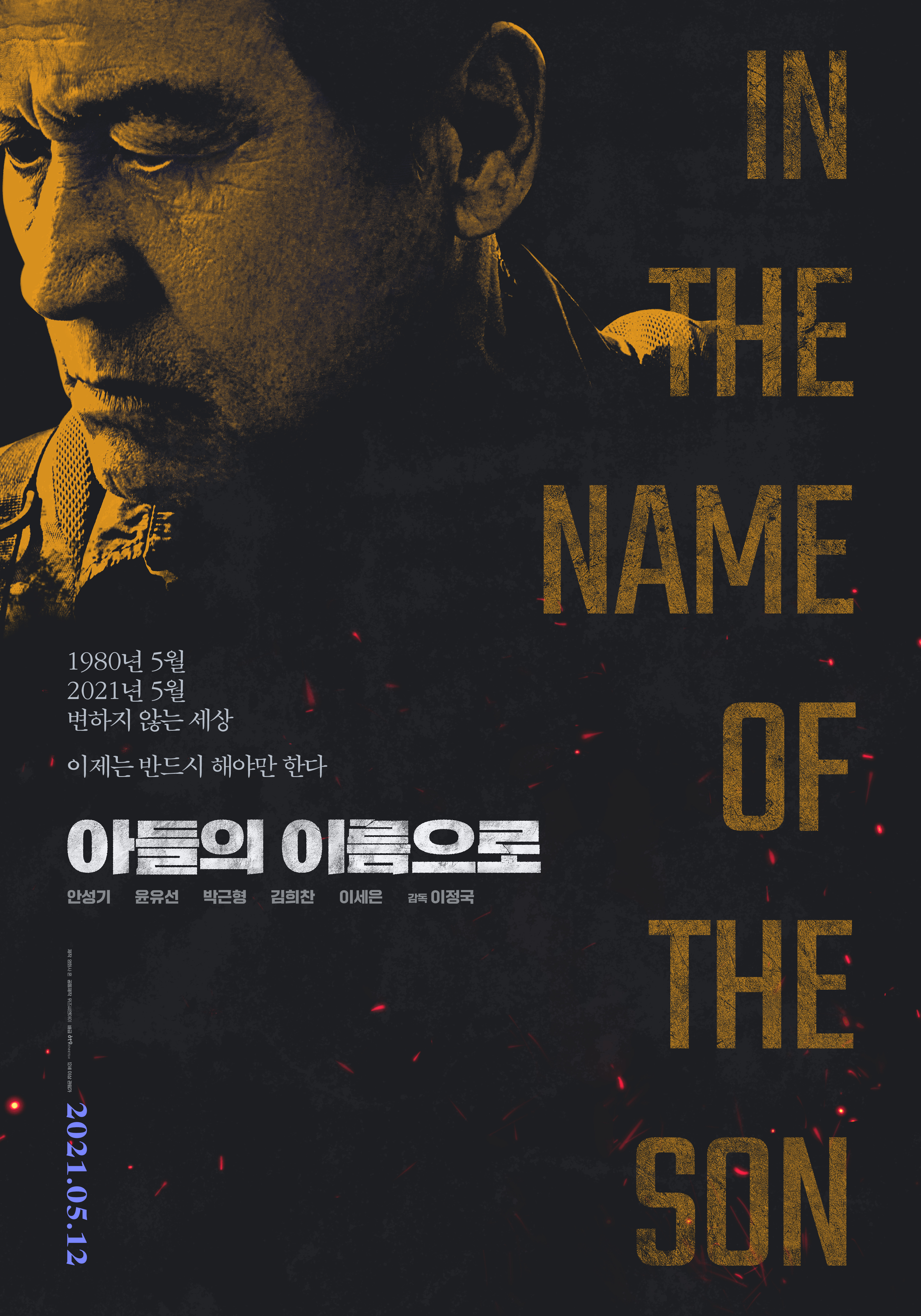

Partway through Lee Jung-gook’s raw exploration of the radiating effects of historical trauma In the Name of the Son (아들의 이름으로, Adeurui ireumeuro), the conflicted hero quotes a line from In Search of Lost Time which his son had recommended to him, “pain is only healed by thoroughly experiencing it”. The quote in itself reflects the hero’s wounded state in having failed to reckon with the sins of the past, a failing which has cost him dearly on a personal level, while simultaneously hinting at a national trauma which has never been fully addressed by the contemporary society.

When we first meet ageing designated driver Chae-gun (Ahn Sung-ki) he’s preparing to hang himself in a forest before noticing a stray parakeet, presumably an escaped family pet, chirping nearby in desperation. Taking pity on the bird knowing it cannot survive on its own he gives up on his plans and takes it home. We can see that Chae-gun is a compassionate man, softly spoken, perhaps a little shy and distant yet caring deeply for those around him such as the ladies from Gwangju who run a cafe where he is a regular, while he’s frequently seen making phone calls to his son in America. Yet as we later discover he is also a man of violence with an old-fashioned, authoritarian mindset, ominously sliding off his belt to beat up a gang of kids who tried to dine and dash before making them come back to apologise and pay their bill and later doing the same to bullying classmates of the cafe owner’s son, Min-woo (Kim Hee-chan).

He does these things less out of an old man’s disapproval of the younger generation’s lack of moral fibre than a genuine desire to help and most particularly the ladies at the cafe, but simultaneously takes Min-woo to task for a lack of manliness berating him in front of his bullies for not standing up for himself. These flashes of violence hark back to the hyper-masculine patriarchal attitudes that defined the years of dictatorship while also hinting at the buried self Chae-gun struggles to accept which so contrasts with his innate kindness and sense of justice. He too is angry and confused that those who ordered acts of atrocity such as the 1980 Gwangju Massacre have never been brought to justice and are living comfortable lives often still ensconced in country’s ruling elite such as former general Chairman Park whom he often drives home from a local Japanese restaurant to his mansion in a traditional village in the middle of Seoul.

As we discover, Chae-gun has his own reasons for being preoccupied with Gwangju in particular, yet it’s the failure to reckon with the buried past that he fears erodes future possibility. In a metaphor that in truth is a little overworked, one of the new assistants at the cafe, also from Gwangju, is mute, literally without a voice until the buried truths of the massacre are symbolically unearthed allowing her to speak. Meanwhile, many of Chae-gun’s generation are succumbing to dementia, an elderly man constantly escaping from his nursing home to wander a local park looking for his teenage son who went missing during the uprising and was never seen again. Chairman Park remains unrepentant, blaming everything then and now on “commies” while explaining to Chae-gun that they were “patriots” not “murderers” bravely defending the Korean state and in any case God forgives all so they’ve no need to blame themselves.

Park may feel no remorse but the unresolved trauma of Gwangju continues to echo not only through Chae-gun’s wounded soul but through society, a heated debate breaking out between a group young people of critical of the authoritarian past and a collection of older conservative nationalists who object to their criticism of President Park Chung-hee arguing that he rebuilt the economy and gave them the comfortable lives they live today. Yet what Chae-gun feels he owes to his son and implicitly to the younger generation is an honest reckoning with the past and his part in it while those who live with no remorse should not be allowed to prosper, guilt-free, as victims continue to suffer. What he’d say to those who thought that they bore no responsibility is that the greatest sin of all may have been in blindly following orders. Only by fully experiencing the pain of the national trauma can society hope to heal itself from the weeping wounds of the unresolved past.

In the Name of the Son streamed as part of the 14th season of Asian Pop-Up Cinema.

Original trailer (English subtitles)