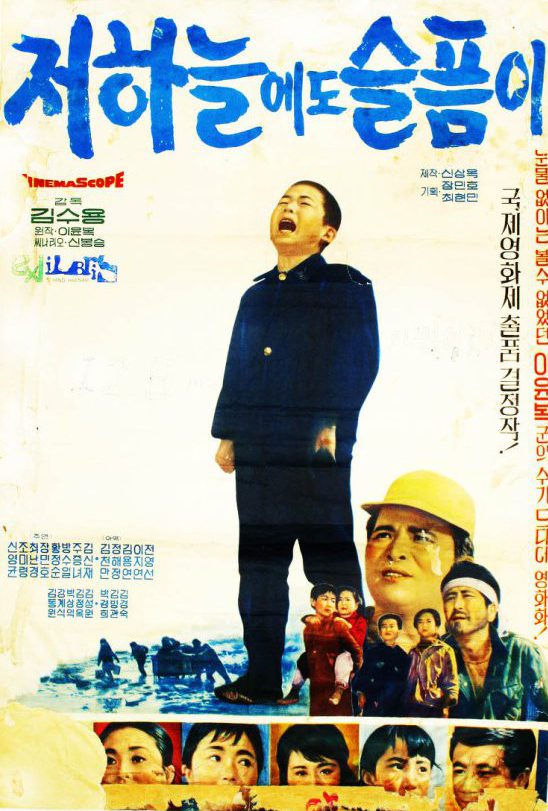

It’s a sorry enough tale to hear that many silent classics no longer exist, regarded only as disposable entertainment and only latterly collected into archives and preserved as valuable film history, but in the case of South Korea even mid and late 20th century films are unavailable thanks to the country’s turbulent political history. Though often listed among the greats of 1960s Korean cinema, Sorrow Even Up in Heaven (저 하늘에도 슬픔이, Jeo Haneuledo Seulpeumi) was presumed lost until a Mandarin subtitled print was discovered in an archive in Taiwan. Now given a full restoration by the Korean Film Archive, Kim’s tale of societal indifference to childhood poverty has finally been returned to its rightful place in cinema history but, as Kim’s own attempt to remake the film 20 years later bears out, how much has really changed?

It’s a sorry enough tale to hear that many silent classics no longer exist, regarded only as disposable entertainment and only latterly collected into archives and preserved as valuable film history, but in the case of South Korea even mid and late 20th century films are unavailable thanks to the country’s turbulent political history. Though often listed among the greats of 1960s Korean cinema, Sorrow Even Up in Heaven (저 하늘에도 슬픔이, Jeo Haneuledo Seulpeumi) was presumed lost until a Mandarin subtitled print was discovered in an archive in Taiwan. Now given a full restoration by the Korean Film Archive, Kim’s tale of societal indifference to childhood poverty has finally been returned to its rightful place in cinema history but, as Kim’s own attempt to remake the film 20 years later bears out, how much has really changed?

11 year old Yun-bok has been forced out of his home and into a makeshift hovel near the river thanks to his gambling addicted invalid father’s inability to look after his four now destitute children. Yun-bok likes to narrate his life as a kind of letter to his absent mother who seems to have abandoned the family for unclear reasons possibly related to her husband’s drinking and gambling problem. Attending school as normal in an attempt to work hard and get an education so he can take care of the family in an adult world, Yun-bok, along with his younger sister Sun-na, spends his free time selling sticks of gum in the streets to try and earn enough money to feed everyone before his father drinks and gambles it all away.

Despite his obviously difficult circumstances, Yun-bok remains steadfast in his desire to stick by his family and take care of his siblings. Berated by the teacher for arriving late, Yun-bok finds an ally in a schoolmate who just wants to help even though many of the others shun him because of his raggedy clothes and lice infested hair. Eventually a teacher notices Yun-bok’s distress and urges him to write his struggles in a diary – which he does much as he’d been narrating his days in his imagined conversations with his mother. Moved by Yun-bok’s heartending descriptions of his life on the starvation line, the teacher manages to get the diaries to the newspapers who begin publishing them as a public interest column but just when it looks as if things maybe looking up for the family, Yun-bok loses heart and hops a freight train to look for Sun-na who has run away from home after an argument.

