In the Korea of 1990, a revolution had been fought, won, and then betrayed by its people. Successfully petitioning for democracy, the newly minted Korean electorate went ahead and voted for the chosen successor of the dictator they’d just spent so long trying to oust. Change comes slow, but it comes even if not quite the way you wanted it. Park Kwang-su’s first film Chilsu and Mansu, released in 1988 and set in the contemporary Seoul running to catch up to its Olympic aspirations, had made its own quiet protest about a hypocritical society’s rising social inequality. His follow up, Black Republic (그들도 우리처럼, Keduldo Urichurum), takes a journey back in time while keeping one foot in the present to show us a nation engulfed by a darkness that crushes love, dreams, and possibility all while dangling the shining hope of a better future that seems impossibly far away.

In the Korea of 1990, a revolution had been fought, won, and then betrayed by its people. Successfully petitioning for democracy, the newly minted Korean electorate went ahead and voted for the chosen successor of the dictator they’d just spent so long trying to oust. Change comes slow, but it comes even if not quite the way you wanted it. Park Kwang-su’s first film Chilsu and Mansu, released in 1988 and set in the contemporary Seoul running to catch up to its Olympic aspirations, had made its own quiet protest about a hypocritical society’s rising social inequality. His follow up, Black Republic (그들도 우리처럼, Keduldo Urichurum), takes a journey back in time while keeping one foot in the present to show us a nation engulfed by a darkness that crushes love, dreams, and possibility all while dangling the shining hope of a better future that seems impossibly far away.

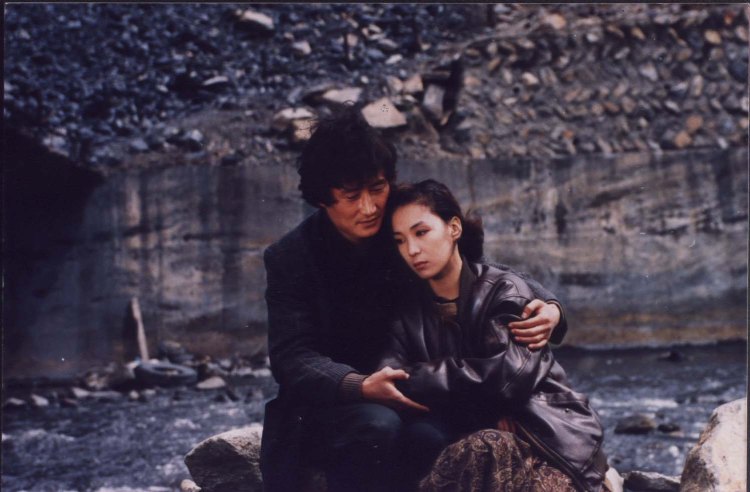

Tae-hun (Moon Sung-keun), a student protestor wanted by the police, heads into the mountains under an assumed name hoping to get a job in a mine. However, this is a period of intense economic volatility and the mining industry is collapsing. When his attempts to find work as a miner fail, Tae-hun (going under the name Gi-yeong) overhears a conversation in a cafe and manages to get a job in a local briquette factory.

Park opens in darkness as Tae-hun makes a phone call to his mother in which he never speaks and she reassures him that everything will be OK while the sound of a train gradually gathers in the background. When Tae-hun arrives at his destination, he finds himself in a barren, blackened land where everything is quite literally falling apart. The mines are closing and the landscape, desolate as it is, is peppered with derelict buildings and the modest, makeshift homes of the rural poor at the constant mercy of their greedy masters. As a newcomer, Tae-hun is not privy to the town’s secrets, but quickly comes to understand that though he may have escaped Seoul, the struggle is inescapable, because the struggle is Korea. The owner of the briquette factory is also some kind of loanshark involved in a suspiciously close arrangement with the local mine owner who is in the middle of a labour dispute with the miners who are petitioning for fair pay and better conditions. Haunted by the memories of his protest days, Tae-hun finds himself looking on at another candlelight procession calling for workers rights but rendered impotent, forced to remain silent or risk attracting the attention of the police.

Meanwhile, Tae-hun’s silence sees him unwittingly pulled into the orbit of those he would usually oppose. Seong-cheol (Park Joong-hoon), the illegitimate son of the factory boss, takes his own sense of crushing impossibility out on the entire town. Technically the “vice-president” of the factory, Seong-cheol is a sometime enforcer for his father’s greedy loan sharking business and thinks nothing of striding in and helping himself to the petty cash to spend on women and booze while gazing at the photo of his long absent mother. An invitation to dine with Seong-cheol and pals brings Tae-hun into contact with melancholy sex worker Yeong-sook (Shim Hye-Jin) who begins to fall for him when he skips out on her after Seong-cheol has pulled one of his usual tricks in giving her away in an attempt to buy friendship through influence.

