“For us the natural world is a playground. But for the things that live in it, it might be hell on earth.” a middle-aged stranger explains to a confused teenage boy elaborating on a metaphor about a strangler tree that wraps itself around its brethren and suffocates them to death. The contemporary society is indeed a hell on earth to the alienated turn of the century teens in Shunji Iwai’s plaintive youth drama All About Lily Chou-Chou (リリイ・シュシュのすべて, Lily Chou-Chou no Subete) who have found solace in “The Ether”, “a place of eternal peace” as discovered in the music of a zeitgeisty pop singer inspired by the ethereality of Mandopop star Faye Wong.

Filled with millennial anxiety, The Ether as mediated through message board chat is the only place the teens can be their authentic selves. “For me only the Ether is proof that I’m alive” one messenger types using an otherwise anonymous online handle unconnected with their real life identity. Iwai often cuts to the teens standing alone listening to music on their Discmans while surrounded by verdant green and wide open space with a bluer than blue sky above, but also at times finding that same space barren and discoloured, drained of life in, as Yuichi (Hayato Ichihara) puts it, an age of grey much like a field in winter. For Yuichi the world ended on the first day of school in September 1999 when his torment began at the hands of a previously bullied boy who decided to turn the tables after, of all things, getting hit in the head by a flying fish in Okinawa and almost drowning.

Purchased with money stolen from some other bullies who had just stolen it from a well-off middle-aged man they were harassing in a carpark, the trip to Okinawa captured in grainy ‘90s holiday video style later subverted by the same use of contemporary technology to film a gang rape of a fellow student, is the event that finally reduces Yuichi’s world to ashes. Like the other teens he is also carrying a sense of alienation as his mother prepares to remarry while carrying his soon-to-be stepfather’s child which also dictates that Yuichi will have to change his surname lending a further degree of instability to his already shaky sense of identity. For Hoshino (Shugo Oshinari), his sometime friend, the instability seems to run a little deeper. “Nobody understands me” he tells Yuichi with broody intensity, irritated by the image others have of him as a top swat chosen to give a speech at the school’s opening ceremony and widely believed to have placed first in the exams. In truth he only placed seventh and is most annoyed that whoever really did come top probably thinks he pathetically lied about it for clout.

We can see that Hoshino’s family appears to be wealthy, at least much more than Yuichi’s, though as we also discover they once owned a factory which has since gone bust amid the economic malaise of the ‘90s leading to the disintegration of his family unit. Like Yuichi he feels himself adrift, evidently bullied in middle school for being studious and introverted while rejected by the girls in his class who again attack him because of his model student image. Hoshino seems to have a crush on a girl who is herself bullied, Kuno (Ayumi Ito), apparently resented by the popular set for being popular with boys. “It’s amazing how women can ostracise someone like that” band leader Sasaki (Takahito Hosoyamada) reflects, one of the few willing to call her treatment what it is but finding no support from their indifferent teacher Miss Osanai (Mayuko Yoshioka), while entirely oblivious to the fact that the boys are just the same in Hoshino’s eventual reign of terror as a nihilistic bully drunk on his own illusionary power.

Shiori (Yu Aoi), blackmailed into having sex with middle-aged men for money, questions why she and Yuichi essentially allow themselves to be manipulated by Hoshino and are unable to stand up to him even when they know they are being asked to do things that they find morally repugnant such as Yuichi’s complicity when tasked with setting Kuno up for gang rape by Hoshino’s minions with a view to videoing it for blackmail purposes. Whether or not he did in fact have a romantic crush on her, Hoshino’s orchestration of the rape signals his total transformation, forever killing the last vestiges of his humanity and innocence but for Yuichi, who can only stand by and cry, it signals the failure of his resistance that if he went along with this there is no line beyond which he will not go if Hoshino asks it. Yuichi asks Shiori why she didn’t agree to date the kindhearted Sasaki who would have been able to shield her from Hoshino but she knows it’s too late for that while suggesting Yuichi is in a sense protecting her though his inability to do so only further erodes his wounded sense of masculinity.

