Though there’s a clear divide between the first three films in the Shinobi no Mono series and those that followed, one thing that remained constant is that time passed. By the sixth instalment, we’re already in 1637 which is more than 50 years after the setting of the first film which began in 1575 at the tail end of the Warring States era. Hero of films four and five, Saizo had been desperate to return to the chaos of the pre-Seikgahara society in which the ninja could indeed hold sway though as he discovered the pax Tokugawa was definitely here to stay.

Given that Saizo would now be an old man, the torch is passed to his son, Saisuke (Raizo Ichikawa), who like his father opposes the Tokugawa but also has a desire for revenge against the corrupt petty official who killed him during the battle of Shimabara which definitely sealed the Tokugawa victory. Ieyasu may be dead, but the regime has only become more oppressive while it seems there is still enough intrigue to provide work for the jobbing ninja only now it’s taking place largely within the palace in the de facto one party state of the feudal society.

On the other hand, there is a degree of destabilisation and societal flux as the old class system struggles to adjust to a world of peace. The nation is filled with disenfranchised samurai and ronin who largely have no real options to support themselves other than becoming mercenaries or taking odd jobs from various lords in the hope of eventually being taken in as a permanent retainer. It’s these ronin that Saisuke, and the rebellion’s leader Yui Shosetsu (Mizuho Suzuki), hope to marshal in convincing them to rise up against Tokugawa oppression and regain at least a little of the freedom their immediate forebears enjoyed.

The evils of this system can be seen in an otherwise sympathetic lord’s insistence that his underling will have to take the blame and commit seppuku if his decision to help the rebels is discovered. As Saisuke later remarks, the era of human knowledge rather than weaponry is already here and battles are largely being fought over parlour games played in court. At this point, the shogun’s sudden demise leaving only an 11-year-old son has opened a power vacuum that allows unscrupulous lords, like Saisuke’s enemy Izu (Isao Yamagata), to exercise power vicariously. Izu has used it to enrich himself by exploiting desperate ronin and spending vast sums on personal projects, yet he proves himself a true politician in effortlessly covering up for the lord who tried to help the rebels doubtless knowing that he now has him in his pocket for life.

Seemingly returning to the low-key social principles of the first few films, Saisuke’s rebellion is also towards the inherently unfair system complaining that the battle for power is a monster that feeds on courage and will crush conscience like an insect. But as Izu says, times have changed and the struggle cannot be ended even if Saisuke argues that anything manmade can be dismantled. Saisuke has to admit that he’s been outplayed, the leader of the revolution also turns out to be corrupt, taking advantage of other people’s desperation and dissatisfaction to enrich himself while Izu’s plotting has left him largely blindfolded as a ninja clearly out of his depth in the new and confusing world of the Tokugawa hegemony. A powerful man is always looking for a victim, he reflects, perhaps echoing the plight of Goemon unwittingly manipulated by the duplicitous Sandayu while admittedly somewhat drunk on his own misplaced sense of self-confidence.

Deviating a little from the realism of the series as a whole, the film shifts into more recognisably jidaigeki territory revolving around corrupt lords and an exploited populace even if in this case it’s the disenfranchised warrior class experiencing a moment of mass redundancy though apparently unwilling to resist. Peep holes behind noh masks add a note of quirky innovation to the backroom machinations of the Tokugawa regime while silent ninja battles and flaming shuriken add to the sense of noirish danger even as it becomes clear that the ninja is approaching a moment of eclipse, no longer quite necessary in a world of constant duplicity.

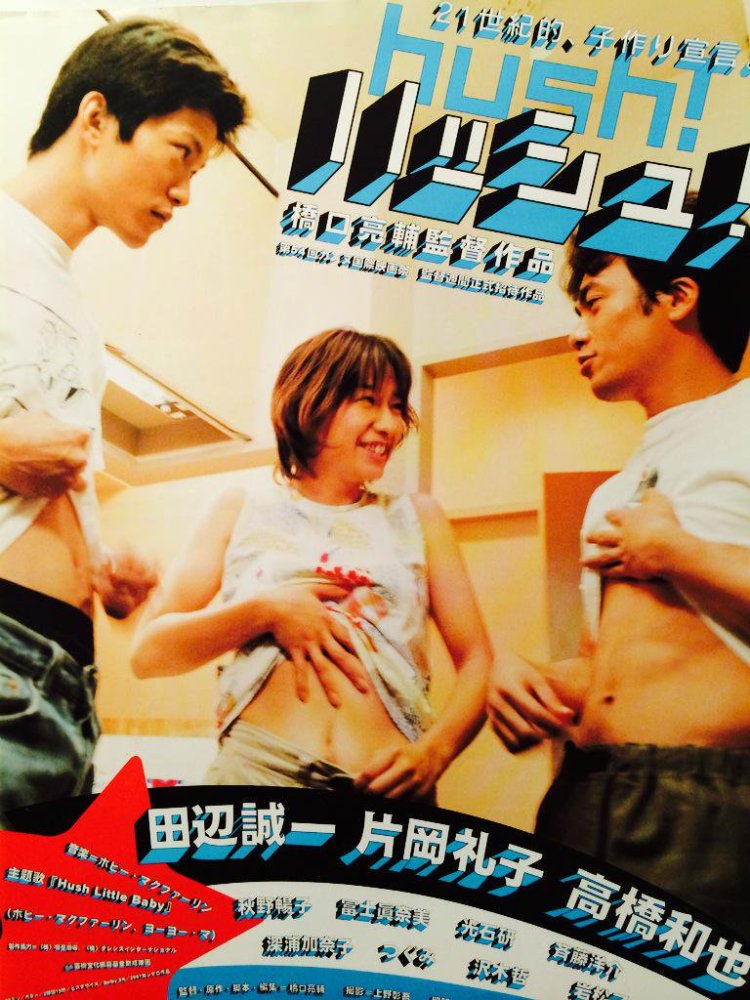

The family drama is a mainstay of Japanese cinema, true, but, it’s a far wider genre than might be assumed. The rays fracture out from Ozu through to

The family drama is a mainstay of Japanese cinema, true, but, it’s a far wider genre than might be assumed. The rays fracture out from Ozu through to