Like Tae-hun, Yeong-sook is also trapped, running, and living under an assumed identity. Through her exposure to Tae-hun who is, after all, so different from the other men in the mountains, she begins to rediscover a sense of hope and possibility. Yeong-sook quits the illegal part of her job as a “coffee girl” and deepens her bond with Tae-hun through nursing him after he is arrested and beaten by the police who seem to harbour an innate suspicion towards him despite little evidence, but their love will require another act of faith and flight and the world in which they live may not let them to escape.

Everyone here is trapped, lying to themselves or others, wishing things were different than they are but has long since given up the hope they ever could be. While Tae-hun attempts to ride out the storm by burying his head in the coal dust, feeling it fill his lungs, struggling to breathe, Seong-cheol opposes his order with chaos, laying waste to half the town in a self destructive venting of his rage and resentment towards his selfish, unfeeling father, and a society he feels has already rejected him. Impossibility and hopelessness are the defining qualities of this world of corruption and exploitation in which there can be no escape or salvation, only crushing futility. Park closes with an ironic coda of swapped fates and tragic promise which places Tae-hun right where he was when we first met him, defeated by hope but still in motion, if for an uncertain direction.

Black Republic was screened as part of the Korean Cultural Centre’s Korean Film Nights 2018: Rebels With a Cause screening series. It is also available to stream online via the Korean Film Archive’s YouTube Channel.

Following on from the

Following on from the  Lee Byung-hun stars as a conflicted high school teacher who begins to see echoes of a woman he loved and lost years ago in a male student.

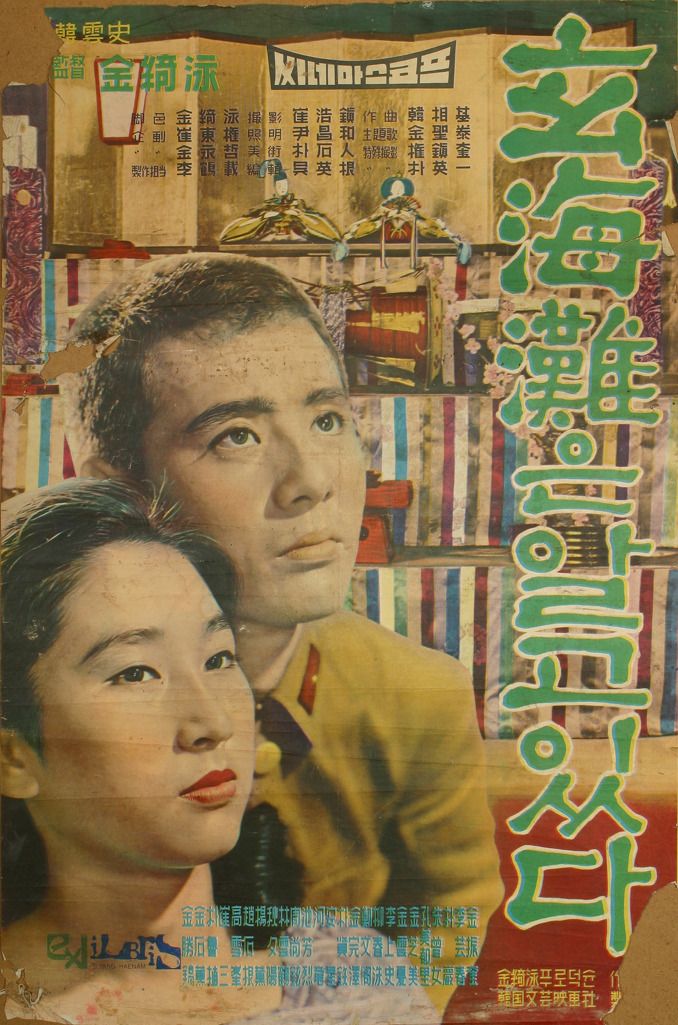

Lee Byung-hun stars as a conflicted high school teacher who begins to see echoes of a woman he loved and lost years ago in a male student. Kim Ki-young recasts the folly of war as a romantic melodrama in which a Korean conscript to the Japanese army receives harsh treatment from his sadistic superior but later falls in love with a Japanese woman.

