“A death is a history” runs an opening title card in Nobuhiko Obayashi’s poignant existential drama, Seven Weeks (野のなななのか, No no Nanananoka). Returning to some of the director’s key themes, Obayashi’s adaptation of the novel by Koji Hasegawa takes its name from the traditional Buddhist period of mourning reminding us that life and death is a continuous cycle in which all lives are necessarily tied to one another. Some may later ask if those connections are also constraints, thinking perhaps of the sometimes onerous burdens of family, but even they later reflect on the necessity of human ties while contemplating the confluence of the eternal and the transient.

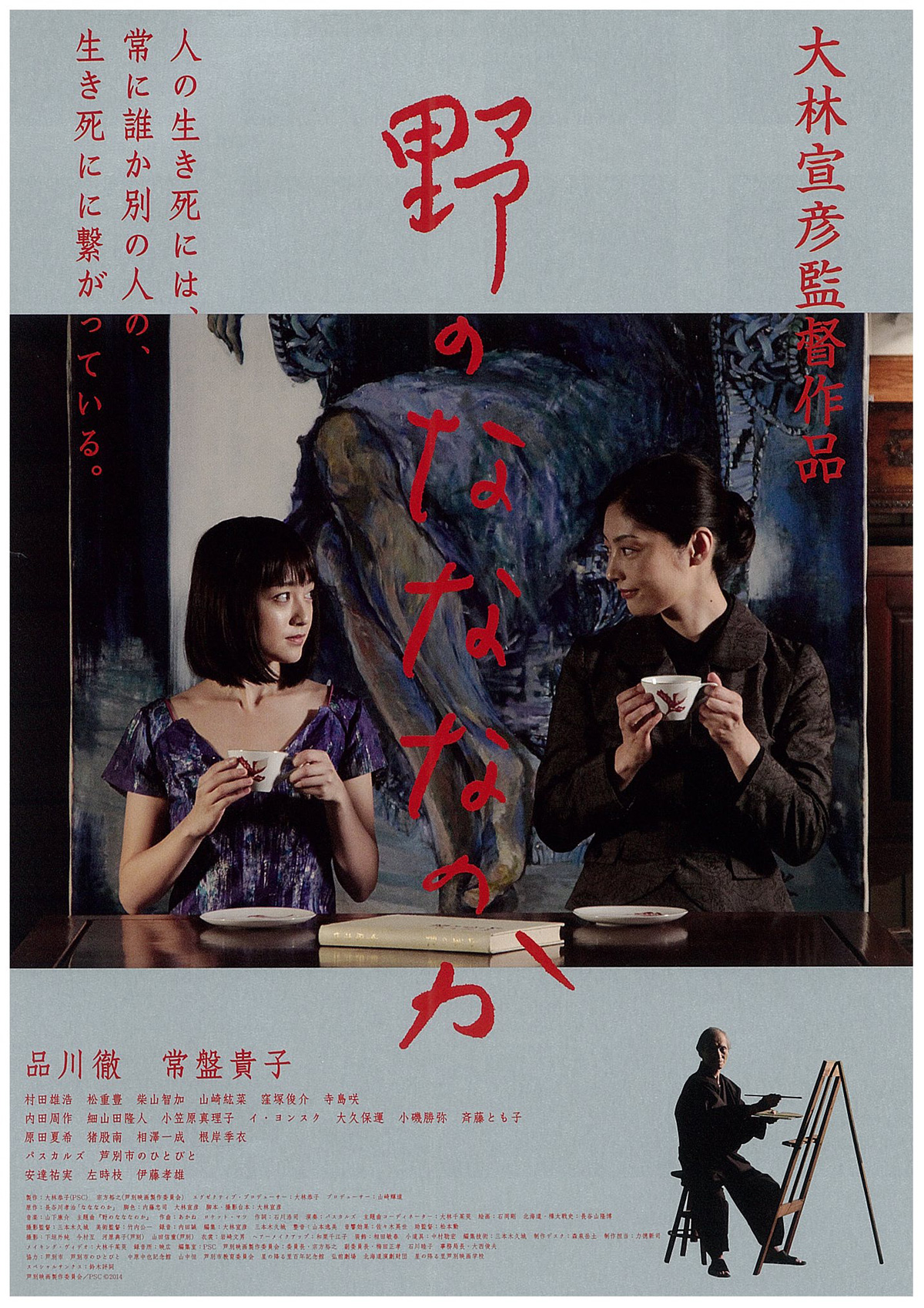

The death we’re being asked to witness is that of 92-year-old Mitsuo Suzuki (Toru Shinagawa), a former doctor and owner of what some view as a junk shop, who is discovered collapsed by his granddaughter Kanna (Saki Terashima) only to die a few days later at the time shown on his permanently broken wristwatch which also happens to be the time the Great East Japan Earthquake struck in 2011. Soon his extended family begin to arrive beginning with long widowed sister Eiko (Tokie Hidari), grandson Fuyuki (Takehiro Murata) and his daughter Kasane (Hirona Yamazaki), and Kanna’s brother Akito (Shunsuke Kubozuka) while Fuyuki’s brother Haruhiko (Yutaka Matsushige) and his wife Setsuko (Tomoka Shibayama) will make it only in time for the wake. Throwing all into confusion is the unexpected arrival of a mysterious young woman, Nobuko (Takako Tokiwa), later revealed to be a nurse who once lived with the family and fulfilled the role of mother for Kanna and Akito whose parents were killed in a car accident while they were still young.

Nobuko is in many ways the key to a mystery yet also a cypher, more than one woman at the same time as if in a sense resurrected from Mitsuo’s traumatic memories of love and war in the time of his youth. At his wake, men of a similar age spin their own war stories, Eiko reminding the young that their youth was war and perhaps they’ve a right to romanticise it for all of its terrible cruelty. Mitsuo didn’t go to the front but found himself a victim of shifting borders, ironically a descendent of settler colonisers as a native of Hokkaido travelling to the disputed island of Sakhalin in search of a friend and in the company of the young woman who was engaged to him but with whom he was himself in love believing the war was over only to discover no one had told the Russians and that wars do not end at the same time for everyone, or for some at all.