Korea in the 1960s was a difficult place, still bearing the scars of both WWII and the Korean War not to mention the resultant political turmoil. Nevertheless, by 1965 things had begun to pick up as seen in the flip side to Yun-bok’s sorry state of affairs – the various bars and drinking establishments he manages to work his way into in order to sell a few more sticks of gum. These places are filled with the sound of popular music where affluent young couples dance The Twist and salarymen in dark suits cement their business relationships over drinks. For some, everything is going fine but a concerted effort is being made to unsee the kind of unpleasantness which lurks below growing economic prosperity as manifested by 11 year old boys somehow responsible for the maintenance of a family of five.

As one teacher puts it, you can’t break the mirror because you don’t like what you see. Though there are some willing to help Yun-bok (at least to an extent) including his school friend who comes from a well to do family only too glad to set some food aside for Yun-bok and his siblings, out in the real world he finds only other desperate people willing to stoop to theft and violence against a child for nothing more than a few pennies. Many of these episodes are distressing as Yun-bok has his shoeshine kit stolen by an older boy or is violently beaten by a grown man at the harbour but the most serious occurs in the city when he is accused of pickpocketing by some louts who kidnap him and strip him naked for otherwise unclear reasons.

Though Sorrow Even Up in Heaven has a broadly positive ending as Yun-bok’s circumstances seem set to improve thanks to his accidental fame, Kim is quick to point out that there are many Yun-boks out there who can’t all become media sensations. Like many child heroes of classic Korean cinema, Yun-bok remains morally good – the idea of theft occurs to him but he remembers his teacher saying that everything will work out as long as his heart is pure, and his only transgression lies in spending a few pennies on himself to get something to eat and thereby work harder for his family (and for this he pays a heavy price). Even so his circumstances are portrayed in a naturalistic rather than melodramatic fashion neatly undercutting the inherent sentimentality of the material. Though Kim’s approach is closer to neorealism in the early scenes, he mixes in touches of magical realism with the ghostly appearances of Yun-bok’s mother which, alongside impressive montage and superimposition sequences, lend Yun-bok’s story an elevated cinematic quality. Remade several times over the last forty years, Sorrow Even up in Heaven remains sadly timeless in its depiction of an earnest young boy who knows only kindness and honesty even while those around him remain wilfully indifferent or actively cruel in the face of his continued suffering.

Post-war cinema took many forms. In Korea there was initial cause for celebration but, shortly after the end of the Japanese colonial era, Korea went back to war, with itself. While neighbouring countries and much of the world were engaged in rebuilding or reforming their societies, Korea found itself under the corrupt and authoritarian rule of Syngman Rhee who oversaw the traumatic conflict which is technically still ongoing if on an eternal hiatus. Yu Hyun-mok’s masterwork Aimless Bullet (오발탄, Obaltan) takes place eight years after the truce was signed, shortly after mass student demonstrations led to Rhee’s unseating which was followed by a short period of parliamentary democracy under Yun Posun ending with the military coup led by Park Chung-hee and a quarter century of military dictatorship. Of course, Yu could not know what would come but his vision is anything but hopeful. Aimless Bullets all, this is an entire nation left reeling with no signposts to guide the way and no possible destination to hope for. All there is here is tragedy, misery, and inevitable suffering with no possibility of respite.

Post-war cinema took many forms. In Korea there was initial cause for celebration but, shortly after the end of the Japanese colonial era, Korea went back to war, with itself. While neighbouring countries and much of the world were engaged in rebuilding or reforming their societies, Korea found itself under the corrupt and authoritarian rule of Syngman Rhee who oversaw the traumatic conflict which is technically still ongoing if on an eternal hiatus. Yu Hyun-mok’s masterwork Aimless Bullet (오발탄, Obaltan) takes place eight years after the truce was signed, shortly after mass student demonstrations led to Rhee’s unseating which was followed by a short period of parliamentary democracy under Yun Posun ending with the military coup led by Park Chung-hee and a quarter century of military dictatorship. Of course, Yu could not know what would come but his vision is anything but hopeful. Aimless Bullets all, this is an entire nation left reeling with no signposts to guide the way and no possible destination to hope for. All there is here is tragedy, misery, and inevitable suffering with no possibility of respite.