Kim Ki-young recasts the folly of war as a romantic melodrama in which a Korean conscript to the Japanese army receives harsh treatment from his sadistic superior but later falls in love with a Japanese woman. Moon Jeong-suk stars as a determined young woman hellbent on becoming a judge in defiance of social convention which views marriage and motherhood as the only paths to female success. Encouraged by her father but forced to dodge her mother’s constant attempts to marry her off, she pursues her dream in spite of intense disapproval.

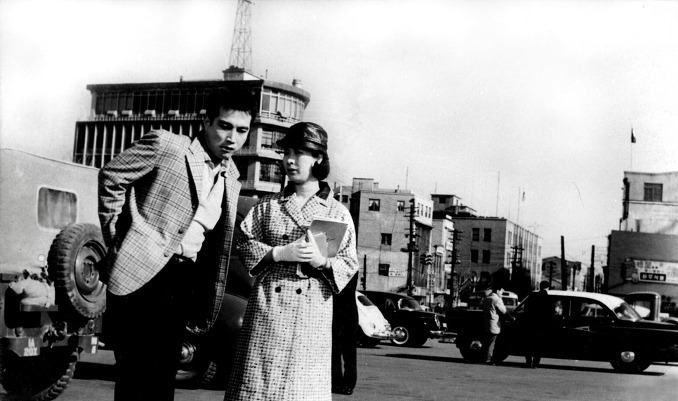

Moon Jeong-suk stars as a determined young woman hellbent on becoming a judge in defiance of social convention which views marriage and motherhood as the only paths to female success. Encouraged by her father but forced to dodge her mother’s constant attempts to marry her off, she pursues her dream in spite of intense disapproval. Kim Ki-duk (the old one!) draws inspiration from Ko Nakahira’s Dorodarake no Junjo for a tragic tale of love across the class divide as poor boy Du-su (Shin Seong-il) and Ambassador’s daughter Johanna (Um Aeng-ran) meet by chance and fall in love. Faced with the impossibility of their “pure” love in an “impure world” the pair find themselves an impasse, unable to reconcile their true feelings with the demands of the society in which they live.

Kim Ki-duk (the old one!) draws inspiration from Ko Nakahira’s Dorodarake no Junjo for a tragic tale of love across the class divide as poor boy Du-su (Shin Seong-il) and Ambassador’s daughter Johanna (Um Aeng-ran) meet by chance and fall in love. Faced with the impossibility of their “pure” love in an “impure world” the pair find themselves an impasse, unable to reconcile their true feelings with the demands of the society in which they live.  Im Kwon-taek’s “artistic breakthrough” stars Ahn Sung-ki as a young man who has abandoned his girlfriend and university studies to become a Buddhist monk but later meets an older man who indulges all of life’s Earthly pleasures such as wine and women.

Im Kwon-taek’s “artistic breakthrough” stars Ahn Sung-ki as a young man who has abandoned his girlfriend and university studies to become a Buddhist monk but later meets an older man who indulges all of life’s Earthly pleasures such as wine and women.

