A clever princess takes advantage of a courtly crisis to save the kingdom and arrange her own marriage in Kozaburo Yoshimura’s adaptation of the well-known kabuki play Narukami, The Beauty and the Dragon (美女と怪龍, Kabuki Juhachiban: Narukami – Bijo to Kairyu), produced in celebration of the 25th anniversary of the Zenshinza kabuki troupe and starring many of its actors. Scripted by Kaneto Shindo, the film mines a deep seam of irony in the classic tale while allowing its heroine to take centre stage outwitting most of the feckless men from the palace with some clever manoeuvring and utilising the key asset of her femininity.

In a meta touch, Yoshimura opens in a kabuki hall where young lord Toyohide (Chiyonosuke Azuma) is called to perform a dance for the regent, Mototsune, only the show is soon interrupted by a procession of peasants who’ve come to protest the ongoing drought. The earth is cracked and the rivers run dry, but still they are told that they will be informed about the outcome of their petition at a later date. The peasants clearly believe that the emperor really is a god and expect him to fix this problem as soon as possible but in private Motosune is irritated if perhaps accurate in stating that the weather is not their responsibility and they can’t seriously be expected to deal with it. Annoyed by the noise of the protests around the palace, he orders that the peasants be sent away though his courtiers are more sympathetic and know that the peasants simply have no one else to turn to for help. If something isn’t done they will have no choice but to escalate their rebellion.

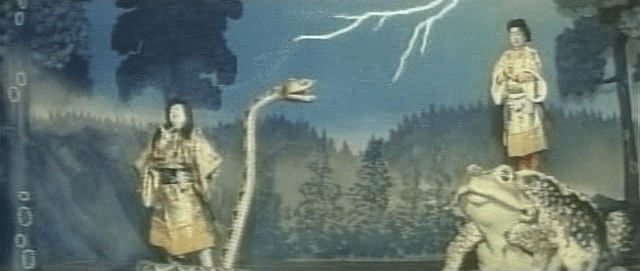

But as it turns out, the problem actually is their responsibility and is rooted in the misogynicistc patriarchy of the feudal world along with a dose of courtly intrigue. When shinto priest Narukami (Chojuro Kawarasaki) was consulted about the birth of a royal child and prophesied that it would be female, he was hired to alter its destiny and miraculously changed its sex to male through the power of prayer. In return, he was promised that a shrine would be built for him but now it’s 30 years later and he’s sick of waiting. Accordingly, he’s taken the Dragon God who brings the rains hostage and refuses to release him so the rain can return until he gets what he was promised.

It seems that Mototsune has a very bad habit of promising people whatever their heart desires but conveniently forgetting about it once the job is done. This time though the problem is that disgraced prince Hayakumo (Kunitaro Kawarazaki) stopped the building of the shrine in fear of offending a rival temple, Ezian, which contains a large number of very intimidating bandit monks. Hayakumo is intent on using the courtly chaos to improve his own position, hoping that other lords will fall from favour leaving a space for him to fill. He’s also been obsessively courting princess Taema (Nobuko Otowa) who refuses him because he’s so obviously oily, and in any case she’s in love with Toyohide but can’t marry him seeing as he is already betrothed to another woman whom he does not care for. In a bizarre twist of fate, a scholar insists that the only way to break Narukami’s magic is by learning to read a scroll that once belonged to Taema’s grandfather so they charge her with deciphering it offering to give her whatever her heart desires if she ends the drought which is of course Toyohide’s hand in marriage.

The ironic thing is that Taema doesn’t for a second believe that reading the scroll will make any difference to anything and quite clearly thinks the scholar they brought in who said it would is a charlatan who actively looks down on her. Yet she, like everyone else, does in fact believe that the cause of the drought is the Dragon God’s imprisonment and Narukami’s dark magic. Advised by her trusty maid, she learns to see opportunity in what could otherwise be a dangerous situation and ably out manoeuvres the foolish men at the court. She wields her femininity, the reason they discount her, as a weapon against the repressed masculinity of Narukami who is said to have been a monk since childhood and has never touched a woman.

After getting her maid to do a sexy dance for his underlings so that they get drunk and pass out, she then sells Narukami a tragic love story pretending that she simply wants to wash some clothes that belonged to her late husband. Essentially she seduces him, but also targets his weakness in his repressed desires as a monk causing him to transgress his vows and in effect break his own magic by destroying his powers. On seeing her bared ankles he faints, and then ends up telling her how to break the curse after becoming drunk and randomly assuming they are now married.

As she’d somewhat dangerously told Toyohide, the real problem is that the Regent is weak. Indifferent to the fates of his people and in any case an ineffective leader, he invites intrigue in the court. Yet court itself is weak precisely because it is rooted in patriarchy and defined by male weakness. Even Taema’s beloved Toyohide is preening and jealous, suddenly irritated to discover that Hayakumo had been courting her while later suspicious that she will be alone with Narukami. He was also denied romantic freedom in an inability to escape the marriage arranged for him by his father at three and reliant on Taema finding a way for them subvert the feudal order and be together. The play in fact ends with the rage of a scorned man as the aptly named Narukami is transformed into the god of thunder and vows vengeance against the woman who humiliated him.

Taema, by contrast, is able to seize control ridding herself of Hayakumo while securing her marriage to a man she choses (the betrothed bride is herself similarly freed and appears not to mind the dissolution of her engagement having had no particular feelings for Toyohide, a man she barely knew) in addition to saving the kingdom along with the lives of peasants by unleashing the Dragon God. Having begun in the theatre, Yoshimura soon moves out to the court and then the country but eventually cycles back for the climactic dance of anger with which the film closes as if echoing a howl of pain from the wounded feudal era circumvented, if not ended, by a clever woman leveraging her only sources of power in a world defined by corrupted male authority.