Lee Man-hee was one of the most prolific and high profile filmmakers of Korea’s golden age until his untimely death at the age of 43 in 1975. Like many directors of the era he had his fare share of struggles with the censorship regime enduring more than most when he was arrested for contravention of the code with his 1965 film Seven Female POWs and later decided to shelve an entire project in 1968’s

Lee Man-hee was one of the most prolific and high profile filmmakers of Korea’s golden age until his untimely death at the age of 43 in 1975. Like many directors of the era he had his fare share of struggles with the censorship regime enduring more than most when he was arrested for contravention of the code with his 1965 film Seven Female POWs and later decided to shelve an entire project in 1968’s  Long thought lost, Tuition (수업료, Su-eop-ryo) is an unusual example of Korean film made during the Japanese colonial period. Released in 1940, the film depicts the lives of ordinary people facing hardship during difficult economic conditions though there is no reference made to the ongoing military situation. The story itself is inspired by a prize winning effort by a real life school boy who was doubtless experiencing something similar to the trials of Yeong-dal, however, directors Choi In-gyu and Bang Han-joon made several subversive changes to the script at the filming stage in an attempt to get around the censorship regulations.

Long thought lost, Tuition (수업료, Su-eop-ryo) is an unusual example of Korean film made during the Japanese colonial period. Released in 1940, the film depicts the lives of ordinary people facing hardship during difficult economic conditions though there is no reference made to the ongoing military situation. The story itself is inspired by a prize winning effort by a real life school boy who was doubtless experiencing something similar to the trials of Yeong-dal, however, directors Choi In-gyu and Bang Han-joon made several subversive changes to the script at the filming stage in an attempt to get around the censorship regulations. Though not a big box office hit at the time of its release, Park Kwang-su’s Chilsu and Mansu (칠수와 만수, Chil-su wa Man-su) is not only fondly remembered by its contemporary audience chiefly because of the amusing performances of its still popular leading actors, but is also credited with kicking off what would become known as Korean New Wave. Released in 1988 and set sometime in 1987, this is the new Seoul emerging into democracy after decades of military rule and looking ahead to the glory of the 1988 Seoul olympics. However, as ever, the future has not been evenly distributed and there are those who find themselves unable to climb its ladder through no fault of their own.

Though not a big box office hit at the time of its release, Park Kwang-su’s Chilsu and Mansu (칠수와 만수, Chil-su wa Man-su) is not only fondly remembered by its contemporary audience chiefly because of the amusing performances of its still popular leading actors, but is also credited with kicking off what would become known as Korean New Wave. Released in 1988 and set sometime in 1987, this is the new Seoul emerging into democracy after decades of military rule and looking ahead to the glory of the 1988 Seoul olympics. However, as ever, the future has not been evenly distributed and there are those who find themselves unable to climb its ladder through no fault of their own. Aside from the original 1960 version of The Housemaid (and this perhaps only because of its modern “remake”), mid 20th century Korean Cinema has been severely neglected overseas. Ha Kil-jong’s The March of Fools (바보들의 행진, Babodeul-ui haengjin) is almost unknown abroad but consistently tops Korean lists of the country’s best cinema and has been both enormously influential on later filmmakers and fondly remembered by audiences.

Aside from the original 1960 version of The Housemaid (and this perhaps only because of its modern “remake”), mid 20th century Korean Cinema has been severely neglected overseas. Ha Kil-jong’s The March of Fools (바보들의 행진, Babodeul-ui haengjin) is almost unknown abroad but consistently tops Korean lists of the country’s best cinema and has been both enormously influential on later filmmakers and fondly remembered by audiences. In writing the original novel which inspired Heavenly Homecoming to Stars, Choi In-ho stated that he wanted to tell the story of “a woman whom a city killed”. The novel itself was first serialised in a newspaper where it quickly became a must read and popular discussion point among readers of all ages. It’s perhaps less surprising then that this completely radical film adaptation by first time director Lee Jang-ho proved to be the big cinema hit of 1974. A new “youth culture” movement was beginning inspired by social and political developments from overseas and there was a growing appetite for films and novels which were equally revolutionary. Heavenly Homecoming to Stars managed to provide this but also, crucially, was able to appeal to older age ranges too thanks to its re-imagining of classical melodrama.

In writing the original novel which inspired Heavenly Homecoming to Stars, Choi In-ho stated that he wanted to tell the story of “a woman whom a city killed”. The novel itself was first serialised in a newspaper where it quickly became a must read and popular discussion point among readers of all ages. It’s perhaps less surprising then that this completely radical film adaptation by first time director Lee Jang-ho proved to be the big cinema hit of 1974. A new “youth culture” movement was beginning inspired by social and political developments from overseas and there was a growing appetite for films and novels which were equally revolutionary. Heavenly Homecoming to Stars managed to provide this but also, crucially, was able to appeal to older age ranges too thanks to its re-imagining of classical melodrama.