After a brief pause, the

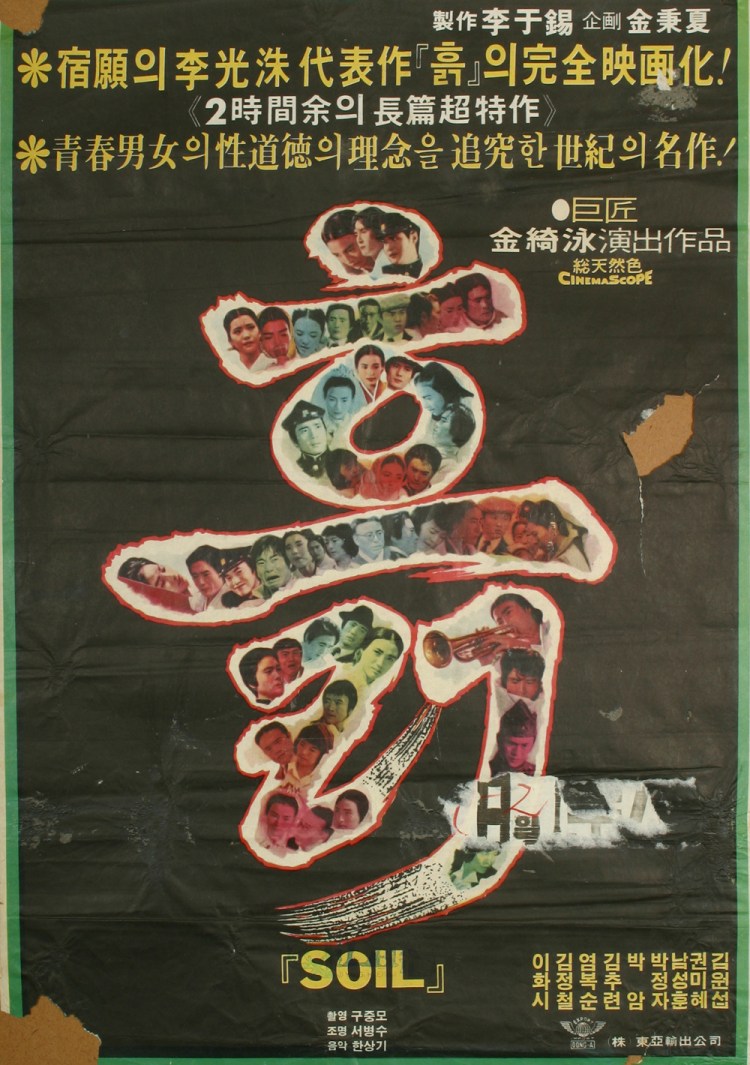

After a brief pause, the  Housemaid director Kim Ki-young adapts Yi Kwang-su’s 1932 novel of resistance in which a poor boy studies law in Seoul and marries the daughter of the landowner he once served only to decide to return and help his home village suffering under Japanese oppression.

Housemaid director Kim Ki-young adapts Yi Kwang-su’s 1932 novel of resistance in which a poor boy studies law in Seoul and marries the daughter of the landowner he once served only to decide to return and help his home village suffering under Japanese oppression.

Directed by Chung Ji-young, White Badge adapts Anh Junghyo’s autobiographical Vietnam novel in which a traumatised writer (played by Ahn Sung-ki) is forced to address his wartime past when an old comrade comes back into his life.

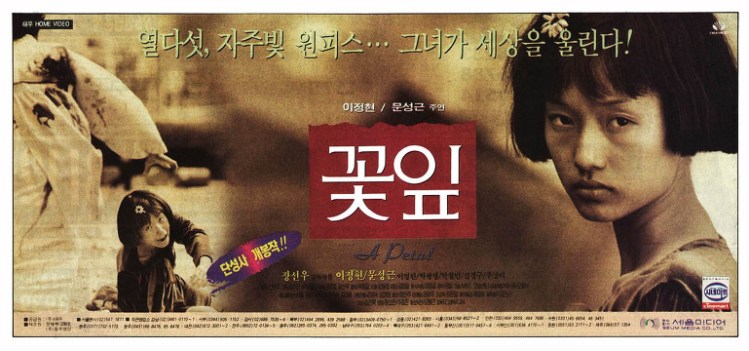

Directed by Chung Ji-young, White Badge adapts Anh Junghyo’s autobiographical Vietnam novel in which a traumatised writer (played by Ahn Sung-ki) is forced to address his wartime past when an old comrade comes back into his life. Adapting the novel by Choe Yun, Jang Sun-woo examines the legacy of the Gwangju Massacre through the story of a little girl who refuses to leave the side of a vulgar and violent man no matter how poorly he treats her.

Adapting the novel by Choe Yun, Jang Sun-woo examines the legacy of the Gwangju Massacre through the story of a little girl who refuses to leave the side of a vulgar and violent man no matter how poorly he treats her. Adapted from a novel by writer and activist Hwang Sok-young, Im Sang-soo’s The Old Garden follows an activist released from prison after 17 years who cannot forget the memory of a woman who helped him when he was a fugitive in the mountains.

Adapted from a novel by writer and activist Hwang Sok-young, Im Sang-soo’s The Old Garden follows an activist released from prison after 17 years who cannot forget the memory of a woman who helped him when he was a fugitive in the mountains. The debut feature from Kim Sung-je, the Unfair is an adaptation of Son Aram’s courtroom thriller which draws inspiration from the Yongsan Tragedy in which residents protesting redevelopment were forcibly evicted and several lives were lost including one of a police officer.

The debut feature from Kim Sung-je, the Unfair is an adaptation of Son Aram’s courtroom thriller which draws inspiration from the Yongsan Tragedy in which residents protesting redevelopment were forcibly evicted and several lives were lost including one of a police officer. An adaptation of the novel by Kim Ae-ran who will also be present for a Q&A, E J-yong’s My Brilliant Life stars Gang Dong-won and Song Hye-kyo as teenage parents raising a son who turns out to have a rare genetic condition which causes rapid ageing.

An adaptation of the novel by Kim Ae-ran who will also be present for a Q&A, E J-yong’s My Brilliant Life stars Gang Dong-won and Song Hye-kyo as teenage parents raising a son who turns out to have a rare genetic condition which causes rapid ageing.