Charged with the responsibility of saving the world, a teenage girl wonders if she should in Kazuaki Kiriya’s pre-apocalyptic drama, From the End of the World (世界の終わりから, Sekai no Owari kara). After all, the suffering will continue. People will continue to be cruel and selfish. Maybe it’s better to let humanity fizzle out and least save the planet. But really whether any of this is “real” or not, what’s she’s looking for is an escape from her grief and loneliness and a world that is a little kinder and less self-destructive.

Shortly after losing her grandmother, who had been raising her after her parents were killed in a car accident, Hana (Aoi Ito) begins having strange dreams where she’s cast back to what seems to be feudal Japan where she meets a young indigenous girl whose family have been wiped out by marauding samurai. The girl’s guardian, an older woman (Mari Natsuki), explains to her that her arrival in this place has been foretold by some kind of scripture painted on the ceiling of a cave and that her duty is to deliver a letter to a shrine. Not too long later, she’s accosted by some kind of mysterious authority which seems very interested in her dreams, eventually taking her to a strange base in another cave where she meets an old woman (also Mari Natsuki) who looks exactly like the one saw in her dream. The world will apparently end in two week’s time, though she alone has the ability to alter what has been written through the power of her dreams which allows her to change people’s thoughts and thereby rewrite their destiny.

She does not do this deliberately, but reacts instinctively to the events she encounters which the old woman claims exist in the “Sea of Sentiment”, a great confluence of human thought on which the world is built. “Understanding things is overrated. Everything’s an illusion. What’s important is your feelings,” another mysterious presence (Kazuki Kitamura) tells her, a man who exists between dream and reality and would rather the world end because as long as it exists he cannot die. In some respects, he may represent Hana’s depression suggesting that to continue to live is only to prolong her suffering and that it’s better for everyone to simply give in and let fate take its course while she weighs up kindness and vengeance using her newfound powers for “selfish” reasons to end the torment she’s been suffering at the hands of a bullying classmate who’s long been blackmailing her in taking advantage of her precarious position as a financially disadvantaged orphan.

The quest that the old woman sends her on is really into the depths of her own heart which is wounded not only by a medical issue she seems to have forgotten but a pair of childhood traumas buried behind a door she did not want to open. The real message that she’s supposed to deliver has its own paradoxical sense of poignancy, “from the end of the world to you in the future”, which signals her nihilism and despair but also a desire for some kind of continuation or rebirth in a better, kinder world less marked by suffering or selfishness. Then again, the way of achieving that world is still rooted in violence only of a more knowing kind that heads off one particular kind of disaster and allows Hana to save “herself” in all her incarnations, but perhaps doesn’t do very much to change the human “foolishness” to which the old woman ascribes humanity’s destruction.

Logically, it doesn’t quite hang together and not all of it makes sense (understanding things is overrated), but it has its own kind of internal consistency even if at times somewhat incoherent as it well might be if it were all the dream of a lonely teenage girl who’s given up on the idea of a future for herself because her life has been too full of suffering and unfairness. It’s no coincide the date of the end of the world is set for the same day as her high school graduation ceremony. Her world really is ending if in a less literal way leaving her all alone and forced into a more concrete adulthood while her peers get to chase their dreams a little longer by moving on to higher education while she’ll have to look for work to support herself. She may feel that nothing she does makes any difference and that she is powerless to change her fate, but also realises that she is not as alone as she thought. Featuring top notch production values and some striking production design, Kiriya’s sci-fi action drama is quietly touching in its final resolution that despite everything Hana still wants to love the world even if it’s making it very difficult.

From the End of the World screens in New York Aug. 5 as part of this year’s JAPAN CUTS.