Only online can the teens find the elusive Ether they dream of, ironically connected via a message board that Yuichi runs under the name Philia where the only rule is that you have to love Lily yet unknown to each other thanks to the alienating effect of their online handles. Someone has a point when they suggest all this talk of polluting the Ether sounds a bit like a cult, but does at least give the teens their safe space where they can share their pain free of judgement and find solidarity in adolescent angst. In any case all of this shame, repression, and loneliness is later channeled into nihilistic violence and cruelty provoked by millennial despair. The only way Yuichi can free himself is by killing the part of himself that hurts in an effort to quell the “noise” in his head. Broken by title cards accompanied by the reverberating sound of typing in emptiness, Iwai’s characteristic soft focus lends a trace of nostalgic melancholy to this often harrowing tale but also neatly encapsulates turn of the century teenage angst with the infinite sympathies of age.

All About Lily Chou-Chou screens at Japan Society New York on Dec. 10 as part of Love Letters: Four Films by Shunji Iwai

Original trailer (English subtitles)

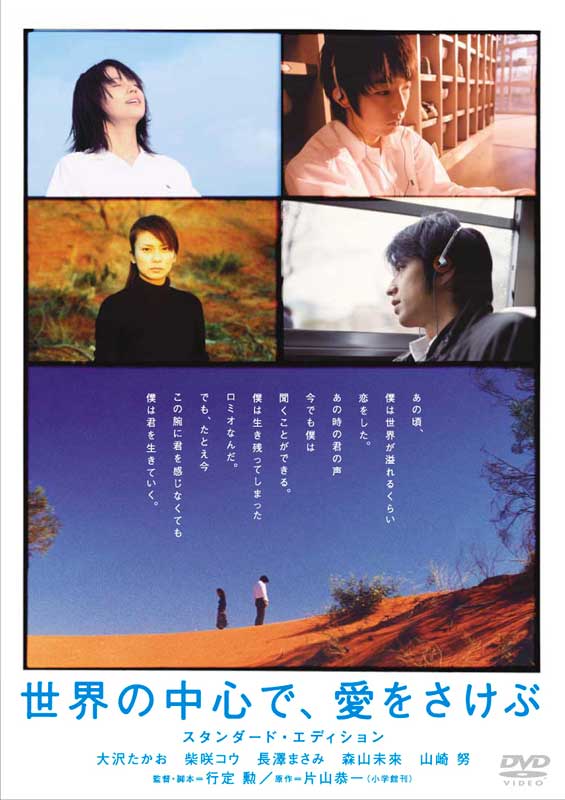

Just look at at that title for a second, would you? Crying Out Love, in the Center of the World, you’d be hard pressed to find a more poetically titled film even given Japan’s fairly abstract titling system. All the pain and rage and sorrow of youth seem to be penned up inside it waiting to burst forth. As you might expect, the film is part of the “Jun ai” or pure love genre and focusses on the doomed love story between an ordinary teenage boy and a dying girl. Their tragic romance may actually only occupy a few weeks, from early summer to late autumn, but its intensity casts a shadow across the rest of the boy’s life.

Just look at at that title for a second, would you? Crying Out Love, in the Center of the World, you’d be hard pressed to find a more poetically titled film even given Japan’s fairly abstract titling system. All the pain and rage and sorrow of youth seem to be penned up inside it waiting to burst forth. As you might expect, the film is part of the “Jun ai” or pure love genre and focusses on the doomed love story between an ordinary teenage boy and a dying girl. Their tragic romance may actually only occupy a few weeks, from early summer to late autumn, but its intensity casts a shadow across the rest of the boy’s life. Originating as an ongoing manga series by Akiko Higashimura which was also later adapted into a popular TV anime, Princess Jellyfish adopts a slightly unusual focus as it homes in on the sometimes underrepresented female otaku.

Originating as an ongoing manga series by Akiko Higashimura which was also later adapted into a popular TV anime, Princess Jellyfish adopts a slightly unusual focus as it homes in on the sometimes underrepresented female otaku.