In an ironic touch, great-granddaughter Kasane participates in an excavation of an old mine once staffed largely by forced Korean labour, an elderly woman plaintively singing Arirang over the dig site, only to later visit a similar location which has become the “Canada World” tourist attraction including a replica of the house from Anne of Green Gables. As she, Eiko, and Kanna reflect on the changes in the town there’s a minor sadness that the mine has closed which seems somewhat incongruous, even as the wholesomeness of coal from the ground is favourably compared with the dangerously intangible qualities of nuclear energy. Nevertheless, conflicted nuclear engineer Haruhiko later stakes his future on renewable energy, neatly echoing the sense of circularity in a continuous cycle of death and rebirth in which one life is necessarily tied to another and therefore to all lives.

“We got along with the Russians in Sakhalin before the war” Mitsuo’s friend Ono (Takao Ito) laments, musing on the senselessness of conflict in its propensity to draw lines between people which divide rather than connect. Mitsuo’s death is indeed “a history tying the past and future”, a minor allegory for that of his nation as he contemplates lost love and the end to wandering that is death which leads in turn to new beginnings. “You want to look away. You want to forget about it”, Mitsuo confesses, “but you can’t. You have to remember so that it’s never repeated”. Through their 49-day odyssey, the family members begin to edge their way towards a less anxious if still uncertain future. “We might lose people but not hope” Kanna expounds, recommitting herself to the hometown spirit while opening up to the possibility of romance, while her brother does something much the same, as does her uncle Fuyuki even as his daughter conversely gives up on a possibly inappropriate crush to shift into a more mature adulthood. “We will go on peacefully” runs the final title card, a mission statement for the foundation of a better world.

Seven Weeks streams in the US July 9 – Aug. 6 as part of Japan Society New York’s Tragedies of Youth: Nobuhiko Obayashi’s War Trilogy season in collaboration with KimStim.

Original trailer (English subtitles)