Teaser trailer (no subtitles)

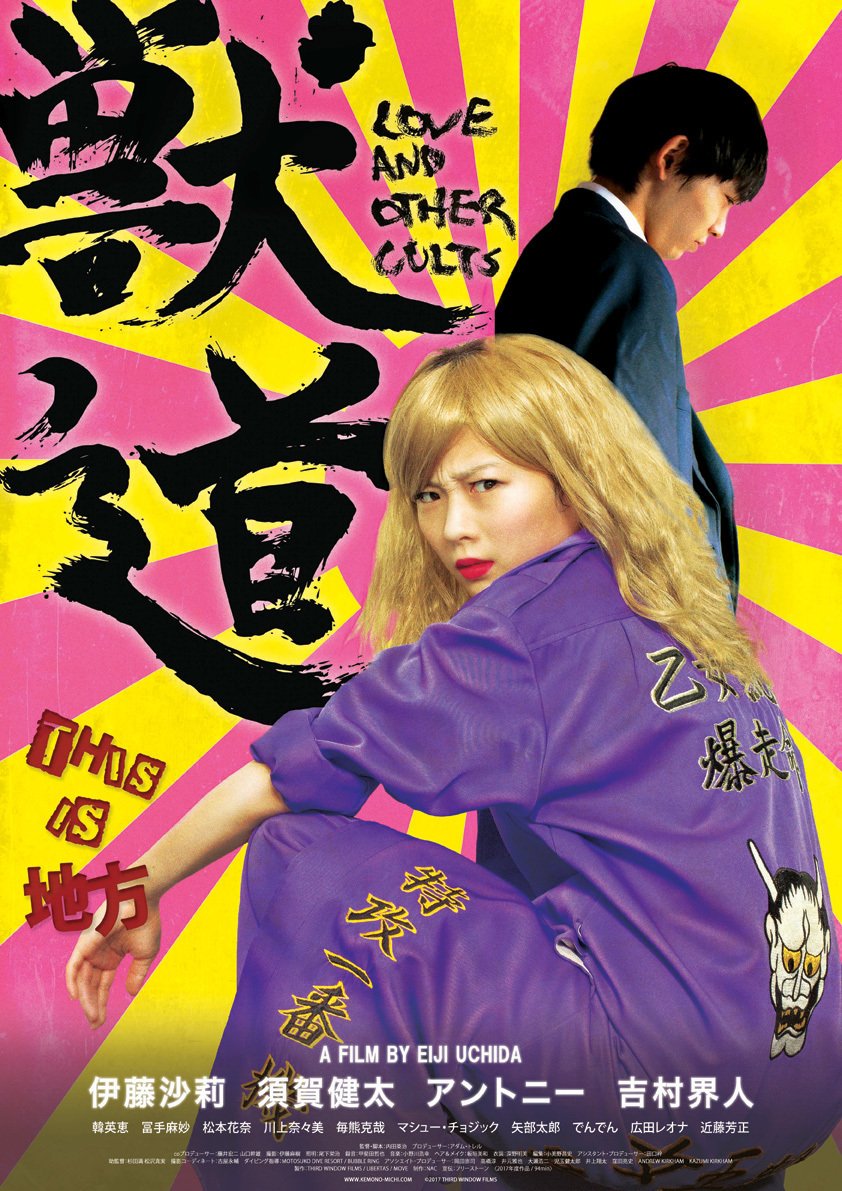

Eiji Uchida’s career has been marked by the stories of self defined outsiders trying to decide if they want to move towards or further away from the centre, but in his latest film Love and Other Cults ( 獣道, Kemonomichi), he seems content to let them linger on the margins. The title, neatly suggesting that perhaps love itself is little more than a ritualised set of devotional acts, sets us up for a strange odyssey through teenage identity shifting but where it sends us is a little more obscure as a still young man revisits his youthful romance only to find it as wandering and ill-defined as many a first love story and like many such tales, one ultimately belonging to someone else.

Eiji Uchida’s career has been marked by the stories of self defined outsiders trying to decide if they want to move towards or further away from the centre, but in his latest film Love and Other Cults ( 獣道, Kemonomichi), he seems content to let them linger on the margins. The title, neatly suggesting that perhaps love itself is little more than a ritualised set of devotional acts, sets us up for a strange odyssey through teenage identity shifting but where it sends us is a little more obscure as a still young man revisits his youthful romance only to find it as wandering and ill-defined as many a first love story and like many such tales, one ultimately belonging to someone else.