workers of Tamamizu, arrive at a modern club where the heir to a banking empire courted by the Yokiro, Saganoi, dances the Charleston he learned while studying abroad in America. The geisha who dances with him struggles to pick up the moves, Saganoi lamenting that the dance is just not suited to a woman wearing a heavy kimono, elaborate wig, and clumsy geta. Tamako immediately gets up from her table and kicks off her shoes, gathering the hem of her own kimono to free her legs for the high level kicks of the modern dance.

Fusako reclaims her authority by interrupting the dance immediately before its conclusion and insisting on retrieving their guest. Tamako appears to resent Fusako, perhaps frustrated in her relationship with Daisuke who does not appear to have had much contact with the daughter he sold at 12 years old. They too end up in an elaborate brawl in which Tamako rips off Fusako’s wig and splits her lip, symbolically freeing her to transcend the constraints of her “geisha” persona. Meeting Saganoi at Western-style bar, she boldly dances on the counter and sleeps with him of her own volition. But in doing so she conceives a child and leaves herself in a difficult position. She has betrayed her patron, and though she could simply have kept the fact from him and allowed him to think the baby was his, Fusako does not want to bring her child up in lies while simultaneously hanging on to a naive dream that Saganoi will one day return to her despite being made aware he has left for Europe.

“All men are enemies of women,” she writhes in childbirth while swearing that no one will take her child from her, but she is still an indentured woman and her daughter is by rights the property of Osode. Her illness, presumably consumption, began long before her pregnancy and seems to an echo of the suffering she has been forced to endure as a geisha. As her health weakens, so the Yokiro declines. First it is ravaged by a literal storm, but also under threat from the Osaka gangsters desperate to take over Kochi to gain access to the lucrative construction contracts extending in its direction. Even so, as Daikatsu admits much of the fault lies with him. He chose to elope with Otsuru and was unable to protect either her or their daughter whom he allowed meet the same fate by entering the geisha world. He continued to earn his money by selling women into what is essentially slavery, and cannot escape his part in their continued exploitation while his entanglement with gangsters later disrupts the more settled life Tamako has begun to build for herself.

“Wait all you want, the train’s not coming,” Tamako is later told, as if signalling that there really is no way out of this destructive and disappointing existence. Truly epic in scope, Gosha’s pre-war drama draws together patriarchal exploitation and societal corruption to critique a burgeoning modernity, but ends exactly as it started among the vibrant cherry blossoms only this time undercutting the melancholy of the oft repeated song with a more cheerful scene hinting at least symbolically at a long-awaited reunion.

Original trailer (English subtitles)

Ogami (Tomisaburo Wakayama), former Shogun executioner now a fugitive in search of justice after being framed for treason by the villainous Yagyu clan who are also responsible for the death of his wife, is still on the Demon’s Way with his young son Daigoro (Akihiro Tomikawa). Five films into this six film cycle, the pair are edging closer to their goal as the evil Lord Retsudo continues to make shadowy appearances at the corners of their world. However, the Demon’s Way carries a heavy toll, littered with corpses of unlucky challengers, the road has, of late, begun to claim the lives of the virtuous along with the venal. Conflicted as he was in his execution of a contract to assassinate the tragic Oyuki in the previous instalment,

Ogami (Tomisaburo Wakayama), former Shogun executioner now a fugitive in search of justice after being framed for treason by the villainous Yagyu clan who are also responsible for the death of his wife, is still on the Demon’s Way with his young son Daigoro (Akihiro Tomikawa). Five films into this six film cycle, the pair are edging closer to their goal as the evil Lord Retsudo continues to make shadowy appearances at the corners of their world. However, the Demon’s Way carries a heavy toll, littered with corpses of unlucky challengers, the road has, of late, begun to claim the lives of the virtuous along with the venal. Conflicted as he was in his execution of a contract to assassinate the tragic Oyuki in the previous instalment,  Now four instalments into the Lone Wolf and Cub series, Ogami (Tomisaburo Wakayama) and Daigoro (Akihiro Tomikawa) have been on the road for quite some time, seeking vengeance against the Yagyu clan who framed Ogami for treason, murdered his wife, and stole his prized position as the official Shogun executioner. Lone Wolf and Cub: Baby Cart in Peril (子連れ狼 親の心子の心, Kozure Okami: Oya no Kokoro Ko no Kokoro) is the first in the series not to be directed by Kenji Misumi (though he would return for the following chapter) and the change in approach is very much in evidence as veteran Nikkatsu director Buichi Saito picks up the reins and takes things in a much more active, full on ‘70s exploitation direction. Where

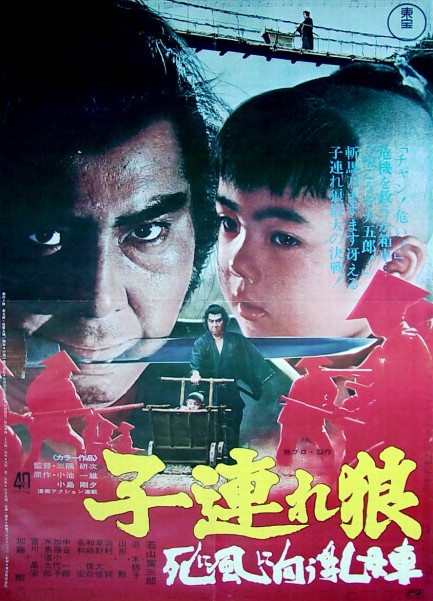

Now four instalments into the Lone Wolf and Cub series, Ogami (Tomisaburo Wakayama) and Daigoro (Akihiro Tomikawa) have been on the road for quite some time, seeking vengeance against the Yagyu clan who framed Ogami for treason, murdered his wife, and stole his prized position as the official Shogun executioner. Lone Wolf and Cub: Baby Cart in Peril (子連れ狼 親の心子の心, Kozure Okami: Oya no Kokoro Ko no Kokoro) is the first in the series not to be directed by Kenji Misumi (though he would return for the following chapter) and the change in approach is very much in evidence as veteran Nikkatsu director Buichi Saito picks up the reins and takes things in a much more active, full on ‘70s exploitation direction. Where  Ogami Itto (Tomisaburo Wakayama) and his (slightly less) young son Daigoro (Akihiro Tomikawa) are going to hell in a baby cart in this third instalment of the six film series, Lone Wolf and Cub: Baby Cart to Hades (子連れ狼 死に風に向う乳母車, Kozure Okami: Shinikazeni Mukau Ubaguruma). The former shogun executioner, framed for treason by the villainous Yagyu clan intent on assuming his position, is still on the “Demon’s Way”, seeking vengeance and the restoration of his clan’s honour with his toddler son safely ensconced within a bamboo cart which also holds its fair share of secrets. In the previous chapter,

Ogami Itto (Tomisaburo Wakayama) and his (slightly less) young son Daigoro (Akihiro Tomikawa) are going to hell in a baby cart in this third instalment of the six film series, Lone Wolf and Cub: Baby Cart to Hades (子連れ狼 死に風に向う乳母車, Kozure Okami: Shinikazeni Mukau Ubaguruma). The former shogun executioner, framed for treason by the villainous Yagyu clan intent on assuming his position, is still on the “Demon’s Way”, seeking vengeance and the restoration of his clan’s honour with his toddler son safely ensconced within a bamboo cart which also holds its fair share of secrets. In the previous chapter,